All images © Diane Barker and reproduced here with permission.

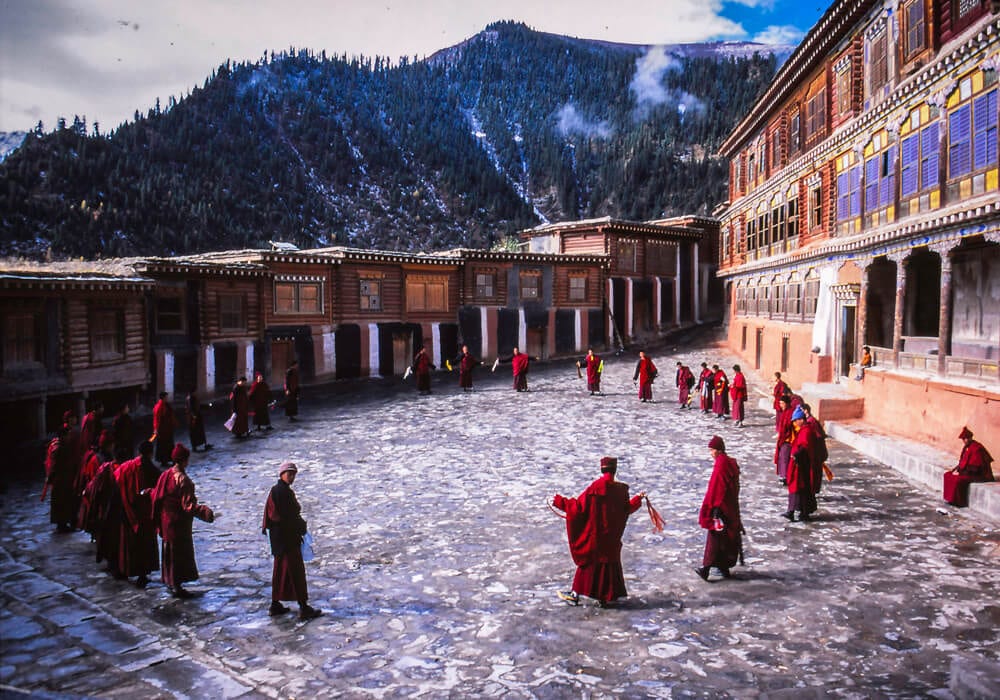

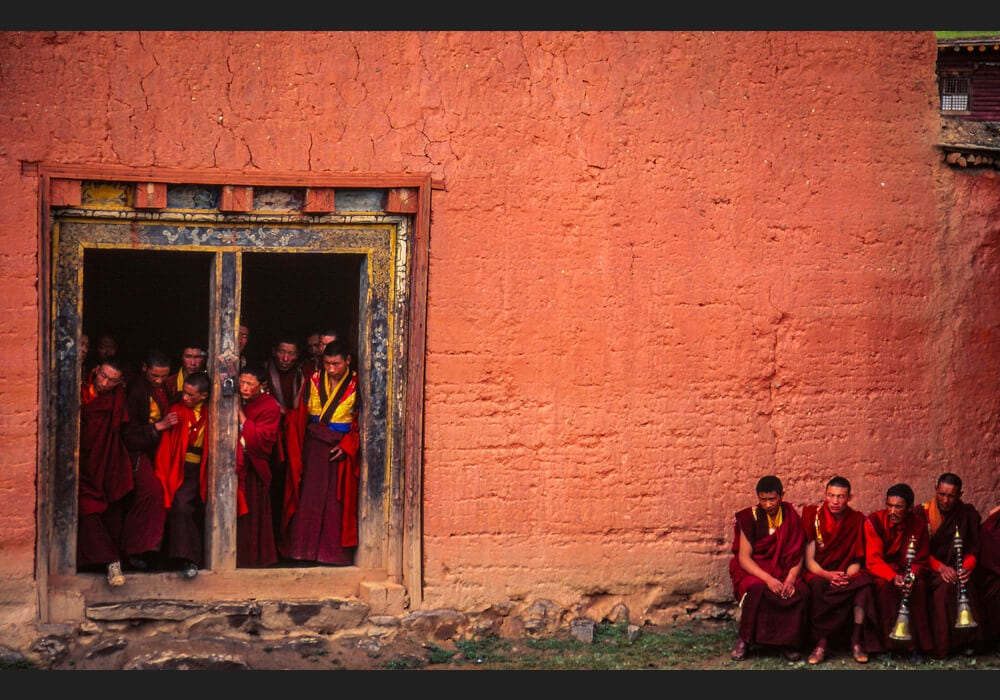

Few outsiders to the Tibet-Qinghai Plateau have had the same access as Diane Barker, a painter-turned-photographer who has moved in diverse circles across Asia since the 1990s. Since 1978 she has maintained a strong connection with Vajrayana Buddhism, and by 1994 she acted on her fascination with Tibetan culture and began taking photos of different Tibetan communities in India. At present, her photographic focus is on the drokpa, which translates roughly to “people of the solitudes.” These nomadic communities embody the oldest traditions of life in this remote region: patterns of herding, horsemanship, and kinship bonds that date well into the earliest periods of Tibetan history.

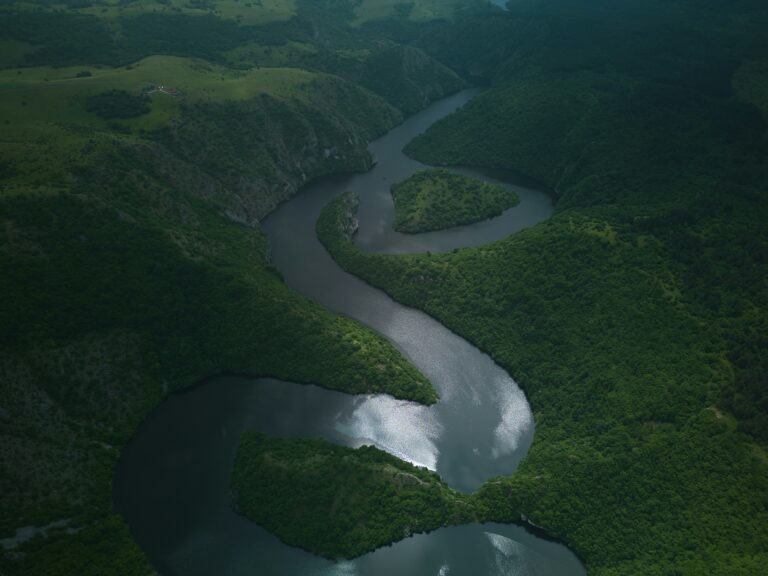

Diane has come to appreciate how the nomads’ stewardship of the land, which she describes as gentle, self-sustaining, and organic, is very pertinent today and can teach us important things amid the global climate crisis. “They live their life in harmony with the seasons and are mindful of the health of their animals and that of the high-altitude grasslands. Nomads have always been very careful not to harm their environment. Anything they no longer needed was easily biodegradable—clay stoves, for example, were left behind to disintegrate back into the earth when they moved on. Their footprint was very light,” she notes.

“Tibetan nomads are not driven by market forces and consumerism, and live their traditional lifestyle in preference to a settled urban one. Traditionally yaks (and often sheep and goats) provided the drokpa with most of their needs: food, wool for clothes and their tents, hides for bags, dried yak dung as fuel for their stoves, and so on. For other needs, such as barley for tsampa, Tibetan nomads operate as a small co-operative, to barter with farmers in the valleys.”

If and how the nomads can sustain their lifestyle is another question. Recent years have seen motorbike culture replacing the use of horses. Many nomads have moved to the edges of ever-expanding Tibetan towns as a result of government resettlement policies or to be nearer to schools and hospitals, and struggle with finding new livelihoods and adaptation to peri-urban life.

The very definition of Tibetan nomadic life is that they are surrounded by the grandeur and vastness of nature. Barker’s photos reflect the drokpa’s intimate connection with their physical environment. How will they cope with being separated from it? How are we in the West coping with our own separation from nature?

“The Tibetan belief that the land is sacred, animated by earth-protector spirits (that they should respect and not offend), demonstrates their sensitivity to and protection of their environment. Unfortunately, we in the industrialized world have long lost the belief that our earth is sacred. We exploit and plunder it as if it’s an infinite resource, but if we learned from the nomads, and Tibetans in general, we would think carefully about everything we do in relation to our mother the Earth. We have forgotten that we are one with her. Sadly, separation seems to dominate our global consciousness in these times and, if we do not heed the warnings of our Earth—floods, wildfires, melting glaciers, loss of species—it could lead to our extinction.”

(This article is adapted from one that appeared in Buddhistdoor in November 2019 titled Visions of Spiritual Ecology: Diane Barker’s Photography of Tibetan Nomadic Life in China. Barker’s photos can also be found on her website, https://www.dianebarker.net/.)