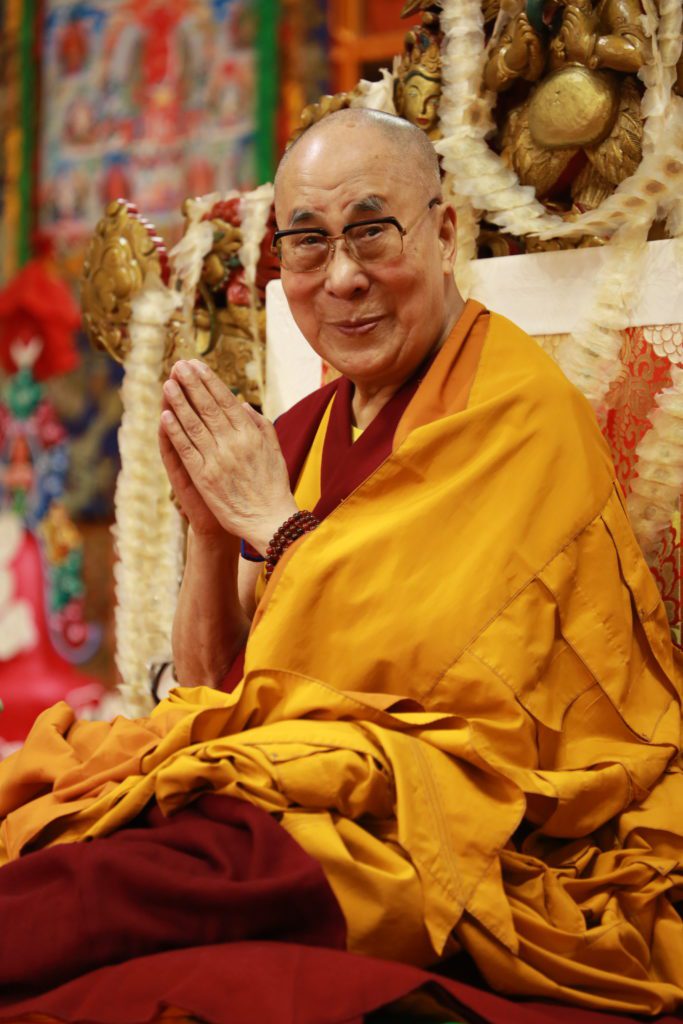

The responsibility of the Dalai Lama (in Tibetan, tā la’i bla ma, or ཏཱ་ལའི་བླ་མ) to Tibet and to the whole of the living world is, and has been for, according to tradition, all of time, almost impossibly massive in scale. As popular saying goes, Chenrézig (spyan ras gzigs, or སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་), the bodhisattva of whom the Dalai Lama is said to be a reincarnation, serves as the “perceiver of the world’s crises.” The Indian Karandavyuha Sutra describes him as “thousand-fold” in arms and eyes, the multiplicity of which later texts in China’s Tang Dynasty (618-907) attributed to the enormity of his vow to end the suffering of all beings.1Wang, Michelle, 2013. Thousand-armed and Thousand-eyed Avalokiteshvara

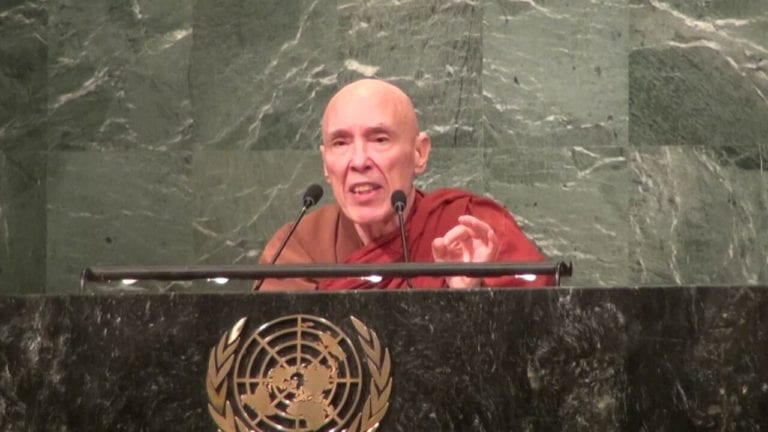

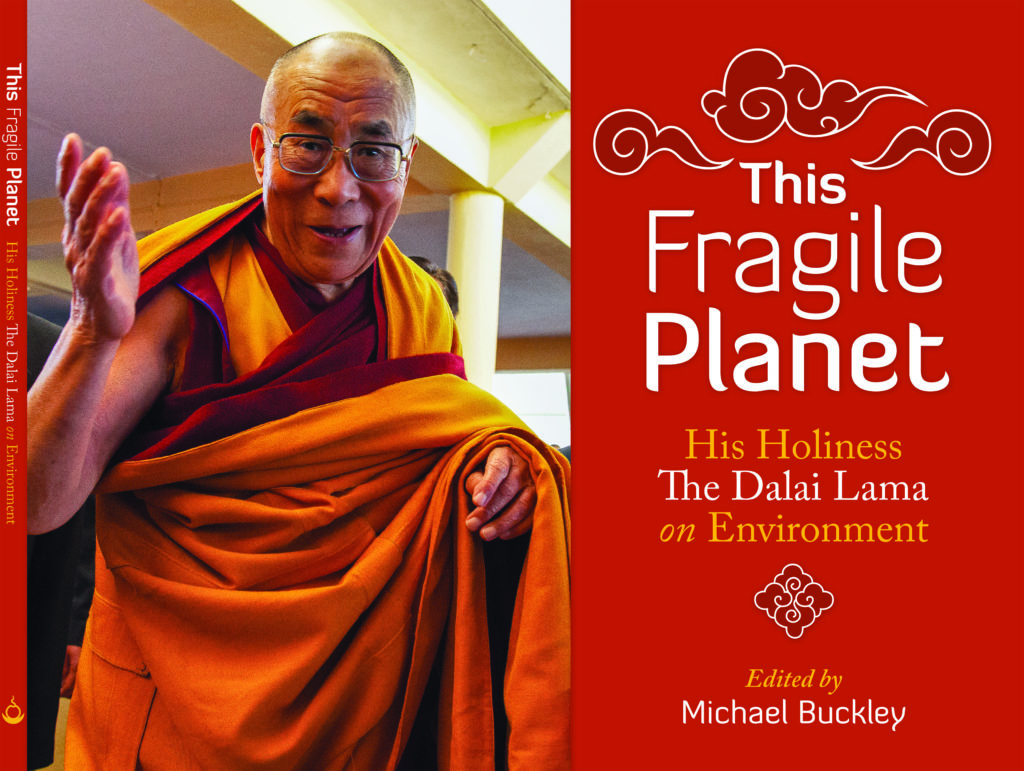

Such a many-pronged defense against suffering certainly appears necessary in the face of contemporary environmental devastation. As This Fragile Planet works to underline, the guidance afforded by the current Dalai Lama has been just this. The publication, set for release from Sumeru Press later this month, is a mosaic effort composed of relatively brief quotations (drawn primarily from His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama on Environment: Collected Statements 1987-2018) and sweeping photographs of Tibetan landscapes and the Dalai Lama himself.2 Credit here is due largely to Tenzin Choejor, Pat Morrow and Colin Monteath. Under the helm of Canadian photojournalist Michael Buckley, This Fragile Planet works to uplift the Tibetan Buddhist environmental, social and, notably, secular ethics that the Dalai Lama has long advanced, most prominently in the public Western eye since winning the 1989 Nobel Prize.

Humanity is entirely responsible for being at the root or the problems that have caused these crises. Which is good news. Because if we have created these problems, it is logical to believe that we have the means to resolve them. The crises facing us today are not inevitable. Ask yourselves: ‘What if fraternity were to be our response to these crises?’

Per its subject’s lead, the publication calls for protection of a country largely obscured from the public eye since Chinese annexation; at the same time, it stresses the global implications of Tibetan environmental decline (as Al Jazeera so clearly intoned in 2015, “Tibet is the canary in the coalmine”). To state just a couple of a plethora of supporting alarming statistics, Tibet is warming at up to three times the pace of the global average. The 2019 IPCC report predicted the disappearance of ⅔ of Tibet’s glaciers within the next 80 years, glaciers which, to name only one utilitarian function, source 10 of the world’s largest rivers. Loss of the glaciers will likely lead to water shortages throughout Eastern Asia, from Tibet to China to India, provoking political strife. 3The Diplomat “The World’s Third Pole Is Melting”

For all of its virtuous volition, however, This Fragile Planet is not a deep-dive into the manifestations of climate crisis in Tibet, nor of its ecological, historical, social and political causes and implications. Buckley’s 2014 Meltdown in Tibet: China’s Relentless Destruction of Ecosystems (2014), or its 2009 companion-film, both of which see the journalist work to document the destruction of Chinese industry on Tibetan soil, are a much surer bet for these purposes. More than informative guide or clear call to concrete action, the publication better serves as both a resting-space and a doorway for the interested reader.

Firstly, the breathtaking photographs comprising the book, particularly those of Tibet, provide a sort of visual respite that at once calms and stresses the urgency of conservation efforts. Secondly, this publication may serve to whet the appetite of readers for more knowledge about the Dalai Lama and Tibet today in a more general sense, potentially opening the doorway for audiences to various recent releases on the subject (see, for instance, Never Forget Tibet, the first in director Jean-Paul Metinez’s tri-part series on the Dalai Lama and Tibetan culture, both traditional and contemporary).

There is a certain comfort to these various glimpses into an essential, day-to-day steadiness with which the Dalai Lama appears to lead his life while carrying the weight of a profound understanding of the gravity of the ecological — and moral — crisis at hand. This Fragile Planet, in its iterative progression from the broad ethics of “Moral Compass” to the specificity of “Preserving the Third Pole” to a “Call to Action” and “Parting Shots,” recalls the oft-used metaphor in models of changing of the seed, as made clear by Buckley’s selection of a line from the Dalai Lama’s 2011 clarion call for secular ethics.

When I am home, I enjoy morning walks and looking at the beautiful flowers in my garden. The row of stout cherry trees at my residence produces exquisite blossoms every year. They are the result of the tiny saplings I brought back from Japan fifty years ago — so they have seen most of my life in exile,

writes the Dalai Lama, referencing expulsion. This Fragile Planet serves to remind that the development of secular ethics, the basis of right response to climate crisis, is a process of cultivation. It requires, diligence, time, care and, in the most bold and generative way possible, faith.

References

- 1Wang, Michelle, 2013. Thousand-armed and Thousand-eyed Avalokiteshvara

- 2Credit here is due largely to Tenzin Choejor, Pat Morrow and Colin Monteath.

- 3The Diplomat “The World’s Third Pole Is Melting”