I’d like to talk about something tonight that, usually, if I talked about it at all on a group retreat, I would probably choose to do it at the end, maybe the talk on the last evening as you’re moving back into the world – the other world. But for different reasons, we’ve decided to do it now, for various reasons. And then some of it we’ll just leave and just put it there now, and some of the themes I’ll pick up later on.

I’m going to start with a question for you. Where do you think all this is leading? Where do you think it’s going? What’s your sense of that? What’s your fantasy of that? And ‘fantasy’ there is a good word. It’s not a bad word. We need fantasy. We need a fantasy of practice. It’s very important. What’s your fantasy, what’s your sense, where is it going?

Some people will be familiar from hearing or reading, there is the idea of awakening or liberation. Some people may not have heard those terms before, or may have heard it but don’t really relate to that. So whether I do relate to that kind of idea, wakening/liberation, something like that, or whether I don’t, whether I’m a practitioner of many years, or whether I’ve just come very new to practice, what’s the sense of where this is leading? Am I aware of my fantasy of where practice is headed? We usually don’t think this way too consciously, but to me it’s very important to be conscious what’s going on there – not because it’s a bad thing and I shouldn’t have one. I should have one. I need to have one; otherwise I can’t motivate myself. But to be aware of it. So do I, for instance, somehow dimly or more consciously imagine that when I’m awakened, or more awakened, or further on down the line, everything will be easier? It will be much more calm? Everything will be simpler? The world and its complications will be simpler to my eyes? Do I expect that? Do I want that?

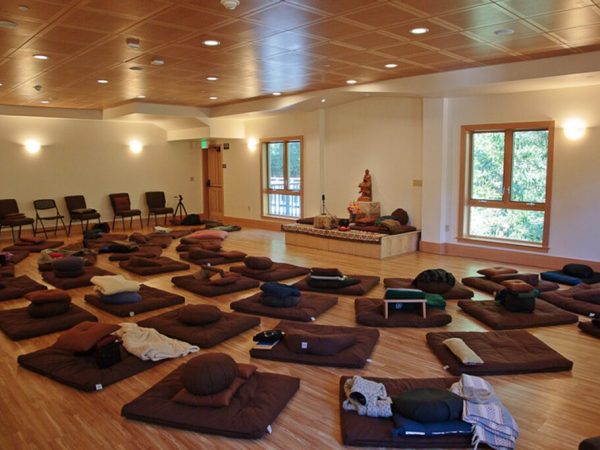

Buddha. Buddharūpa, Buddha statue, which you can get at a lot of garden centres and things nowadays. [laughter] What does it say to you? It’s a really powerful image. It’s an archetype already – not quite as much in our culture as the Crucifixion, but it’s there in our culture, by the fact that you can get it in a garden store. People know what that is. What’s it saying? What does it say? What’s it communicating? What’s that archetype communicating? What’s he doing? What does it show him doing? He’s sitting there, very serene, very still, very undisturbed, oftentimes with his eyes closed in meditation. That’s a powerful archetypal image that’s being communicated there.

I think what practice can offer is this capacity and courage to hold and respond to the world’s pain.

Through the image, a lot else gets communicated. He is the archetype or an archetype of the equanimous sage, the sage, the wise one, equanimous through his sagacity, through his wisdom. But there’s a kind of aloofness in it. Very much, if you read the ancient texts, there is an aloofness, a transcendence of the world that’s very much there in the original texts. We don’t like that so much nowadays, so we kind of paper it over to fit more of our contemporary view. But it’s still communicating something about an equanimity that comes out of a certain kind of wisdom, that has a kind of aloofness in it, separation, distance.

So not good, not bad, but it has an effect. Compare the story of Jesus overturning the tables of the moneylenders, this hot-headed young man in the temple. It’s a different archetype being communicated. Not good, not bad, just different and has different effects. You can say, “I don’t even think about these archetypes,” but they permeate the culture, and the meditation culture, and the spiritual culture, etc., and it has its effect. It most certainly has its effect, even for people who are new and don’t think about things like liberation, etc.

Why is this important? Because the fantasy that I have in relationship to practice will determine kind of what my practice becomes. It determines the direction of my practice. It can’t not have an effect there. It might also be that I choose the fantasy and the archetypes that I’m relating to dependent on what I want. So I might want less bother, less impingement, less hassle, less disturbance, less agitation, and so I zero in on the spiritual archetypes or whatever that seem to communicate that and seem to suggest the possibility of that, to both.

A little while ago I was talking to a good friend, and she was saying when she was growing up as a child and into her adolescence she felt the visceral pain, looking around her in the world, at the pollution that one can be aware of – the plastic in the oceans, the plastic in the environment, all kinds of things. She actually felt a real pain with that. As she got a little older and encountered the possibility of learning meditation and Buddhism and all that, the thought was, “If I practise, maybe that pain will die down. I’ll have some freedom from that pain.” But that’s not what happened. Actually an increase in sensitivity, an increase in sensitivity with deepening practice. The heart opens, and it comes with that price – alongside a kind of equanimity, but the sensitivity is growing.

Now, in the Buddha’s time, 2,500-and-something years ago, the whole fabric of the society and the culture was different. Couldn’t have conceived that the human population would grow so exponentially, and the rapidity of technology, technological innovation, etc., industrialization. They couldn’t have conceived that humanity would be able to have such a devastating effect on the climate. Just didn’t enter into. Couldn’t have conceived of the kind of juggernaut of globalization that is now full steam ahead. Just wasn’t in the picture. Very small society, me and the acts that I do, and the immediate consequences of that. When you have globalization, it’s a much more complex picture. Where did this come from, this shirt? What effect does it have on someone in Bangladesh or something?

So what does all that mean? It’s a very different situation we’re dealing with now than before. What do I imagine as I move towards awakening (if I think of those words or not)? That everything will become, appear easier, feel easier, appear simpler, more calm – everything calms? Some things – and I’m only where I am, so I’m going to share from my experience – some things, yes, most definitely: much more calm, much more ease, much more simplicity. Some things, yes. Some dukkha, some areas of suffering, just gone, “cut off” in the Buddha’s [words]. They’re “cut off at the root.” They can’t come up again. Absolutely.

But given all that complexity, some situations and some sufferings that we are in the midst of in our life and in our culture and our society, global society nowadays, answers are not so easy. Whole situation not so easy, not so easy at all. Then the question is: am I willing to be uncomfortable? How willing am I to open to that discomfort, this being, this heart and mind? Am I willing to actually bear all that and have that kind of vulnerability? What do I want? Is it my own private nirvāṇa (if you think in nirvāṇic terms, which many people don’t)? Or maybe, again, I don’t think in terms of nirvāṇa; I just have an image that as I grow in practice and hopefully develop, maybe I have this distant image that someday my heart will be touched by this stuff but not really disturbed. I’ll have a kind of soft, openheart, which is nice – it’s nice to have that – but there’s not a sense of deep disturbing.

Some of you probably know this novel, Franny and Zooey, by J. D. Salinger. Do you know this? It’s a really fabulous, wonderful novel. They’re sister and brother. Franny is the sister and Zooey is the brother. They’re talking, and Zooey is in his thirties, I think, and he has an ulcer, so Franny is asking him about his ulcer. When his sister asks him about his ulcer, he says:

Yes, I have an ulcer, for Chrissake. This is Kaliyuga, buddy, the Iron Age. Anybody over sixteen without an ulcer’s a goddam [sic] spy.”1J. D. Salinger, Franny and Zooey [Kindle edn] (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1955).

That’s typical J. D. Salinger language, but you get the point. I was at a party – I don’t know when; two weeks ago or something – and I was talking with a friend of a friend. She made a very insightful comment. She’s not a Dharma practitioner, but just to preface it a little bit, Buddhism, the Dharma talks about suffering and the end of suffering. That’s the thread through all Dharma teachings – everything is suffering and the end of suffering. It’s a very famous comment of the Buddha, “I teach suffering and the end of suffering.”2e.g. in SN 22:86 and SN 44:2. But what does that mean, ‘suffering’? What does ‘suffering’ mean? Nowadays, it has a ton of different interpretations. What did the Buddha mean when he said ‘suffering’? What do I mean when I say ‘suffering’? What do you mean when you say ‘suffering’? And what do you mean when you say ‘the end of suffering’?

This woman at the party – I thought it was really insightful – she said, well, historically in the West, if you go back to Freud and this idea that we need to open the awareness to the depths of the psyche, to the intrapsychic, and the suffering that can come from that, and understand that, and relate to that. Then a little while, when a little time goes by, and psychoanalysts and psychologists, etc., understand that actually the family influence is really important. So for Freud it was all here – one was projecting onto the family, but the problem was really here. A few decades go by, and the problem – now bigger understanding – the problem comes from the family, from stuff that happened in childhood. Nowadays, it’s almost unheard of – you don’t meet anyone who doesn’t acknowledge that there’s some suffering that comes from that. We all think, “My childhood, my parents, were like this and this and this,” and it’s understood I need to work with that, I need to explore that, I need to heal that. So there’s been this growth of the understanding, which you never encounter in the Buddha. He never talks about someone had a painful childhood or their parents were difficult. It just wasn’t there in the understanding. Nowadays, we wouldn’t think twice about it. Maybe some people now are beginning to consider, say, the influence – slightly wider – of gender and race, maybe a little bit. But what about one step further, and the society, and the environment, and the suffering that comes to me from that? You understand? The whole picture is getting bigger and bigger. There’s a growth in understanding here.

What am I modelling as a Dharma teacher? Am I modelling a kind of nice security of fitting nicely in as a well-respected citizen … Am I modelling that? Well-adapted, well-trained, well-tamed?

So Freud talked about the repressed – what am I repressing that can come up and cause me pain? But it’s a hundred-and-something years later now. We all know about this childhood pain. It’s very important. But is that really where the repressed is these days? Is that what we’re repressing nowadays in the culture, or is it something in a whole other area? Don’t know; that’s just a question. But I think that’s part of it. The social and environmental situation affects us, and we affect it. Just as we know that it’s helpful to explore family wounds, childhood wounds and all that, and heal that, so also with the social/environmental pain. With all that, some agitation with practice gets less, and I feel some agitation gets more, I feel, or it certainly can.

The same friend was talking about many retreats done in Bodh Gaya, the place of the Buddha’s enlightenment and the monastery there where there are retreats in Bihar, which is, I think, just about the poorest state in India. The suffering there is in your face – children, and beggars, and incredible poverty, and lack of hygiene, and malnutrition, and disease. It’s just in your face while you’re practising meditation in the retreat. Very different than the environment we have here. For her, it was really helpful. It gave a real perspective on one’s own pain and one’s own suffering. Not to dismiss that pain, not at all to dismiss it, but to give it a perspective. That was actually helpful. She said, looking back, there were some people it was too overwhelming, perhaps. It was just too overwhelming, and they kept it at arm’s length, and tried to make a cocoon where it’s not touched. She could see the consequences over years, that that cocooning can have real consequences.

So it’s interesting now for me – there’s a revolution. Dharma practice is a kind of revolution, sometimes people say. And the revolution is learning to turn inside, and not chase so much in the world, and not all the time go out and run away from one’s experience, but turning to be with one’s difficulty, one’s emotions, etc. That’s really true and really important. But again, there are so many double-edged swords in life and in practice, and one of them can be the danger that Dharma practice can itself become a little insular, a little self-obsessed even, perhaps. Or that one is compassionate with others, but only with certain kinds of pain, interestingly, that one can kind of relate to a little bit. I’m not saying this does happen; I’m just saying it’s a potential shadow side, a danger that we need to look out for.

If I’m in a relationship with someone, a friendship or a family person or a lover or spouse or whatever, and there’s difficulty and there’s pain, then it’s not only always that I let go of it here [inside oneself], and I look inside, and I let go, and I work with the emotions as we’re doing. Sometimes I need to communicate something, and I need to act. I need to do something. I would say it’s the same with what impinges on us in terms of social/environmental difficulty. It’s not just here, even; I need to speak out. I need to act. So revolution is turning in, and revolution is turning out.

So I threw out this question at some point: what do we want from working with the emotions? What do we want? And I actually said we can make a list here. We can add things to our list as we go through this retreat, and we already threw a few things out. For me, it feels really important that also what we’re doing is developing the courage and the capacity to feel the pain of our times. Sometimes as a teacher, that’s, I feel, what’s in the back of my mind when I – I’m very interested in people meeting their individual suffering, which is why we’re doing the practices that we’re doing, and teaching mettā, and this and that, and what’s so helpful for the individual. But I’m also interested in something else, which is your/my heart’s capacity growing, and the courage to feel growing. So can I have that capacity? Can I develop that capacity to feel the pain of the times without denial, or with less and less denial, with less and less numbness, with less and less apathy, overwhelm, or ill-will? None of which is easy. I don’t think that’s easy at all. I really don’t.

It was about a month ago, I can’t remember exactly, and I came across a piece of news on the internet. Maybe some of you saw it as well. It was there for a day or two, then it disappeared. Scientists, marine scientists, are almost certain now [pauses, chokes up] … They hadn’t considered the combination of three factors: (1) climate change, global warming, with ocean warming; (2) ocean acidification; (3) and I think the third one was pollution. Hadn’t considered how those three act together, and concluded in very recent research that there’s almost certainty that we are on the brink, in the next decades, of the largest marine species extinction not in the history of humanity but in the geological history of the earth. So that appeared for a day or two on the internet and then disappeared again.

I don’t know. I mean, that really affects me. I don’t know where it lands with you. I find such grief when I open to that. Or what’s going on in Somalia and the Horn of Africa right now. Again, it appears a little bit and then it seems to disappear. So the famine and the drought there. Perhaps you heard this, too. In that area of the world, of course, sub-Saharan Africa, the rains used to fail every ten to twelve years. That was kind of typical. There would be drought and famine and massive crisis as there is now. Now, more recently, they’re failing every other year, every two years. Why? I didn’t read the next part of the sentence. I would guess from climate change.

And similarly, on the same theme, climate scientists and environmentalists are pretty sure that the chances to limit global warming to two degrees centigrade are pretty much gone. We can pretty much say goodbye to that. We’re looking, at the moment, at more like three and a half or something, which is actually a massive difference, because it’s above the limit that causes runaway climate change. We cannot predict even what happens there.

So how does it feel? How is that? These are our times. This is what we’re living in. Now, I know, and I know for a fact – and it’s really important not to judge here, really important not to judge – sometimes a person cannot find any care in relationship to all that. It just seems abstract, seems like it doesn’t involve me. I’m preoccupied with other stuff. Or something else – for other reasons there’s no care. Could be all kinds of reasons. But if that’s the case – and that’s really okay; it’s really important not to judge here; it’s okay – to gently inquire: what’s behind that lack of care? What’s supporting that lack of care? Why is it that there’s this lack of care? Could be all different reasons. Where does that lack of care come from? That lack of connection, that lack of relationship with not just the earth and the biosphere but also people elsewhere, humans? Someone pointed out, George Marshall pointed out, climate change is principally a human rights issue. Forget about the environment – the earth’s going to be fine. It’s principally a human rights issue, which is a whole other way of looking at it.

Very easily it could be that the lack of care in some cases is from overwhelm, or from a sense of powerlessness: what am I going to do? There are already seven billion people. It’s already all out of control. And that’s just too painful. Or it could be, for many reasons. It’s really important that the inner critic, which Chris spoke about last night, doesn’t come into these kind of inquiries. But there can be a gentle questioning there, a loving questioning. I think what practice can offer is this capacity and courage, to develop the capacity and courage to hold and respond to the world’s pain. Sometimes what we want, because the situation now is so complex and the intricacy on the economic, political, sociological, biospherical, technological, all this come together is so complex, and we want simplicity. I want things to be simple.

I might imagine as a meditator …

that I’m immune to the effects of all this

insidious value manipulation, etc.

And what am I going to do about it?

And that’s interesting, because part of this is asking, “What does it mean to be an ethical human being these days?” The Buddha had a list of five things which Andy told you about, five precepts, on the opening evening – you know, try not to do this and this and this. One of my teachers said that’s great, it’s like you just do that, you take care of it, and then forget about it and don’t wrap yourself up in complexity and guilt. Really wise. But I don’t know how well that fits any more. Sometimes we might want, or a part of us might want to open the textbook, read the list of rules, and tick them off, and it’s all very simple, though it can be helpful. Chris will talk about the eightfold path and the Four Noble Truths. But I wonder if they need expanding nowadays. I don’t know. I think so.

I feel that practice and the path and our whole notion of what we’re doing needs to address our relationship with the world’s difficulties. To me, that seems important. I know some people don’t feel it’s relevant at all, and would even find it weird that I would be giving this talk. You might find it weird that I’m giving this talk right now. I don’t know. You might feel this is a very strange talk to be giving on the second night of a retreat, when people’s bodies are aching, their minds are aching, they’re a bit fed up, they’re wondering if it was really a good idea to come, you’re tired. I know all that. But that was part of the reason for giving it tonight. As I said, I usually give it on the last night. If I think this talk doesn’t fit here, maybe it’s not the talk that needs to move and shift. Maybe it’s my view of what meditation and what practice is that needs to shift, if I feel that addressing these issues doesn’t belong here on the second night, on a night of difficulty.

The world and its events, and the world and its suffering, and the ideas in the world, and the values in the world, and the assumptions in the world, they do affect me. They affect us enormously and insidiously. I can’t turn a blind eye to all that. Yukio Mishima, in a book called Spring Snow, said, “To live in the midst of an era is to be oblivious to its style.”3Yukio Mishima, Spring Snow: The Sea of Fertility, tr. Michael Gallagher (New York: Vintage International, 1990), 95. There’s a lot in the air – in more ways than one – that we’re oblivious of. We just absorb it. We just drink it in, and it becomes how we see.

So what is this situation? I’ve touched on it already, but this is from Lieutenant-General Dallaire. He was the general in charge of the UN peacekeeping mission in Rwanda when there was the genocide there. He said,

At the Canadian Forces Peace Support Training Centre, teachers use a slide to explain to Canadian soldiers the nature of our world. If the entire population of the planet isrepresented by one hundred people [this is from 2006, I think, so it’s out of date, but] fifty-seven live in Asia, twenty-one in Europe, fourteen in North and South America, and eight in Africa. The numbers of Asians and Africans are increasing every year while the number of Europeans and North Americans is decreasing. Fifty percent of the wealth is in the hands of six people, all of whom are American. Seventy people are unable to read or write. Fifty suffer from malnutrition due to insufficient nutrition. Thirty-five do not have access to safe drinking water. Eighty live in sub-standard housing. Only one has a university or college education. Most of the population of the globe live in substantially different circumstances than we in the First World take for granted.4Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire, Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2003), 520–1.

Here’s another thing I came across in a fantastic book called Requiem for a Species by a guy named Clive Hamilton. It’s about climate change. He said,

In 2007, the IPCC [International Panel for Climate Change] updated its assessment of the economic costs of emission abatement [lowering carbon dioxide] by bringing together and assessing the results of a wide range of economic models. What did it show? To be fair, let’s consider the worst case for the economy [in other words, the most expensive it could be], which is usually the best case for the climate. [So doing the utmost you can for the climate at the most cost to the economy.] The most stringent target assessed involves cutting emissions to ensure that greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are stabilised at 450 ppm CO2-e in 2050. The economic model showing the highest cost of reaching this target estimates that pursuing it would cause a reduction of global GDP of 5.5 per cent in 2050. [Okay, all very abstract.] Most models show lower costs.

Bearing in mind that world income will be very unevenly distributed, what would that mean to the typical individual? Global population [according to the UN, average estimate of the UN; they have a range] is expected to increase from 6.7 billion in 2007 to 9.2 billion in 2050. If incomes grow at the anticipated 1.75 per cent each year, average incomes will double by 2047. If we took stringent measures to restrict greenhouse gas emissions so that they stabilise at 450 ppm then, according to the models that show the greatest economic damage, at most the effect on the world economy would be such that the doubling of average incomes would be held up until 2050, a delay of three years. I have selected the most pessimistic numbers. A more typical estimate of the cost to GDP is 2 per cent, which would mean the loss of only one year’s income growth between now and 2050. [He concludes,] A one-year delay in the doubling of average incomes is the basis for the belief that pursuing a safe level of climate protection would be too expensive.5Clive Hamilton, Requiem for a Species: Why We Resist the Truth about Climate Change (London: Earthscan, 2010), 50–1.

You read something like that, you hear something like that, and you think, “What is going on with us as a species? What’s going on?” Something is going on. And I think it’s really complex. I don’t even pretend to understand it. Something is going on. And I certainly don’t want to trash modern culture, which gives us so many gifts. But some of the values and the ideas that underpin modern society and culture basically increase suffering for ourselves and for others, and this is where the Dharma comes in.

Let’s unpick some of this. Back in the seventeenth century, there was this Enlightenment with Descartes and Newton and some other guys. [laughter] And the idea became that we could know an objective reality from a distance – the universe kind of does its thing separate from us, and we can objectively know that. There was at that time (and it has persisted until the modern day, and this is why it’s important) this myth of detached knowledge, of objective knowledge. So Julie Nelson, who’s an economist, said there’s this myth of what she calls “objectivism.” She says it’s a “romantic belief in the possibility of connection-free knowledge from an outside-of-nature, perspective-free viewpoint.”6Julie A. Nelson, “Economists, value judgments, and climate change: A view from feminist economics,” Economics Faculty Publication Series (1 Apr. 2008), ScholarWorks at UMass Boston, 5, accessed 22 Dec. 2019. And it lauds, it praises emotional distance, autonomy, rationality, disinterestedness, and ‘hard’ knowledge – all of which is a deluded self-conception. That persists in the view of nature but also the view of the economy and politics, and – and this will be in another talk – meditation. The whole idea of objectively knowing an experience in meditation is also a myth. But we will get back to that.

So that’s one of the myths and ideas that’s very prevalent. There was also the idea that, similar to this, really people are rational beings. (This is coming out of this last one.) People are rational beings, so really when they get given the facts, and you lay out the facts in front of them, whether it’s about climate change or whatever, they’ll basically see what the pros and the cons and the dangers are, and they’ll choose the rational thing to do. That was assumed for hundreds of years, that that’s what human beings do. But a whole host of recent psychological studies have shown that’s almost never what human beings do. Quite the opposite. In fact, sense of identity and sense of value almost always prevails in what information we accept. So we accept only information that confirms my identity and my values. We mould our thinking around social identity, protecting our social identity. So you present someone with inconvenient facts like something about climate change and the culture, and that tends to actually harden their resistance. They actually close down more. It’s fascinating.

They furthered this research. They were discriminating between what they called ‘extrinsic values’ and ‘intrinsic values.’ I don’t want to go into this in too much detail, but basically extrinsic values are things like caring what other people think about me, financial success, status, that sort of thing. Intrinsic values are caring about my relationships, community, self-acceptance, values that transcend self-interest. People can score differently on these value measurements. Actually we’re all mixed; there’s a mixture there. But it was a pretty good predictor where someone was in terms of their constellation of values, almost 100 per cent a predictor in lots of studies of how they would feel about things like the environment, their relationship with the environment, their relationship with human rights, their relationship with feeling okay about manipulating, and their relationship with things like prejudice.

Okay, fair enough. But again, what does this have to do with the Dharma? All this has to do with Dharma and Dharma practice, so please bear that in mind. There was another sociological survey recently, tracking values and attitudes, a social attitudes survey. It very clearly showed that the culture and the society and the messages in the culture severely shape the values that people feel. So in other words, okay, extrinsic/intrinsic, but they’re shaped by the messages that we’re getting in society, and advertising and media in particular, but also political messages. Advertising and the media, they deliberately generate a feeling of inadequacy: “I’m not good enough. I need to buy this. I need to change that and get this kind of thing,” or whatever. Deliberately generating feelings of insecurity and inadequacy, and the intrinsic feelings are dampened, are squashed, and the rise of extrinsic feelings. Do I think I’m immune to this because I’m a meditator? Maybe I’ve been meditating some decades. Maybe I think, “That doesn’t affect me.”

The more insight I have, the more risks I can take. The more risks I take, the more insight I get. They’re mutually supportive.

A guy called Tom Crompton who works for World Wildlife Fund, a researcher, [says] advertisers employ huge numbers of psychologists. I don’t know if you knew that. They are employed, huge numbers of psychologists, by advertisers. Guy Murphy, who is global planning director for the marketing company JWT – in his words; this is a marketing director speaking:

Marketers … should see themselves as trying to manipulate culture; being social engineers, not brand managers; manipulating cultural forces, not brand impressions.7Guy Murphy, “Influencing the size of your market” (Institute of Practitioners in Advertising, 2005). Cited in Tom Crompton, Common Cause: The Case for Working with our Cultural Values (WWF, 2010), accessed 22 Dec. 2019.

Tom Crompton says the more they foster these extrinsic values, the easier it is then to sell their products. So we have this massive inundation of marketing and messages deliberately engineered to tinker with our values and change our value system. And all that feeds consumerism, feeds the whole mindset of consumerism and individualism. Out of that comes new values, and the whole thing kind of cycles on itself.

This is again from Clive Hamilton. In all that, it makes certain types of thinking and conclusions feel like they’re completely unavoidable, obvious. So something like how we think about economic growth, for instance, and the whole notion of the growth machine. So:

The growth machine, which we thought we had built to enhance our own ends, has taken on a life of its own, and resists fiercely the slow awakening to its perils of the humans it is supposed to serve. The growth machine has, over time, created the types of people who are perfectly suited to its own perpetuation – docile, seduced by its promises and unable to think beyond the boundaries it sets. [Strong language.] The closer some get to the levers of the machine the more they must be committed to its goals. It is hard to imagine that anyone who believes that economic growth is part of the problem would ever be allowed near those levers. More likely they would be ridiculed in the newspapers and denounced in the parliaments. Ordinary people may at times question

the wisdom of relentless growth and conclude that it cannot go on forever, yet they are soon bounced out of their subversive reverie by the inducements to go shopping. The system has created the type of people who are perfectly suited to what it needs, unending expansion.

In this way, the growth system governs itself. We think we have power, but the growth system awards power only to those who will advance its objective. We internalise the discourse … so that we begin to articulate the interests of the system and govern ourselves according to its rules.8Hamilton, Requiem for a Species, 48.

So the whole thing starts feeding on itself. We’re in the middle of that, and Dharma practice is in the middle of that. Consumerism and economic thinking and the values play into each other, and a snowball happens. And, relevant to the practices that we’re doing, the emotions that I feel – how much of them come from the ideas and the values that I have? Ideas and values really give rise to emotions. So a meditator, because a meditator, a practitioner, is interested in delusion, and here is a gross delusion, to me that makes it part of the remit of a meditator, because it’s delusion. With that, there’s a kind of fragmentation of the social fabric – everyone is individually pursuing their ends; we’ve lost the sense of common endeavour, of being in it together, supporting each other in the society. Václav Havel also comments on the sort of current zeitgeist:

We are living in the first truly global civilization. This means that whatever comes into existence can very quickly span the whole world. [We already said that.] We are also living [he continues] in the first atheistic civilization – in other words, a civilization that has lost its connection with the infinite and eternity. For that reason, it prefers short-term profit to long-term gain.9Václav Havel, “Václav Havel, Opening Ceremony | 2010 Forum 2000”, YouTube (recorded 10 Oct. 2010, uploaded 19 Sep. 2011), 8 Jan. 2020.

I think that’s very interesting. I want to return, later on in the retreat, to this whole idea of the infinite and eternity and nihilism, etc. Because I don’t think it’s wrong to be nihilistic, necessarily, but what does it lead to? And if I’m going to be nihilistic, can I be fully, 100 per cent nihilistic, and really go into it and explore that? Because that would be different. But I will come back to that.

So what are our reactions to all this? To me, it’s so complex. It’s so complex, this whole situation. And also complex are the reactions we have. We have to look at ourselves with compassion and have a compassionate look at ourselves. So are my reactions helpful or not? This is always the question in the Dharma – my responses, are they helpful or not? One can hear all this, and about what cities in the world on coastlines will be underwater in X years’ time, etc., and the mind may start going, “Well, the house on the hill is starting to look pretty good. Maybe I can get somewhere that’s a little high up, and the waters don’t reach there.” But it’s also a metaphor, because maybe I won’t be able to afford a house on a hill. It’s a metaphor for kind of taking care of me and mine. But that very self-preservation thinking is part of the problem. It’s part of this. It feeds a kind of disconnection, and in doing that it feeds suffering.

I feel the only way we’re going to relate to this well is if there’s a real sense of “We’re in it together.” When the waters rise, they rise everywhere, for everyone, together, and I’m not going to run up that hill, and shut my doors, and bolt my doors, and stand at the window with a shotgun, or have my wealth preserve a place for me and preserve my security.

I’m running out of time, but it’s very interesting, in this stuff I’ve been reading, the psychology of what happens in relationship to the threat of climate change – which isn’t an immediate danger, and that’s partly why it’s so difficult: I don’t feel an immediate danger with it. But basically there are all kinds of what are called ‘maladaptive strategies’ we can have in response to the threat: denial, distraction, minimizing the threat, distancing it – “It’s just somewhere in the future.” A guy called Anthony Leiserowitz was asked in 2006 to write a report for the US government, and he concluded, on the attitudes of the US population, he said:

As a whole, the American public is currently in a ‘wishful thinking’ stage of opinion formation, in which they hope the problem can be solved by someone else without changes in their own priorities, decision making, or behavior.10Anthony Leiserowitz, “Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values,” Climatic Change, 77 (2006), 63, accessed 8 Jan. 2020.

So there’s a kind of just, “Mañana, mañana.”

Pleasure-seeking is another maladaptive strategy. Blame-shifting – it’s easy to blame China now because of all their coal-powered plants that they’re building. Apathy. What Clive Hamilton calls a false optimism – he says about that: “[Scientific] observations of climate change have taken such an alarming turn in the last few years, and global action remains so inadequate,” that pretending to oneself that it’ll work out is a dangerous “disconnection from reality.”11 Hamilton, Requiem for a Species, 132–3. It’s actually a kind of disconnection from the reality of things.

So it might not feel painful. Sometimes people don’t feel any pain with relation to this. But I wonder about an analogy with that. You know, you can have cancer and be in a life-threatening situation, or HIV, and there’s no pain – up to a certain point. Or maybe a more accurate analogy: I worked for a very short time in a leprosy community in India. I didn’t know this until I got there, but the problem with leprosy, why they lose their fingers and things, is because what they actually lose with the disease is the nerve functioning in the extremities first. So they put their hand in a fire or something, and they don’t actually realize that it’s hot, because they don’t feel it. The fingers get burnt and infected, and they lose them.

Can I learn to tolerate these feelings, really tolerate? This what I said earlier, this capacity, and we said on the opening talk the range of the human heart and the capacity of the human heart is extraordinary. Can I learn to tolerate the feelings, say with climate change? I’m using climate change just because it’s, in a way, perhaps the most pressing issue of our times, and certainly the most comprehensive. Tolerate the feelings of, say, realizing that a major disruption – above those two degrees, which would trigger runaway climate change. Can I tolerate those feelings that a major disruption in the climate is probably no longer avoidable? What does that do? Can I tolerate those feelings? Can I practise so that I can tolerate those feelings? So all kinds of unhelpful relationships and reactions we can have to all that. But also helpful, also helpful. And I don’t have any easy answers at all, and I don’t actually think anyone does.

This hour in history needs a dedicated circle of transformed nonconformists … the creative maladjustment of a nonconforming minority…

So ‘turning out.’ I call this talk “The Meditator as Revolutionary.” So turn in and turn out – revolution means ‘to turn around,’ ‘to turn out.’ In a way, when I turn out the attention in terms of suffering, it’s also relieving. I feel this pain in life, and as I said earlier, maybe my pain in my life is not my fault. Maybe it’s not my fault. Why can’t I get it together? Maybe it’s not my fault. Maybe it’s the fault of the fabric of the society that we live in. This is from James Hillman, a psychoanalytic thinker:

It’s only depressing if you are in the posture of the child and feeling powerless and then there’s still another big thing out there to blame and you can’t do anything about it. But for me it doesn’t feel depressing, it feels relieving, immensely relieving to know that it’s not me that’s at fault and I don’t have to own and be the cause of all my misery. There’s something fundamentally wrong in the society and this relieves me of the blame, first of all; and second of all, it relieves me of the guilt; and third, it excites me, draws my attention outside to more than myself. That’s not depressing.

So he’s a psychotherapist, and he thinks a lot about therapy, and he’s in the therapy world, and he’s saying:

Therapy could be causing depression as much as curing it [so everything he says about therapy, we could say about the Dharma and practice], because the classic symptoms of depression are remorse, a concentration on oneself, repetition – “What’s wrong with me? How did it get this way? I shouldn’t have done that.” Feeling poor and broke and without energy – in other words, a withdrawal of libido from the world. The moment you’re focusing back on the world as dysfunctional, you’re drawing attention to the world. That’s not depressing.12For the next few Hillman/Ventura quotes in this talk, see James Hillman and Michael Ventura, We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy – And the World’s Getting Worse (New York: HarperCollins,

1993), 230–1, 219, 151.

He also, in conversation with a guy called Michael Ventura – fascinating conversation to read – they’re talking about different kind of therapy situations. This is a conversation between them.

Ventura: It’s not just your parents, your childhood –

Hillman: – or my relationship with my marriage. There is a dysfunction in the society that is affecting us. And the second step is: I cannot repair it in myself in my own relationships alone, because my problem is social dysfunctions. So how is settling things with my wife going to repair the dysfunction of the general situation? That’s a romantic delusion – that if we could just get our sex right, our conversations right, “if I could just find the right relationship –”

Ventura: “If my little home could be perfect, could be safe – if I could find balance in my home I’d be happy. Talk to my kid, talk to my wife, quit drinking, get laid decently a couple of times a week, get on a decent diet, get exercise, make a little more money, then I would really be okay.” Except you won’t. Because you still live in this crazy world of dysfunction that impinges on you and influences you and yours twenty-four hours a day.

Hillman: “Where the school isn’t right for my kids, where the food I eat is not right, where the air I breathe is not right, where the architecture in which I spend my time assaults me, the lighting and the chairs and the smells and the plastic are not right. Where the words that I hear on TV and are printed in the newspaper are lies, where the people who are in charge of things are not right because they are hypocritical and hiding what they are really doing – so how can I ever get it right within my home and within my marriage?”

Ventura: One of the things we are saying is: You can’t make a separate peace. You can’t sign a peace treaty with society through therapy.

And I would add, “Or meditation or Dharma practice.” They talk about, say, for example, working with an eating disorder. People go to a group and discuss and support each other with an eating disorder. But actually you have to include in that conversation, “In my group from now on, we must talk about agribusiness, fertilizers, pesticides, packaging, advertising, school lunches, fast foods, diets. We have to talk about the entire thing because that’s the situation and that’s what’s impinging.”

So, meditator as revolutionary. Turning in, turning out. Caroline Lucas, MP now, I heard her speak, and she was calling for national acts of civil disobedience. From an MP. Cool. [laughter] I don’t know. You decide what it means, meditator as revolutionary. You decide what that means for you. I need to look at my stuff, definitely. I need to look at my stuff. That’s what we’re doing. We’re really looking at my pain and my stuff. One of the words that ‘dharma’ means, the original word ‘dharma,’ also one of its meanings is ‘duty.’ It’s interesting. One of its meanings is ‘duty.’ So we think, what is my duty in life? What is my duty to my family, my parents as they grow old, my children, my spouse, my partner, whatever it is? What’s my duty? ‘Duty’ can be a heavy word for us, though. But what is my larger duty or my larger love, and the movement of my larger love? All this, to me, very much affects Dharma practice and how I feel I need to think about and relate to Dharma teaching.

This is James Hillman again. If you’ve never heard of him, he was head of the Jung Institute in Zurich. He was at the head of the Jungian psychotherapy world for ten years or something. He was head of the education department. He’s totally embedded in the psychotherapeutic culture for decades. He’s probably in his late eighties now. He comments a lot on that culture, but from within. So he’s not an outsider. He says,

Suppose we entertain the idea [he’s a very radical thinker] that [psychotherapy] makes people mediocre; and suppose we entertain the idea that the world is in extremis, suffering an acute, perhaps fatal, disorder at the edge of extinction. Then I would claim that what the world needs most is radical and original extremes of feeling and thinking in order for its crisis to be met with equal intensity. The supportive and tolerant understanding of psychotherapy is hardly up to this task. Instead it produces counterphobic attitudes to chaos, marginality, [and] extremes. [Strong words now.] Therapy as sedation: benumbing, an-aesthesia so that we calm down, relieve stress, relax, find acceptance, balance, support, empathy. The middle ground. Mediocrity.

Strong words. Everything that’s said there, I have to ask myself, as a Dharma teacher, am I supporting that? Is that what I’m in the business of doing? I have to be careful what I say. I feel I really need to be asking myself these questions. What am I modelling as a Dharma teacher? Am I modelling a kind of nice security of fitting nicely in as a well-respected citizen … Am I modelling that? Well-adapted, well-trained, well-tamed? So again, I might imagine as a meditator – I’ve been meditating; I’m conscious because that’s what meditators do; we’re into consciousness – I imagine then that I’m immune to the effects of all this insidious value manipulation, etc. So do I imagine that? And what am I going to do about it? This is from Bhikkhu Bodhi, who is a monk and a translator of the original Buddhist texts:

The special challenge facing Buddhism in our age is to stand up as an advocate of justice in the world, a voice of conscience for those victims of social, economic, and political injustice who cannot stand up for themselves. This is a deeply [ethical] challenge marking a watershed in the modern expression of Buddhism.13Bhikkhu Bodhi, “A Challenge to Buddhists,” Lion’s Roar (1 Sept. 2007), accessed 22 Dec. 2019.

The Buddha said, “The gift of the Dharma is the highest gift [you can give someone].”14 Dhp 354. But what is the Dharma? What is it? To me, the Dharma is about values. So when I’m teaching the Dharma, I’m also teaching about values, values that matter, values that go deep. What that means is if you, if I, want to give the gift of the Dharma, it means speaking up about values. It means engaging this debate, starting a debate in the culture about values, a deep revolution in the discourse about values in our culture.

But this is hard, you know. I don’t have any simple answers at all, and I’m fascinated and flabbergasted at the complexity of it all and the difficulty of it all. It seems like we need a long view, somehow. Our time is running out, and we need a long view. Michael Ventura has a very lovely passage. He reports this in conversation. He says,

Just around when he was turning thirteen my kid came home one night, after dark, sat on the couch, and in a kind of fury …

This is a thirteen-year-old boy and, you know, the sensibility is there; the tenderness is still there, and the eyes are opening at that age, and the adventuring is happening. So this tenderness and this openness of sensibility is going out to the world and exploring the world.

He came home one night, after dark, sat on the couch, and in a kind of fury suddenly burst out with, “It’s fucked, it so fucked, man, the whole thing is fucking fucked. What do you do in this world, man?” What could I say to him, that things are gonna be all right, when they’re not? That it’ll be okay when he grows up and gets a job, when it won’t? I got a little crazy and impassioned and I said something like this:

That we are living in a Dark Age. And we are not going to see the end of it, nor are our children, nor probably our children’s children. And our job, every single one of us, is to cherish whatever in the human heritage we love and to feed it and keep it going and pass it on, because this Dark Age isn’t going to go on forever, and when it stops those people are gonna need the pieces that we pass on. They’re not going to be able to build a new world without us passing on whatever we can – ideas, art, knowledge, skills, or just plain old fragile love, how we treat people, how we help people: that’s something to be passed on.15Hillman and Ventura, We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy, 236.

Maybe you know the story: “Once upon a time, two masons worked on a building site. A passing pilgrim asked the first what he was doing. ‘I’m just chipping away at another block of rock until payday on Friday,’ the man replied. The pilgrim turned to the second who said, ‘I’m building a great cathedral that will not be finished until long after I’m gone.’” We need that long view. And what’s the difference? It’s so easy for fear to come up in relationship to all this, or for people, and I’ve heard people say – Dharma practitioners, even, seasoned Dharma practitioners – say, “I don’t get involved in all that because it’s just going down the road of fear.” But what’s the difference between fear and concern? What’s the difference between being afraid and being concerned? There’s a big difference.

To me, concern has stability, rootedness, strength, and balance in it, which fear does not. The same person also said, “I don’t go there because it just seems like a lot of anger, getting angry.” But again, I would ask: what’s the difference between anger and ill-will? Ill-will is when I want to hurt someone, when I want to put someone down and make them suffer. We could say anger is ‘energized responsiveness’ at something that’s not right, but I don’t want to hurt anyone.

Out of all that can come a fearlessness. That’s possible for us, that there can be a fearlessness in relationship to all this – just as much as in relationship to our emotions, also in relationship to the world situation. There was a practitioner called Jesse Maceo. There was an interview with him ages ago. He’s interesting because he takes quite a strong stance. He refused to pay taxes in the US because of military funding through taxes, etc. He was asked to explain himself and he basically said:

The deeper I go into my practice … the less [I’m willing] to behave in ways that diminish my sense of purpose on this Earth.16 Barbara Gates and Wendy Johnson, “Interview with Jesse Maceo Vega-Frey: Scaling up Liberation,” Inquiring Mind, 26/1 (Fall 2009), accessed 22 Dec. 2019.

Takes a really strong stand. So I don’t know what that means for you, what it means. I know that part of practice is taking risks. I know that for sure, that to deepen in practice involves taking risks. And taking risks and insight feed each other. The more insight I have, the more risks I can take. The more risks I take, the more insight I get. They’re mutually supportive. I don’t know what that looks like.

It’s interesting. I don’t know if perhaps you feel a lot about this stuff that I’m talking about. Perhaps you feel a little bit. But you might also notice that in certain groups or situations or with friends, there can be a fear or a hesitancy or a reluctance to speak up, that it becomes uncomfortable in the room. Or they might think I’m such-and-such or whatever. A fear of speaking out – is that something that I need to be constrained by, or can I be radical? Can I let my voice sing out, my concerns sing out?

Hannah Arendt, writing after the Holocaust, a commentator on the Holocaust and other things:

There was once a wicked time when intellectuals grew feebleminded and declared life to be the highest good. But … death begins his reign of terror precisely when life becomes the highest good. [She goes on to say:] If you are no longer willing to die for anything, you will die for having done nothing.17 Hannah Arendt, The Jewish Writings (New York: Schocken Books, 2007), 163.

Now, she was talking about the Holocaust, but why I bring that up is: what’s going to give me a freeing perspective on this, a powerful perspective in relationship with all this? Psychological studies, also, recently – there have been a host that show if you think about death a little bit, just a little bit, you tend to get more selfish and more self-interested. So being reminded of death tends to stimulate the self-interest and selfishness and self-protection. Thinking about death a lot, about your mortality, has the opposite effect. It releases, we let go of self-interest and self-imprisonment. So the contemplation of our mortality actually is quite central here. It relativizes the whole relationship with self and other and existence. That’s a factor. Less self-focused values. Obviously the practices we’re doing, and developing this capacity to hold what’s moving through – so I can hold my own individual pain; eventually maybe I can hold this bigger pain, too. And I can, and it’s possible. It doesn’t mean it’s not going to feel like a lot, but it’s possible, absolutely possible.

And we haven’t talked about this yet on the retreat: there are these very deep teachings of emptiness in the tradition, and a whole re-understanding of the nature of existence and reality. That brings with it equanimity, deep equanimity, deep spaciousness, deep strength, and deep courage in relationship to all this.

So I want to finish just with some words from Martin Luther King. I was in London some months ago and I met – I don’t know what she did exactly; I think she was a bit of an artist and a bit of a journalist working in environmental areas. She had been to some conference with lots of dignitaries and kings and queens and world leaders and stuff. It was on nuclear disarmament, but every time they talked about nuclear disarmament, they kept prefacing it with, “It’s the second most urgent problem of humanity.” They kept saying it’s the second most urgent problem, the first one being climate change. So when Martin Luther King said this, I think he was talking obviously about civil rights, but also about the threat of nuclear catastrophe in the sixties. But to me it applies as strongly today:

This hour in history needs a dedicated circle of transformed nonconformists…. The saving of our world from pending doom will come, not through the complacent adjustment of the conforming majority, but through the creative maladjustment of a nonconforming minority….

Human salvation lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted.18 Martin Luther King, Jr., A Gift of Love: Sermons from Strength to Love and Other Preachings (Boston: Beacon Press, 2012), 18–9.

Shall we have some silent time together?

This talk was given during the Boundless Heart Retreat in 2011.

References

- 1J. D. Salinger, Franny and Zooey [Kindle edn] (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1955).

- 2e.g. in SN 22:86 and SN 44:2.

- 3Yukio Mishima, Spring Snow: The Sea of Fertility, tr. Michael Gallagher (New York: Vintage International, 1990), 95.

- 4Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire, Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2003), 520–1.

- 5Clive Hamilton, Requiem for a Species: Why We Resist the Truth about Climate Change (London: Earthscan, 2010), 50–1.

- 6Julie A. Nelson, “Economists, value judgments, and climate change: A view from feminist economics,” Economics Faculty Publication Series (1 Apr. 2008), ScholarWorks at UMass Boston, 5, accessed 22 Dec. 2019.

- 7Guy Murphy, “Influencing the size of your market” (Institute of Practitioners in Advertising, 2005). Cited in Tom Crompton, Common Cause: The Case for Working with our Cultural Values (WWF, 2010), accessed 22 Dec. 2019.

- 8Hamilton, Requiem for a Species, 48.

- 9Václav Havel, “Václav Havel, Opening Ceremony | 2010 Forum 2000”, YouTube (recorded 10 Oct. 2010, uploaded 19 Sep. 2011), 8 Jan. 2020.

- 10Anthony Leiserowitz, “Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values,” Climatic Change, 77 (2006), 63, accessed 8 Jan. 2020.

- 11Hamilton, Requiem for a Species, 132–3.

- 12For the next few Hillman/Ventura quotes in this talk, see James Hillman and Michael Ventura, We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy – And the World’s Getting Worse (New York: HarperCollins,

1993), 230–1, 219, 151. - 13Bhikkhu Bodhi, “A Challenge to Buddhists,” Lion’s Roar (1 Sept. 2007), accessed 22 Dec. 2019.

- 14Dhp 354.

- 15Hillman and Ventura, We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy, 236.

- 16Barbara Gates and Wendy Johnson, “Interview with Jesse Maceo Vega-Frey: Scaling up Liberation,” Inquiring Mind, 26/1 (Fall 2009), accessed 22 Dec. 2019.

- 17Hannah Arendt, The Jewish Writings (New York: Schocken Books, 2007), 163.

- 18Martin Luther King, Jr., A Gift of Love: Sermons from Strength to Love and Other Preachings (Boston: Beacon Press, 2012), 18–9.