To become the beloved;

as the world ends, to enter

the last note of its music.

April, 1994. I leave Berkeley with my daughters, Nora (who is fifteen and a half) and Viva (who will be ten in June), for Las Vegas, Nevada, where we will join a group of people from the Buddhist Peace Fellowship for a vigil in celebration of Buddha’s birthday at the nuclear test site in Mercury, an hour’s drive north.

We are to prepare as a community to make this witness. For three days our group of sixty people will eat, study and reflect together, and on the fourth day we will drive to the test site and perform a ritual for the baby Buddha and make whatever protest each of us chooses to make. As part of our study, we are planning to take a D.O.E.-guided tour of the test site. Before our departure I have checked with the Nevada Desert Experience (a group which sponsors nonviolent protest and interfaith vigils at the site) about the advisability of bringing Nora and Viva inside the site, and I have been told that unless a bomb has been detonated within seventy-two hours the site is considered safe to visit.

So I drive with the girls through the springtime Mojave. The magenta flower of the beavertail cactus is in bloom, and the Joshua trees stand crooked and whimsical against the clear blue sky, their pink and yellow petals emerging from spiky forbidding trunks. So much land under so much sky, so many small lives enduring such harsh contradictions. I am thinking, as I drive, of the devastated land at Yucca Flat—part of the test site which once must have looked like this land, which once must also have been fragrant with creosote, with pungent sage, with the resinous gray-green leaves of brittlebush. Each desert plant—low to the ground, spaced widely apart from its neighbors—stands out in the morning air with its singular nature, shaped by the harshness, shaping the horizon along with the distant black volcanic rocks. A few purple and yellow wildflowers—milkweed, verbena, desert chicory—are starting to bloom, their lives exquisitely delicate in their first beginning. A lizard darts across the road. How many others are hidden, how many snakes and spiders and tortoises move now in the shadows of these plants, quickly or slowly, as is their way?

As we approach Sedan Crater, it is clear

that something here is, indeed,

very wrong.

The flora and fauna of the test site—somewhat different from that of the Mojave, influenced by particular conditions of soil and weather—have been extensively studied to establish the effects of radiation on natural communities. Yet, in 1951, when the U.S. government wanted a testing location to replace the fallout-devastated Marshall Islands, they labeled the Nevada Desert “virtually uninhabited”—in a single phrase erasing each desert insect, reptile, mammal, the colorful, infinitely varied plant life, the intricate life of the soil, and the Shoshone, to whom this land has been granted by treaty.

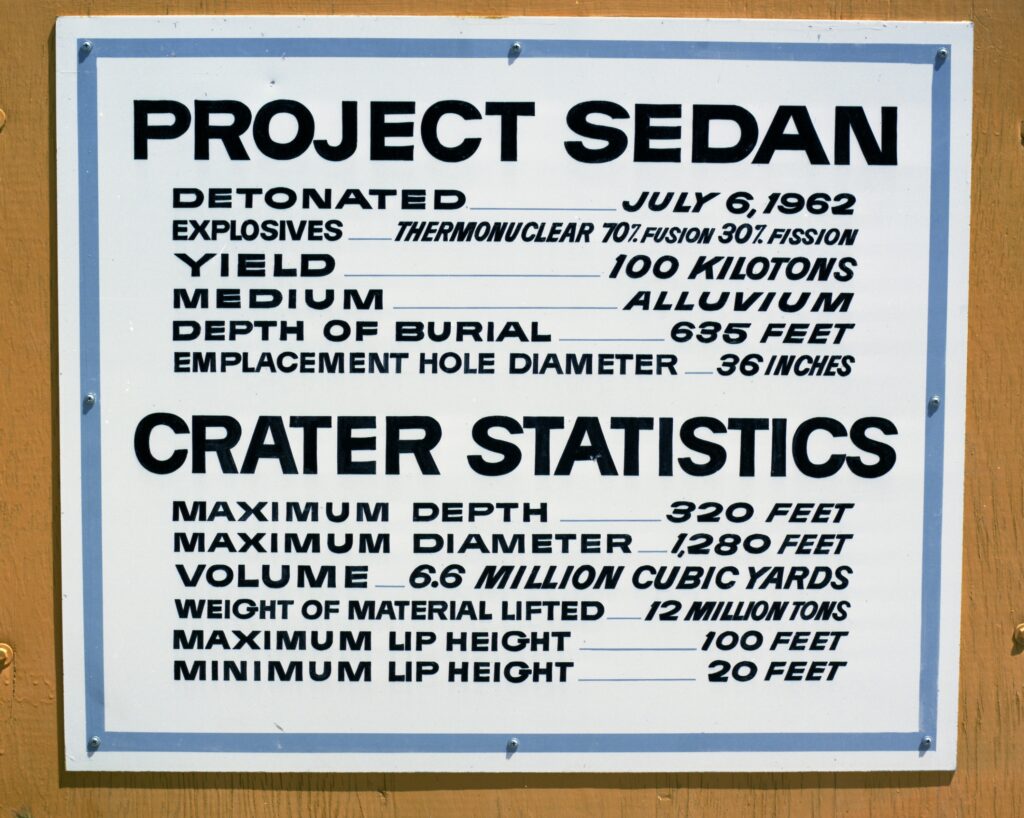

On the eve of our visit to the site, one of the leaders of our group tells us that a place included in the tour, Sedan Crater—where, in 1961, a bomb two hundred times the strength of the one exploded at Hiroshima was detonated—may have a concentration of radioactivity still high enough to pose some danger. No one can give us precise information; the people from Nevada Desert Experience tell us simply that we should give some thought to whether or not we want to get off the bus when it makes its regularly planned stop there.

As we ride in the bus the following morning, the vast expanse of desert stretching before us and behind us, I imagine for a moment what it must be like to be a tiny creature living in this place—an ant, a lizard. I am overwhelmed by my smallness, by the immensity of what I do not understand. But, as we approach Sedan Crater, it is clear that something here is, indeed, very wrong. It is a big bare hole where nothing—nothing!—has taken root for thirty-three years. Not a bush, not a weed, not a blade of desert grass.

I explain to the girls again what we have been told about Sedan Crater. But I do not forbid them to get off the bus when it makes its stop there. Now, as we pull to a halt, the bus is buffeted by a strong wind. Dust is driven against the windows and blows into the bus when the door swings open, brown desert dust stirred up as we have seen it in the Mojave, in the deserts of New Mexico. “We’ve all got it now,” someone cracks from a back-row seat. “Whether or not we wanted it.”

We look outside. Sedan Crater is a great round wound in the earth—barren, devastated, unregenerate, destroyed. Everyone on the bus grows silent, the kind of silence one might feel before anything that inspires awe: a grove of ancient sequoia, a cathedral. A few people settle into their seats, take out material to read or write or draw with. I zip up my sweatshirt and stand, and when Nora says to me solemnly, “I want to see it,” I do nothing to stop her. Isn’t the dust blowing anyway through the open door? I nod silently and zip her windbreaker up to her chin, as I did when she was small. I caress her hair, take her hand, ask one of the people who has decided to stay on the bus to look after Viva—as though we were going, Nora and I, much farther than a mere fifty yards from this bus. And Nora and I step down and walk toward this wasted place, this place where a bomb two hundred times the strength of the one exploded at Hiroshima was set off in the silence of the desert. And we are a silent procession, more like monks now than protesters, I think, everyone pulling up hoods, buttoning jackets. The wind is fierce and chilly. We walk in silence, and in silence I feel someone reach for my hand. It is Viva. I look at my child and start to cry; she has one hand in my hand and the other in her sister’s. I take the scarf from around my neck and tie it over her nose and her mouth.

We are standing together before Sedan Crater, before this open wound: my two daughters and I and the others who have come here with us, whom—until yesterday—we had never met, whose lives now are intertwined with our lives, and with the lives of others who have been here before us and will come here after us, and with the lives of all those, human and animal and insect and bird and plant, who have been affected by the explosion of this bomb and other bombs, forward into time—everyone yet to be born, and all those who cannot believe that they suffer from what they cannot see, all those who do not know and will never know, who (like the lizards and the desert grass) can give no consent.

And the word “communion” comes to me, standing here with my daughters, in this silence filled with the sound of the wind: we are taking communion with all that has been touched by what was done here—downwinder, worker, visitor, desert rat, tortoise, spider, rock, plant, soil. We are knowing in this way our radical interbelonging: this dust, this air, these elements from which one day our bodies will be indistinguishable. We standing here—and all other living beings on this planet—have been altered by what we are now seeing at Sedan Crater. How could standing and looking at this horror fail to make us know that we are wounded with the wounded body of our earth?

I think it is because we love this world that we demand of ourselves to face the evil that ravages it.

And it is our darkness, our destructiveness, with which we are taking communion. Yet, as my gaze moves between the terrible pit and the faces of those who stand staring into it—earnest, unflinching—I find myself overwhelmed with tenderness. How beautiful we are—hair blowing, eyes steady—how beautiful the land we have traveled through to arrive here. I think it is because we love this world that we demand of ourselves to face the evil that ravages it. Facing that evil, we awaken over and over to the stark fragility of what we love, and we are moved to a deeper cherishing of it.

But afterward I am haunted by what I have done in allowing my children to stand with me and stare into the void at Sedan Crater. Have I, too, contributed to harming them? Have I colluded in their contaminating themselves, and their unborn children and grandchildren, forever? Is there, from this moment on, in these two bodies—which I have held and nursed, bathed, fed and kept warm, soothed to sleep in fear and fever—some dark cell changing its course, some seed changing shape, some rhythm interrupted, touched by this dust of bleak communion, some galloping wrong beginning?

I will never know. What I do know is that each of us—my children and I, the strangers and companions who stood with us that day—has tasted the seeds of death in making this journey into the shadows of our humanness and in witnessing there our capacity to put an end altogether to living and growing. There is no way of determining for certain what these moments of witnessing might have done to our bodies, any more than we can be certain of how we will be affected by anything we choose to do. Once we know that everything on this earth is, has been, permeated by what happened at Sedan Crater—and by all within us that makes Sedan Crater possible—then where can we go to shelter ourselves? And how can there be a single place on this earth we do not call home? Once the illusion that we can keep ourselves safe is shattered, what protection is there other than remaining awake?

And certainly something has been awakened in us, as the rain that started falling later that afternoon touched the desert soil and awakened here a sprig of wild yellow buckwheat, there a stem of lavender tamarisk. We touch and awaken, the world touches us and we awaken: delicate plant, wildly dividing cell, imagination, love.

And certainly what we saw there, what we came to know, to understand in that place—the communion we took there, the body of the world we entered and were entered by—has changed us profoundly. Each of my daughters has since referred to the experience of Sedan Crater—and the visit to the site as a whole—as one of the most important in her life, and it was Viva who insisted (in the face of my hesitation) in 1995 that we return to the site to participate in the Hiroshima memorial. At eleven, she told me, “We’ve already made a commitment to this issue; how can we turn our backs on it now?”

Over and over again—alongside my concern for whatever harm might have come to my children’s bodies—I return to my faith that their spirits have been enlarged by their having looked upon Sedan Crater. Over and over again I return to my belief that the spirit, at least, can withstand and ripen the suffering it beholds. I am strengthened in this by remembering that the Buddha, sheltered by his father from sickness, old age and death, chose to know them. Knowing them, he did not flee. He did not retreat behind the palace walls, but rather committed himself to awakening more and more fully.

Once the illusion that we can keep

ourselves safe is shattered,

what protection is there other than

remaining awake?

The final morning of our stay in Nevada, we gathered outside the gate to the test site to celebrate Buddha’s birthday. Nora and Viva and another child who was with our group rang a bell made from an American bombshell dropped in Vietnam. Many of us had first done walking meditation in the surrounding land, gathering small new wildflowers to place as gifts on the altar: red, yellow, purple. The air was bright and crisp; a wind blew the delicate stems of the still-rooted flowers so they bent back toward the earth from which they had arisen and stood again, hardier than they appeared. As we stood, then, in a circle, bell ringing, each person walked in turn to the altar made of desert rocks; each one took a ladle of water and bathed the head of the statue of the baby Buddha, in silence or speaking some words to the desert sky. I looked at Nora and Viva, their hands red from the cold, earnestly taking their turns ringing the bell and then taking their turns bathing the Buddha as though he were a real child: carefully, tenderly.

A few hundred yards from us was the boundary that had been made between the land where the bombs are tested and the land where they are not tested. A false division, I thought, standing there, for clearly the earth this side of the gate reverberates as deeply with the explosions as that on the other side.

What limits can we draw? What protection is there? And what detachment is possible on this earth, where everything is interpenetrated by everything else? How could we transcend that which we touch, which touches us—that of which we are made, by which we are changed? How can we separate ourselves—body, mind, spirit—from all that with which we continually take communion?

This article originally appeared in the Fall 1997 issue of Inquiring Mind. It is shared here under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.