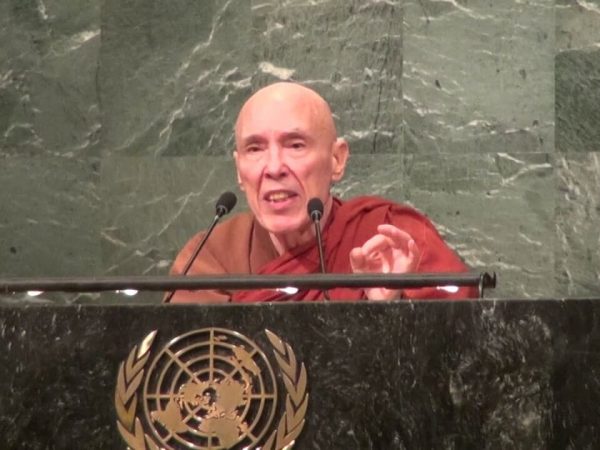

Ecobuddhism: In your book, “The Wisdom of Sustainability”, you describe consumerism as a “demonic religion”. Consumerism is one of the main drivers of the climate crisis. Why and how can it be described from a Buddhist point of view as a demonic religion?

Greed and hatred go together. People want more and more, and if they don’t get it, violence takes place. But underneath everything is delusion.

Sulak Sivaraksa: From the Buddhist point of view, the three root causes of suffering are greed, hatred and delusion. Consumerism promotes greed. Greed now dominates global society, through advertising in the media and because transnational corporations are in control. It is linked with hatred and violence. Violence is on the whole controlled by politicians, but more politicians are now under the control of transnational corporations. So greed is now in control of hatred.

Greed and hatred go together. People want more and more, and if they don’t get it, violence takes place. But underneath everything is delusion. People on the whole don’t know who they are – they aspire for more power, money and luxury, whatever. These are the three root causes of our suffering.

I think we Buddhists should not simply preach. We should concretize it. That’s why I keep saying consumerism is an expression of greed. Most governments—even democracies, not to mention dictatorships—promote hatred. But deep down it is delusion. Delusion is directly linked with mainstream education, which teaches people how to be clever, and promotes greed and hatred. Mainstream education never teaches people to know who they are. They don’t teach how to breathe properly—the basis is always “cogito ergo sum”—one-dimensional thinking.

If people are taught to breathe properly and mindfully, we can tackle greed, hatred and delusion. That’s why His Holiness the Dalai Lama is such an important example. He is a simple monk who gets up every morning, breathing properly. You can see his wisdom and compassion shining. At the same time he realizes that is not enough. It is a good foundation, but we must learn from science too, and bring it together with wisdom and compassion. Scientific know-how without proper breathing, wisdom & compassion, becomes a servant of transnational corporations and governments. We must come together now to change ourselves—and also change this world.

The more you promote violence in the media, the more people feel insufficient. Hence consumerism: they will buy this and buy that in order to get happiness. They never do get it, but they carry on aspiring for it. Violence is a threat. It creates fear in a population. People hope that by acquiring something, they will overcome the threat. But you can never overcome a general state of insecurity.

False Selves, Fictional Persons

EB: Social psychologist Clive Hamilton wrote a powerful book called “Requiem for a Species”. He describes the “consumer self”—a false self that is continually dissatisfied and seeks to establish its identity through buying more goods. Cycles of dissatisfaction, anxiety and debt are created as it tries to acquire more elements of consumer identity. Meanwhile, the judicial position of transnational corporations now gives them legal rights of “personhood”.

SS: To be protected.

EB: When corporate behaviours are examined using psychiatric criteria, we discover an institution with some kind of psychopathic personality.

SS: That’s right.

EB: Some people say “We must not condemn corporations, because there are also human beings working there.” Yet if the institution of the corporation is a psychopathic institution, its CEOs serve an ideology that has no empathy. Can we Buddhists afford to be sentimental about this?

We must fully do our best—not out of self-concern, but for the next seven generations, and for all species.

SS: No, but if our condemnation comes out of anger, that will not help. We would do better to understand and de-structure these corporations. My main concern is social structure that is unjust and violent. Corporations are the biggest and most powerful examples.

Most churches, and even the Buddhist Sangha, also have structures that are violent. We cannot ignore that issue. We may talk of “the future of Buddhism”, but if we don’t tackle social structure, it is mere chatter. To tackle this issue seriously, we have to learn who we are. We re-structure ourselves first, so that we don’t campaign for ego, for victory or for Buddhism.

Humility, compassion and wisdom are necessary to tackle social structures that are violent and unjust. With that in mind, we do need social scientists, anthropologists and mainstream scientists to come together. That is the new possibility. We have to push ahead with it.

EB: So Buddhist analysis in your view has to prioritize understanding of cultural and structural violence—which are less easy to discern than violent colonialism, because they hide themselves in a kind of mental fog. In order to discern the fog, one has to de-structure it within oneself.

Humility, compassion and wisdom are necessary to tackle social structures that are violent and unjust.

SS: Precisely. And let’s remember, Gandhi’s success was also his failure. He used truth and nonviolence against oppressors outside India – the British empire. But he never used Satyagraha (the power of truth and nonviolence) against the unjust social structure within India—the four varnas (Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra castes).

Ambedkar (who led thousands of the Dalit “untouchable” people to Buddhism) was great because he emerged from beneath the four varnas. Unless that system is tackled, India will remain un-liberated. 60 years after independence, the social structure is still awful. They got rid of one imperialism, but now they blindly follow American neo-imperialism. The suffering of India’s poor carries on and on.

This is why more and more so-called “untouchable” people become Buddhist. I am happy to talk with them. I say “You became Buddhists, that’s great. But if you still hate the Brahmins, that doesn’t help. You must learn to cultivate compassion and wisdom, and how to change the social structure—rather than hating the Brahmin oppressor.

Never Too Late to Change

EB: In America now we see a non-violent struggle confronting the corruption of the political process by Big Oil corporations.

If people are taught to breathe properly and mindfully, we can tackle greed, hatred and delusion.

SS: That’s great. More and more people are awakening there, and even breathing more correctly! They are learning to question smartness and arrogance. We remain young at heart if we learn to be humble, breathe properly and honour others. I see much in America to be hopeful about. It is a country that has done dreadful things in the last 100 years or so, but it’s not too late to change.

I was involved with the creation of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship there. Many wonderful Americans have become Buddhist. Most are well-to-do and white, and they may not have embraced lifestyle changes that fully reflect the Four Noble Truths. But I think there are real developments. It is a matter of urgency, after all. The world may be irreversibly damaged by climate change during this decade.

EB: The great danger identified by James Hansen and colleagues (at NASA) is that unless there is a sufficiently rapid change in the energy system—unless we successfully turn back the power of the fossil fuel industry—humanity will lose control of the process. That brings us back to the “demonic” nature of consumerism and corporations.

SS: Precisely.

EB: Simon Baron-Cohen at Cambridge University has identified an empathy circuit of 10 interconnected regions in the human brain. It is underactive in psychopathic individuals who commit acts of cruelty. Such a person does not feel the normal, involuntary human reaction of empathy for others’ feelings. A genetic lesion affects the empathy circuit. We instinctively call unfeeling cruelty “evil”. Baron-Cohen defines it on a neurological-genetic level. “Evil” is the “zero-empathy negative” state.

Now what happens when fossil fuels create the greatest profits in human economic history, but are controlled by zero-empathy negative institutions? In 1995, evolutionary geneticist Edward Wilson asked “Is Humanity Suicidal?” Sixteen years later, carbon emissions are out of control and extreme weather events have become “normal”.

SS: We have been uprooted from our own culture. 150 years ago when we opened the country, westerners complained that they could not ride horses, so we built new roads. Now we have so many roads and cars that the natural drainage (of Bangkok) has been lost.

We have abandoned our traditional respect for Mother Earth, Mother River and Father Mountain. Now we see them only as material to be consumed, turned into money and subject to technology. We have to pull ourselves back to our roots, while at the same time being open to new scientific knowledge. We must change ourselves and society fundamentally, through non-violent action.

To be mindful one must cultivate inner peace. But we must also have kalyanamitra, good friends who have good ideas, with whom we can dialogue. They need not only be Buddhists, they could be Christians or atheists. This isn’t a matter of numbers. A few friends can achieve a lot with technological know-how, commitment, less egoism, more compassion and wisdom.

Time is short and pressing. But with groups of people like this, we may pull through. Even if we don’t pull through, we will have done our best. We must fully do our best—not out of self-concern, but for the next seven generations, and for all species.

We all have Buddha nature. It is my conviction we can pull through. I strongly support creative civil disobedience. It is wonderful! We have to use all kinds of tactics. We have to learn to be non-violent. We have to learn to be mindful.

Do the best you can, but don’t expect to win.

This article was originally published on Ecobuddhism.org on December 11, 2011. It is reprinted here with permission.