The Priority of Profit

The well-known saying of Jesus, “The sabbath was made for man, not man for the sabbath,” might be reformulated with regard to the economy: “The economy should serve the needs of people; people should not be made to serve the economy.” Yet the logic of modern corporate capitalism often dictates just the opposite, that people be subordinated to the demands of the economy, an omnivorous giant that feeds off a steady stream of human sweat, blood, and tears.

With the profit motive as its driving vector, the mammoth corporation directs all the components of its complex operational system toward profit maximization. When profits stagnate or decline, the company may freely adopt whatever measures are needed to change course and push earnings back on an upward curve, often without regard for the physical well-being of its employees. While labor unions earlier formed a bulwark against exploitation, the decline of unions has given corporations license to get their way without fear of resistance.

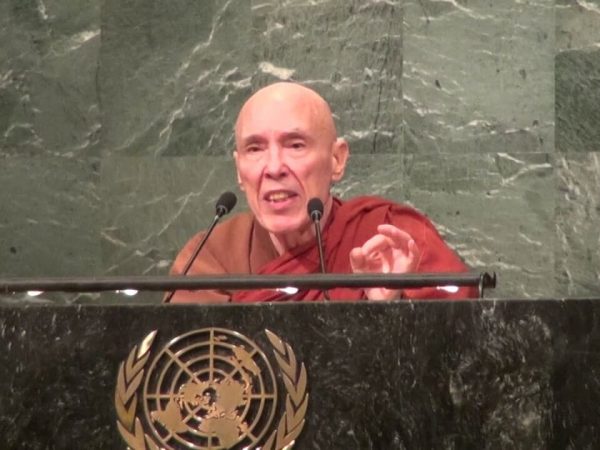

A particularly egregious example of this inversion of ethical priorities1In session three of the second EcoSattva Training, Bhikkhu Bodhi presented his updated and more comprehensive analysis of the domains, actualization and perversion of value. Even the PDF handout Domains of Value is compelling. came to light just last week when President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act to compel meat-processing facilities to resume operations. In March and April, these plants had become hot spots for Covid-19. By the end of last month, at least twenty workers had died from the disease and over 5,000 were infected. Since then even more workers have been infected and died, but a shortage of testing equipment prevents us from knowing the exact numbers.

An unspoken premise behind the injunction is a judgment that black and brown lives—the lives of the workers—are of less value than the lives of the owners and managers and thus may be sacrificed to ensure the plants remain operative.

As infections spread, state and local authorities used their power to order some of the most badly contaminated plants to close, a measure considered necessary to protect public health. In sum, during those two months, thirteen meatpacking and food-processing plants shut down, including some of the nation’s biggest. In response, the executives of the giant meat corporations mounted a campaign of opposition, claiming that the closing of the meat plants would endanger the national food supply. John Tyson, chairman of the board of Tyson Foods, the world’s second largest meat processor, published a full-page ad in major newspapers, including the New York Times, warning that “the food supply chain is breaking.”

This message got through to the president, who invoked the Defense Protection Act to demand that the plants reopen. The DPA was originally adopted to grant the federal government the authority to order private industries to produce materials and equipment needed in times of war. But Trump used it, not for national defense against a hostile military power, but to protect the meat industry from declining profits. The president’s executive order states that the closure of meat-processing plants by state and local authorities has been “undermining critical infrastructure during the national emergency,” and he called on the Secretary of Agriculture to “take all appropriate action… to ensure that meat and poultry processors continue operations consistent with the guidance for their operations jointly issued by the CDC and OSHA,” that is, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Whose Lives Matter?

For ‘essential workers’ it’s ‘get back to work’ and ‘voluntary’ guidelines at pandemic hot spots. For a CEO class that’s white and wealthy it’s profits and legal liability protections.

Trump’s decree puts in jeopardy not only the workers themselves, but their families and communities. Meat-processing workers often live in multigenerational households with scant opportunity for quarantine or social distancing. In such tightly cramped quarters, if a younger worker becomes infected with the virus, even if they remain asymptomatic, they might easily infect other members of the household; for older relatives infection may prove fatal. But for the president, such concerns are subordinate to those about the meat supply. In the words of Stuart Appelbaum, president of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union: “We only wish that this administration cared as much about the lives of working people as it does about meat, pork and poultry products.”

Despite the rhetoric of “critical infrastructure” and a “national emergency,” a continuous supply of meat is in no way essential to meeting our country’s nutritional needs. Our obsession with meat may actually be harmful to our health. While reduced availability of meat might agonize those who crave the taste of beef, pork, and chicken, it’s not going to undermine their health. The demand to reopen the meatpacking plants is driven primarily by the wish to guarantee that profits from the sale of meat continue to flow into the coffers of the food corporations, sustaining the salaries of executives and the dividends of shareholders. The costs will be borne by those forced to return to work, who will be sacrificing their health and even their lives on the altar of the plant. To step into a processing plant at a time when many workers are carrying the virus, untested and undetected, is to place at risk one’s health and even one’s life.

The demand for the continued operation of the plants forces the workers to choose between their jobs and their lives—a terrifying choice that no one should ever have to face.

Adding to the tension between management and the workforce, between capital and labor, is an underlying racial and ethnic dynamic. A large number of workers in the meat-processing industry are Latinos, Asians, and African Americans; many are immigrants or members of immigrant families. Thus the demand that the plants be reopened, and that workers return to their jobs, suggests that an unspoken premise behind the injunction is a judgment that black and brown lives—the lives of the workers—are of less value than the lives of the owners and managers and thus may be sacrificed to ensure the plants remain operative. In the words of Frank Sharry, executive director of the immigrant organization America’s Voice: “Trump sees business owners as his people and he sees a diverse group of workers as expendable…. For ‘essential workers’ it’s ‘get back to work’ and ‘voluntary’ guidelines at pandemic hot spots. For a CEO class that’s white and wealthy it’s profits and legal liability protections.”

What the workers want and need is access to the federal stockpile of masks and other protective gear, daily testing, enforced physical distancing, and full paid sick leave during periods of illness. When protective equipment at the plants is in short supply, it’s hardly surprising that workers fear losing the most precious possession they have, their own life. As one local organizer in Iowa told Amy Goodman of Democracy Now!:

I have family working across the board, across the state and into some other states, in the industry. So, you know, it’s very scary for my family, my immediate family, my extended family. I have cousins who now have tested positive because of these plants. My sister and her husband have tested positive here just recently because of these plants. And again, [we’re] just incredibly scared.

Who does the government represent—ordinary people or the moneyed interests that contribute to campaigns and flood Congress with lobbyists?

The president’s executive order does nothing to allay these fears. It does not make the protective guidelines mandatory, but instead shields the meat companies from legal liability in cases of workplace exposure to the virus. Any company legally challenged can claim that, in reopening during the pandemic, it was merely following a decree issued by the highest authority in the land.

The demand for the continued operation of the plants forces the workers to choose between their jobs and their lives—a terrifying choice that no one should ever have to face. If, from fear of contracting the virus, workers stay back from work, they may well lose their jobs and the income they need to support themselves and their families. If, to maintain their household, they report to work, they risk contracting the virus and losing their lives.

A Crisis of American Democracy

The perilous choice faced by workers in the meat industry represents, in microcosm, the crisis in American democracy, pointing to the big question too often hidden behind discussions of everyday social issues: Who does the government represent—ordinary people or the moneyed interests that contribute to campaigns and flood Congress with lobbyists?

The answer, which is obvious, underscores the need for a radical overhaul of the economic paradigm that currently reigns, that of corporate capitalism grounded upon an ideology of free market fundamentalism. In the ultimate analysis, to preserve our political democracy, we must institute economic democracy, transitioning to a system that gives workers fuller control over their terms of employment. But such changes are long-term goals. In the short term, with a pandemic raging that has already taken more American lives than the Vietnam war, what is needed is a slate of workplace regulations, rigorously enforced, that ensures workers remain safe at their jobs.

Moral Responsibilities to Planet and People

It would certainly be desirable, too, if meat were to be knocked from its place as the centerpiece of the standard American diet in favor of plant-based sources of protein. Apart from its cruel treatment of billions of helpless animals and the merciless death it inflicts at the slaughterhouses, livestock cultivation is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and a leading cause of deforestation, water and air pollution, and biodiversity loss. Raising animals for food requires vast amounts of land, water, and grain, a deplorable waste of food in a world where chronic hunger afflicts close to a billion people. Further, high intake of red meat and processed meats is linked to heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and premature death. Thus a nation-wide shift from a meat-based diet to a plant-based diet would bring manifold benefits. To forestall unemployment, under a federal program workers in the meat industry could be retrained to take up more benign types of livelihood.

Companies will seek to cut corners whenever they can get away with it. It thus becomes the obligation of the government to step into the fray and come to the defense of the workers.

Nevertheless, such a pivotal change in the American diet is unlikely to be realized anytime in the near future, and we must therefore focus on protecting the welfare of workers in their present occupation. This requires both ethical commitments and regulatory enforcement. A company must fulfill its moral responsibility to the well-being of its workforce, ensuring that its employees do not jeopardize their health and well-being at the workplace. A company that treats its workers as disposable, as mere instruments of production whose lives can be imperiled to serve the company’s interest, has transgressed against a basic principle of workplace ethics.

Yet, in face of the moral recklessness of modern corporate capitalism, the need for regulatory protection is particularly acute. Almost invariably, companies will seek to cut corners whenever they can get away with it. It thus becomes the obligation of the government to step into the fray and come to the defense of the workers, which means that the government must enact laws that safeguard workers and impose regulations that prevent industries from operating in ways that endanger their workforce.

A government that does not protect workers from the ruthless demands of industry has forfeited its responsibility to the people it purportedly represents. Despite their professed good intentions, industries can’t be fully trusted to regulate themselves. Regulation is the job of the government, a job that must be rigorously pursued to protect the well-being of the workers. It is only in this way that we can move, gradually, toward becoming a nation that gives everyone the chance to flourish.

References

- 1In session three of the second EcoSattva Training, Bhikkhu Bodhi presented his updated and more comprehensive analysis of the domains, actualization and perversion of value. Even the PDF handout Domains of Value is compelling.