Meditation practice is not something we do for ourselves alone. Because of the nature of interdependence, this practice has the power to enter our lives as a collective – building a container of awareness that allows us to distinguish between the conditioned wants and fears of ego and the deeper movements of intuition that come from the heart and lead to right action. For me, meditation practice led me out of my comfort zone and into a Borneo rainforest inhabited by an indigenous tribe.

For years, I have been meditating on the edge of creeping industry, in places where the forest was eroding as the industrial world encroached. Living amongst trees and rivers, birds and lizards, I felt a deep sorrow at their impending loss, and when I visited urban areas, felt the absence of them as though I were missing an essential nutrient. I wondered: Does anyone else even notice this is missing? This deep grief became conscious through meditation and careful tending. It had been underground for most of my life, like a dark river that ran into me through my indigenous, forest-dwelling ancestors. It was this feeling — fully felt in meditation to the point of heartbreak — that brought me to Muara Tae village in Borneo to meet the Dayak Benuaq people, whose ancestral forest is being bulldozed by palm oil companies.

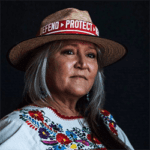

In February, I visited the village with my friend, Ambrosius Ruwindrijarto (Ruwi) who won Asia’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize for his work on behalf of indigenous people. It felt as though we were visiting the site of our collective tuberculosis, and I wanted to offer to the tribe what little I had: my presence and shared sadness over this profound loss. But when we got there, I was shocked at what I found. The devastation was just as bad as I feared: dry, parched land, freshly cleared of forest and planted with rows of scrubby little palm trees. But here was the shock: The people I met were determined, undefeated after so much defeat, continuing to act out of love for the forest like a healthy immune system. Living with a deep sense of purpose and a mandate that for them went back to the beginning of time, tribal leaders made it clear that they would work to protect this forest to the last tree. This, they said, was why humans were put here: to nurture and protect the balance of life on earth.

Those of us living in the industrial world may not know of this village or others like it, but we are intimately connected to them. The trees that are fast being clear cut supply our oxygen, as the rainforest of Indonesia is the earth’s Eastern lung, second only in size to the Amazon. Our supplies of packaged cookies, cleaning products and organic microwave popcorn come from the palm oil now growing where the forest used to be. And our desire for the latest model smartphone or laptop requires ever more precious metals, and so companies scrambling for new sources of gold want to dig right under Muara Tae village to find it. For this tribe, sitting on a gold mine isn’t something to celebrate.

Since Western-style negotiations have failed to stop the bulldozers, tribal leaders told us that their best hope is to conduct an ancient vow ceremony — a powerful method of conflict resolution that is only used when their very survival is threatened, and so is taken with life and death seriousness. In the past, it has averted direct confrontations and even war. This 64-day process, which [began] at the end of April, 2014, has much to teach all of us in the West about actively becoming conscious of our contributions to collective conflicts; harnessing the power of our intention when a situation looks impossible; remembering the long view that includes our ancestors, descendants and larger cosmic forces; and aligning ourselves wholeheartedly with what is good not just for ourselves personally, but for the whole of life.

Meditation always presents the subtle temptation to float above it all in a peaceful space rather than build our capacity to take in difficult truths and feel difficult feelings. For the privileged Westerner, this tendency is reinforced by the protection of comfortable lifestyles far from the ravages that those on the front lines are living with right now. And so I invite you to bring your practice to the earth by joining me, Ruwi, and the Dayak Benuaq people in a rare and powerful cultural exchange. As they perform the ceremony, Ruwi and I will be on the ground, asking questions, taking pictures, and reporting back on their methods and wisdom. You will get an intimate glimpse into the ceremonial world of this remote tribe, and be offered the opportunity to ask questions of the elders and shamans, inquiring across paradigms so that we can search together for creative, meditative approaches to what appear to be impossible collective problems.

The paradigm we live in — the one that makes bulldozers and mines — right now seems opposed to the indigenous way and the survival of the forests, but it doesn’t have to be. A creative, meditative inquiry into integrating the best of these world views holds great promise for the future of our forests and all who depend on them.

This article was originally published on the Huffington Post website, and is generously shared here. To learn more, visit flamingseed.com. You can sign up for the flamingseed blog and newsletter to receive regular updates including photos, wisdom from the Dayak elders, and suggestions for meditations and inquires that are in alignment with what the Dayak are doing. You can also receive updates at the Guardians of the Forest Facebook page.