“For more than 30 years, the science has been crystal clear,” sixteen-year-old Greta Thunberg courageously argued at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City in September of 2019. “How dare you look away and say that you are doing enough!” Warning that global carbon emissions are currently on track to exceed the Paris Accords’ aspiration for a 1.5-degree Celsius net gain in less than nine years, she raged, “How dare you pretend that this can be solved with business as usual?” With righteous anger, she proclaimed, “You are betraying us . . . If you choose to fail us, then I say, ‘We will never forgive you.’”

What would it look like if we decided to live and act in a manner that future generations would forgive? On behalf of what kind of earth would this new mode of living and acting emerge?

Certainly, these questions indict us temporally. The ecological crisis manifests the locking in of our past carbon exuberance—we are experiencing climate as history—and our present actions demonstrate flagrant disregard for any sense of intergenerational justice. We act as if what matters of life begins and ends with us. We have no relationship or obligations to the past or the future. This indictment has a clear temporal vertical axis (the past manifesting as present ecological disruptions and present actions damning the future as catastrophic amplifying feedback loops emerge as we cross tipping point after tipping point). It also has a clear horizontal spatial axis. All of human life is at stake and much of global civilization has been indicted. We will find a response together or we will perish together. If we opt for the latter, we should also remember that those who have least contributed to the emergency are most likely to be the ones disproportionately harmed by it. This not only includes the poor and marginalized, but also the many nonhuman lifeforms with whom we share the earth.

Questions at the Heart of Our Practice

Although I think that we can defensibly expect any thoughtful person anywhere in the world to take these questions seriously, perhaps even as the greatest ethical challenge of our time, these are also serious issues for Buddhist practice. But it is not enough merely to apply Buddhist practices to the problem. We need to dig deeper to appreciate that the current ecological crisis reveals that these questions belong to the heart of our practice. As the ecological crisis rages and each day presents grimmer and grimmer news, we can begin to appreciate that realizing our “original face” is not only a personal awakening. It is an awakening to our Buddha nature as through and through ecological. This is not a Buddhist approach or response to the increasingly catastrophic ecological crisis as if we can approach it from the outside.

To practice the self is to realize the myriad beings and to realize the myriad beings is to realize the self.

Rather, we are these ecologies in their splendor and pain. In the spirit of Dōgen’s Genjō Kōan, we could say that to study the Way is indeed to study the self and to study the self is to forget the self and awaken to the emptiness of the self as our shared being with all of the causes and conditions, including all of the lifeforms, great and small, that help comprise our being, just as we help comprise their being. If we are these relations, we are as good as these relations. To study the self is to care always for these relations, especially when they are clearly showing us the ugly news of who we are and what we are becoming.

For these reasons, I do not think that Buddhist practice can or should be regarded simply as a personal practice, although it is certainly the case that no one can do your practice for you and that you should exert your entire being toward it. The awakening of the Way is also an awakening to our ecological and social relations. To care for them is to care for the self and to care for the self is care for them. They are not simply two. Today we need to learn to articulate this relationship in the glaring light of the Anthropocene, the current epoch defined by human impact on the Earth’s geology and ecosystems.

Although there are many great teachers, ancient and contemporary, I am moved to take as my companions and teachers the great poet, philosopher, eco-activist, and Rinzai Zen practitioner Gary Snyder (b. 1930), and the great Kamakura period Elder of Sōtō Zen, Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253). I regard the ongoing ecological crisis as what Snyder called “this time of New World Disorder.” The disorder is not simply the default position of the individual monkey mind, as it often was in early forms of Buddha Dharma, but rather the monkey mind has now become a global mind, and the ecological crisis, along with its non-dual intertwining with other global disorders such as economic inequality, the resurgence of authoritarian governments and cultures, etc., vividly displays this disorder. This calls not only for personal awakening to the causes and conditions that comprise who we are—care for all beings—but also for a global awakening.

The turn to Snyder’s writing as well as Dōgen’s exceptionally poetic mode of Zen discourse, or whomever one finds inspiring in this respect, need not be an attempt to chart the development of their respective ideas or to elaborate every facet of their thinking and writing. Rather it can be a meditation that seeks to read, think and practice along with both of them in a manner that is mindful of the place from where one reads them today. It becomes a meditation that seeks to express something of the place from which Snyder and Dōgen practice, think, and write.

This allows one to attend, for want of a better word, to the spiritual dimension of what Dōgen called the “Great Earth” and its relationship to our prevailing ecological crisis. This spiritual dimension is currently endangered, that is, it is becoming harder and harder even to appreciate the spiritual as a problem or question. The “spiritual” seems increasingly irrelevant to anything that matters, but given our current sorrowful state of human habitation, never has it been more urgent. I confess, however, that I struggle with a word like spiritual, which has become so broadly applied so as to mean little, if anything; it has a long and philosophically dubious history, a history that often reinforces the kind of thinking that I am trying to get beyond; it often proposes an otherworldly perspective when the problem is that we have not been present to the earth; it often vaguely expresses a dissatisfaction with the prevailing institutional forms of religion, while hoping, somehow, some way, to satiate the needs that traditional religion seems to have betrayed; and it is often a disavowal of the rigor and intelligence, as well as the compassion and the wisdom, that the current ecological crisis demands. I urge using this word cautiously and temporarily as a sort of down payment on a more nuanced manner of speaking to this dimension of the problem: the current crisis is not so much a failure of rationality, but a symptom of the poverty of our practice. We—and by that I mean both humans and the earth with its myriad forms of shared life—are as good as our practice.

Practice of the Wild

Such a practice can take some of its inspiration from what Dōgen calls the realization of the “Great Earth” and what Snyder calls the “practice of the wild,” comprised of the play of waters and mountains, emptiness and form. We are of this play and it forms us dynamically even as we realize it. We are not studying objects that are foreign to us, or that surround our putative atomistic self as its “environment.” To practice the self is to realize the myriad beings and to realize the myriad beings is to realize the self.

The earth itself is a sūtra and should be studied and engaged as an element of our practice.

The practice of the wild also invites us to think non-dualistically about the relationship of human culture to its enabling ecologies. This is not to collapse the distinction between culture and the wild, but it is to insist that, in distinguishing culture from the wild, we are not separating or detaching it. The problem with culture is not that it is culture, but rather that culture has lost the sense and practice of its bioregional mooring. Culture, as it often was in Neolithic cultures as well as indigenous cultures, and as it is often being radically reclaimed and reborn in the latter, is an expression of the wild and our ongoing symbiotic relationship with it. As Glen Sean Coulthard, in his provocative work Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, articulates it: indigenous place was experienced as “grounded normativity” that was “deeply informed by what the land as system of reciprocal relations and obligations can teach us about living our lives in relation to one another and the natural world in non-dominating and non-exploitative terms.”

This realization also helps us to think non-dualistically about our practices as well as the cultural artifacts of the wisdom traditions to which we turn. What it might mean to address the Great Earth with painting, the poetic word, and sūtras? The language that addresses the Great Earth is composed of the same wild and elemental forces as the Great Earth itself. Both are in their own way expressions of what the Mahāyāna tradition calls “skillful means” (upāya). A “true teaching has no particular shape” Dōgen tells us. “The entire phenomenal universe and the empty sky are not but a painting,” as he also tells us in the fascicle (Gabyō or The Painting of a Rice Cake) that Snyder places as the epigram to his brilliant and deeply Buddhist poetic magnum opus, forty years in the writing, Mountains and Rivers without End.

In one of his most rightly celebrated fascicles, Sansuikyō (Mountains and Waters Sūtra), Dōgen writes of mountains and waters, which were subject to an East Asian approach to painting that depicted mountains with waters running through them and forming watersheds with humans realizing themselves as existing as a small part within this play. Dōgen extends this practice beyond the cultural artifice of mountains and waters to include the sūtra as actual mountains and waters. The earth itself is a sūtra and should be studied and engaged as an element of our practice. As Snyder reflected, “Now it becomes possible for contemporary environmentalists, of wide and compassionate view, also to think of Dōgen as a kind of ecologist. An ecologist, not just a Buddhist priest who had a deep sensibility for nature, but a proto-ecologist, a thinker who had remarkable insight deep into the way that wild nature works.” Buddhist writings can express the ecological relations that comprise the cultures and practices from which they gain their intelligibility.

This being said, it is important not to think of the Great Earth with no beings and places left out in merely generic terms. It is also the singular interrelated forms of life that comprise us as what we might call an EcoSangha. In these times of political and ecological turmoil, it is important to reclaim this place as something like Turtle Island. The latter is the name, following its coinage by Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy, but now used widely, including by many indigenous peoples and their allies, for a reawakening to the places that we currently occupy as North America. Snyder tells us that contemporary “people live on it without knowing what it is or where they are. They live on it literally like invaders.” Practice can seek to “discover” Turtle Island, that is, attempt to remove some of the obfuscation of imperial ideology. I regard the practice of endeavoring to cleanse the mind of ideological toxins as a necessary part of any serious Buddhist practice. We do this bioregion by bioregion.

Engagement with Politics

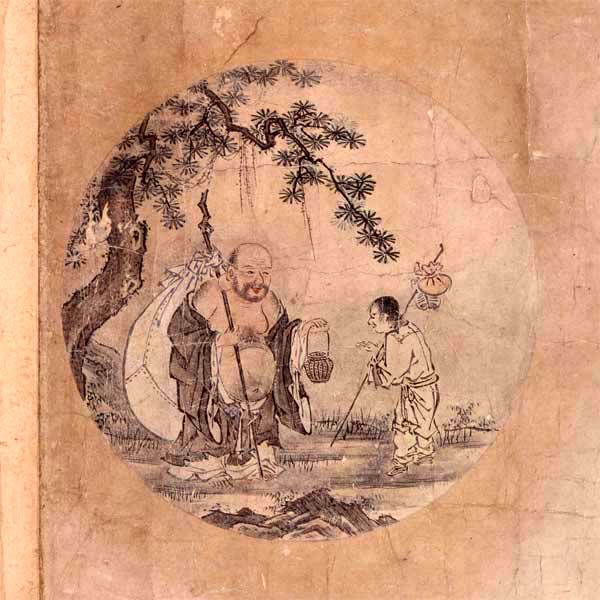

Finally, we cannot have a practice that is apolitical, as if the dusty marketplace of politics merely sullied an otherwise pure practice. The culmination of practice, as the final of the Ten Oxherding pictures and poems dramatically illustrates, is always a return to and deep engagement with this market. We have to ask ourselves about the kinds of political arrangements that are sensitive and responsive to the needs of our bioregions and that help them flourish. From this perspective, we must confess that politics and economics as usual has been an ecological (as well as ethical) catastrophe.

We cannot have a practice that is apolitical, as if the dusty marketplace of politics merely sullied an otherwise pure practice.

Perhaps the time has come to consider how to grow the Dharma seeds of our intrinsically ecological practice. (It has always been ecological, but the contemporary ecological crisis now foregrounds this aspect.) Perhaps the maturation of these seeds includes the practice of something that we might provisionally (and poetically) call earth democracy. This is to cultivate the practices of our politics and economics in a manner grounded in the value of all forms of life, not just human life. Such a practice would be impossible without first cultivating a practice of peace. Reflecting on his work with the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, Snyder stated in 1985 that “it’s part of our mission . . . as Buddhists to extend the concern for peace outside the human realm to the nonhuman realm.” This is not some Pollyannaish fantasy that one day the lamb really will lie down with the lion and that all creatures will transcend conflict, including the most conflict-addicted creature of all, we humans. As Snyder often reflects, nature has its dark and cruel aspects.

Cultivating peace also does not mean that one is always successful at achieving it or maintaining it. Moreover, peace is not the same thing as pacification, a well-practiced weapon of war and domination in which we dominate the dynamic cultural imagination as well as the multiplicity of other beings, both of which comprise the great earth sangha as vital and free. It is rather a question of ahimsā—non-violence in the sense of doing “the least possible harm in every situation,” to avoid or oppose hiṃsā, injury, harm, violence. This is what Snyder also simply calls “respect for all beings.” It is not the pipe dream of the end of all conflict; it is rather a practice of the wild—a term that for Snyder names not randomness and chaos, but rather self-generating natural processes—that issues from an ongoing awakening that is shaped by wisdom and compassion, these mountains and rivers within and without that are without end.

Moreover, earth democracy is not practiced in a vague “save the world” sort of a way. It is practiced bioregion by bioregion, sangha by sangha, and it reveals that Buddhist practice also carries the demand that one discover and clarify and appreciate the bioregion, watersheds and all, that is the greater Sangha within which we all practice, each in our own way.

The Dharma name that ODA Sessō Rōshi gave Snyder was Chōfū, “Listen to the Wind,” or “Listen, Wind.” The kanji fū 風, literally, wind, also connotes the inexpressible as well as customs and cultural practices. In the compound fūdo, for example, it is the inexpressible qualities of do, land, that give rise to its customs, practices, and lifeforms. Snyder spent his life trying, as we all do, to live up to the challenge of his Dharma name, to hear “without fear” the otherwise obscure inexpressible qualities of our time and place. That, too, can be the hope of our practice, what we bring to the innumerable sentient beings that we vow to liberate.

This article was originally published by Insight Journal, Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. It is reprinted here with permission.