I turn 50 tomorrow. I can’t say I imagined turning 50 in the middle of lockdown three, with strict ‘stay at home’ measures still in place here in England, the global Covid-19 pandemic spreading more slowly and now busily mutating. I’m also relieved there will be no chance of surprise birthday parties, and time to continue reflecting before spring bursts. In what has been an extraordinary year for all—with some suffering way more than others, and nearly two and a half million people already dead from Covid-19—I count my blessings as I begin, with some excitement, a new decade, a new half century.

The world feels strangely smaller and other-than-human species feel closer by.

There’s been a whole lot of the traditional Buddhist ‘four sights’ buffeting and shaping my life this year: old age, sickness, death and the ‘holy teacher/ascetic’—most likely, yours, too. I am blessed to sit frequently, albeit virtually, week in, week out, with Dharma teachers, with sangha. This helps me to stay present, this call to sit, to breathe, to get up again and to engage as we witness the certainty we thought we knew crumbling around us.

A very recent health scare has also made me appreciate this body and this life, here-now, in the words of Tsongkhapa:

The human body, at peace with itself,

is more precious than the rarest gem.

I have noticed more acutely than ever in the past few weeks when this particular body isn’t at peace with itself. Given that the spread of Covid-19 unites us globally, I find myself empathising with friends, family, and folk I’ll never meet across the continents, wondering how things are. The world feels strangely smaller and other-than-human species feel closer by. As I type finches feed at the window feeder, passers by stopping to smile and listen to their full-bellied chirruping. Maybe staying home has given us a chance to realise we’re not the only species, perhaps with more silence to notice birdsong and even the roaming of wilder creatures nearer to the edges of the wild, even in our built environments. Maybe the chance to notice this body’s co-existence with the planetary body.

I flinch when I notice adverts for foreign travel, or, last night, reading the newsletter of a much-loved local botanical garden and a feature entitled, ‘Missing your holiday dreams?’ The article recounts the author’s South African travels, ending, ‘Roll on the next adventures!’ I, too, love adventures. The flinching is in response to the ‘business as normal’ narratives desperately trying to re-instate themselves, without time to reflect, digest, and start to learn from this pandemic. There is so much to learn. Meanwhile, the holiday companies seduce us with sun-drenched adverts of white sand, far flung beaches—anything to distract our minds from the here-now.

Of course, I’m as guilty as anyone in doing distraction. I don’t necessarily think it’s a bad thing, consciously planned distraction; a little boxset ‘zombie’ time. What feels more pronouncedly zombie-like is un-knitted up thinking. The flinching when I read the botanical garden’s newsletter article. The garden folk do amazing work ensuring the survival of thousands of rare and threatened native plants, educate us about different species, care deeply about the biosphere, and then feature an article on international tourism without a mention of the impact of human behaviour on the biosphere; no climate emergency, no sixth extinction catastrophe, no loss of biodiversity mentioned. Not a carbon footprint in sight.

The flinching is in response to the ‘business as normal’ narratives desperately trying to re-instate themselves, without time to reflect, digest, and start to learn from this pandemic. There is so much to learn.

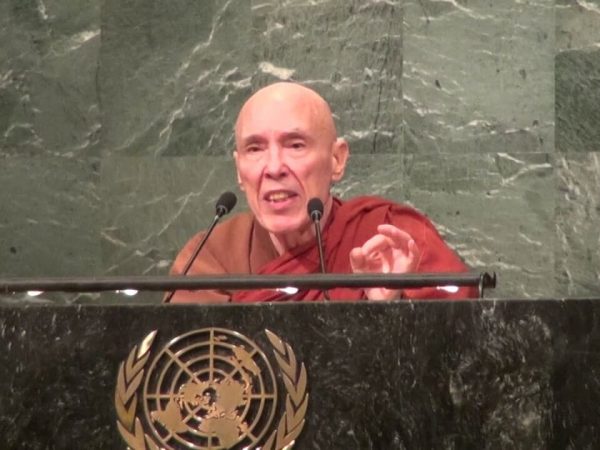

The same is often true of Buddhist pilgrimages to the traditional sites associated with Gautama Buddha of Bodhgaya, Kushinagar, Lumbini, and Sarnath. In a recent Tricycle article ‘The Climate Threat to Buddhism’s Holy Sites’ Eliza Rockefeller explores how climate change’s disproportionate impact on South Asia will affect the Buddhist pilgrimages ‘circuit’. Whilst she quotes the Venerable Metteyya Sakyaputta saying visitors should be aware of their, “impact on these fragile places” and make, “mindful choices”, for example, using ethical travel agents, hotels, and the like, there is no mention of the environmental impacts of pilgrimage travel. There is no linking up of the awareness of Dharma practice; actions having consequences etcetera with the phenomena of climate change and the effect on the holy sites (a sadly missed opportunity for a direct, timely Dharma teaching, too). In the article Rockefeller says how, on his deathbed, the Buddha told his followers to visit the sites, as reported in the Dīgha Nikāya. What would the Buddha say now, 2,500 years later, in the throes of a global pandemic?

Mulling the botanical garden newsletter and the Tricycle article reminds me of my decision, 17 years ago, to stop flying with the earth in mind (I wrote about it here). It reminds me how that decision has, at times, hurt, in a going forth sort of way: the friends and family I haven’t visited, the teaching and conference presentation opportunities I’ve turned down, the places I would love to see again—I would be straight back to the Rift valley and other parts of sub-Saharan Africa, where I was once an aid worker.

I recall what not flying has taught me: to slow down, to see, head-on, the capitalist conditioning that, in not flying, has challenged my ‘right’ to jump on a airplane just because I have the money in the bank. It has taught me that my body staying more local doesn’t mean my body-mind can’t travel and expand, non-locality being one of my current favourite subjects—stretching my body-mind to pinging point! It has shown me how unpopular and counter-cultural it is to take an action as ‘drastic’ as not flying (I honestly see it as neither drastic nor radical, and there’s way more I need to do to be less oil dependent.)

Will our human bodies be at peace with themselves, now that inequality has been highlighted so vividly, in how we treat the planet and how we treat one

another?

I’m obviously not suggesting everyone stops flying. I am suggesting that we connect with what we love about living in planet earth and embodying the precepts of living from loving kindness and living simply. Remembering we are nature, nature is us, and living from that basis. It is becoming pretty clear that we need to wean ourselves off our oil addiction, individually and collectively, and, for some, travel maybe a good place to start. I’ve never much been drawn to pilgrimage to the ancient Buddhist sites. This might be because part my own heritage is part ex-colonial, part local to South Asia—a complex combination—so perhaps that shapes my decision. Although I do understand the need to make a pilgrimage. Visiting my grandfather’s world war two grave on the Oslo Fjord—travelling overland—was one such pilgrimage I needed to make, and I know friends who have had profound experiences visiting Bodhgaya.

Of course, for some sangha friends, struggling to make the rent or buy enough food, pilgrimages to the ancient Buddhist sites are a red herring. Those of us practising Buddhism in the ‘Global North’ need to be aware of the level of privilege pilgrimages entail and see how open and accessible our sanghas—spiritual communities—are to those who wish to follow a path of awareness, regardless of their income, or colour, or class. Covid-19, too, has highlighted these inequalities in no uncertain terms: the woeful underfunding of our National Health System (the NHS we’re still fortunate to have here in the UK), how the pandemic has taken its toll much more dramatically in areas where years of austerity have left people disempowered and impoverished. Let’s do everything within our powers, as we live through this pandemic, to remember that we love in an interconnected world (I meant to type live, but let’s keep it as ‘love’). Will our human bodies be at peace with themselves, now that inequality has been highlighted so vividly, in how we treat the planet and how we treat one another? What can we do, knowing life is fleeting and precarious? Treading lightly on this precious planet, respecting the lives of all that lives, may we carry on adventuring.