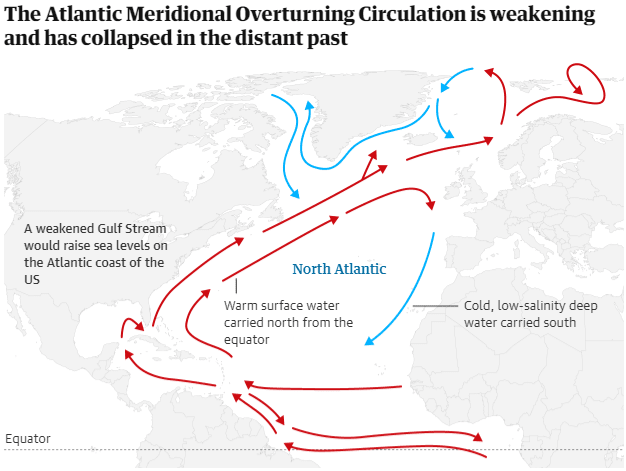

A recent report published in the journal Science Advances offers insight into the potential catastrophic effects of the collapse of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), a complex current that drives warm water north from the equator toward Iceland and Western Europe before drawing cold water back down from the polar region toward northwestern Africa and South America. The circulation acts as a great temperature regulator, and if it stops, the global climate could quickly be thrown into chaos.

Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, described it well in a conversation hosted by The New York Times in 2022:

For example, what we are now showing is that when the Greenland ice sheet, which is one tipping element system, melts very fast, it releases cold, fresh water into the North Atlantic. This slows down another tipping element, the AMOC, the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, which has slowed down by 15 per cent, is a thermodynamic engine, which is driven by really heavy saline water that flows from the southern ocean at the surface, releases heat up in the Gulf Stream, and then sinks to the bottom and flows back and it circulates in the North Atlantic. But with fresh water, it dilutes the weight, the density goes down, the engine slows down, and the whole overturning slows down. That pushes the monsoon system further to the south, impacting another tipping element, the Amazon. The Amazon basin gets less rainfall, more draughts, more fire, releases carbon, and comes closer to its tipping point. But it also locks surface water, heavy saline surface water, in the Southern Ocean, which can explain why the Western Artic Ice Sheet, another tipping element, is melting faster than science predicted.

Rockström admits later in the talk that he and other scientists are not always the best communicators. And that is okay. It is not their job to communicate these truths to the masses. That is a job that falls on others, including journalists. Part of our work is to listen to leading thinkers, understand their warnings, and to clearly communicate them in ways our readers can understand.

For this, we might lean on writers and moviemakers for help. Some of us will have seen the 2004 film The Day After Tomorrow, which offers a dramatic glimpse into what a collapse of the AMOC might entail: a new ice age over much of the northern hemisphere. According to the paper in Science Advances, sea surface temperatures could see “differences as large as 10°C near Western Europe.” (Science Advances) And since the sea water temperatures act to moderate the air in the winter, temperatures in the British Isles, Iceland, western France, and beyond could see dramatic, even politically destabilizing changes. While it may not quite be as dramatic as The Day After Tomorrow, it offers a potential wake-up call for all of us.

In another film, The Perfect Storm (2000), based on the book by Sebastian Junger, we find a microcosm of our current situation: the warnings, the hubris, the uncertainty, and ultimately a fateful decision. The story unfolds with gripping detail, painting a vivid picture of the precarious existence of a crew of ordinary, hard-working Americans as they navigate the treacherous waters of the Grand Banks. At the helm is Captain Billy Tyne, a seasoned seaman with a deep respect for the sea but also plagued by the relentless pressures of a dwindling catch and mounting debts.

As the crew of the Andrea Gail set out on what seems like just another routine fishing expedition, they are blissfully unaware of the looming threat that awaits them on the horizon. But nature, unfathomable in its complexity, has other plans. A convergence of weather systems, including a hurricane and a powerful nor’easter, creates the perfect storm.

In the face of such overwhelming forces, the crew of the Andrea Gail find themselves humbled by their own insignificance in the vastness of the ocean. Despite their skill and experience, they are no match for the overwhelming power crashing on them from the sky above and the sea below. As the storm intensifies and the waves grow higher, they find themselves at the mercy of forces beyond their control.

The story is riveting, and it is one that much of humanity might be living through more in the coming years. It is hard to imagine, given Europe’s place as a destination for refugees for many decades, but what if millions of Europeans needed to flee their homes, left uninhabitable by seismic shifts in temperature? And if the Amazon burns, what about those who depend on the region’s water and croplands? No doubt, the rest of the world will see changes as well, and these could come far too quickly for mitigation.

As we reflect on the story of the Andrea Gail, we are reminded of the humility with which we must approach the natural world, recognizing our own vulnerability in the face of its awesome power. Like those fishermen, we know of the potential dangers—an ever-growing number of warnings from climate scientists ensure this knowledge is widespread. And like them, we are pushing forward with far too little done to ensure our safety. In the wake of catastrophic events such as the real-life tragedy of the Andrea Gail and the broader existential threat posed by climate change, humanity finds itself at a pivotal moment.

Buddhism teaches us to confront suffering with wisdom and compassion, recognizing the interconnectedness of all beings and the impermanent nature of existence. In the face of the climate crisis, this perspective offers valuable insights into how we can navigate these turbulent times with resilience and grace. Too often, we forget our interconnectedness. We look at those facing tragedy as “others” about whom we can forget. Sometimes, malicious leaders even stoke this sentiment, causing us to turn away from those in need.

Are there societal structures in place that drive individuals and groups to harm the environment, to turn a blind eye toward our coming demise, just to make their living? What wisdom could a bodhisattva bring to this perilous moment?

What wisdom could a bodhisattva have brought to the crew of the Andrea Gail? What skillful means might have been used to persuade the crew to stay home, to give up their quest for consumption and wealth—for them perhaps just a catch to earn the money they needed to pay their bills? Are there societal structures in place that drive individuals and groups to harm the environment, to turn a blind eye toward our coming demise, just to make their living? What wisdom could a bodhisattva bring to this perilous moment?

The crew of the Andrea Gail relied on one another for support and survival, recognizing their interconnectedness. But by then they had been cut off from the many people on land who could best help them. Will we break off into isolated groups, left on our own to fight for survival? What world are we creating for future generations? Our actions—or inaction—in response to the climate crisis have far-reaching consequences, affecting not only ourselves but all living beings on Earth.

The story of the Andrea Gail serves as a sobering reminder of the consequences of hubris and heedless disregard for the forces of nature. Similarly, our unsustainable exploitation of natural resources and our disregard for the ecological limits of the planet have brought us to the brink of environmental collapse. To avert disaster, we must heed the lessons of the past and chart a new course towards ecological sustainability and social justice.

The latest report on tipping points should spur all of us to do more, in whatever spheres we are able, to avoid going over the edge. There is hope in the rise of green energy, electrification, solar wind power, and more. But the pace of these developments is still not enough yet to slow down the growth of carbon fuel burning in the world.

Solutions must come quickly, say the scientists. And we would add that they must not be made at the expense of the poor, the disenfranchised, and the marginalized, but instead be for the mutual benefit of all beings.

This article was originally published on Buddhistdoor Global. It is reprinted here with permission.