This article was originally published in The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture & Politics, in the Spring 2022 issue, Rest and Creativity. It is reprinted here with permission.

THE ARROW’S Chief Editor Gabriel Dayley sat down with Kristin Barker, co-founder and director of One Earth Sangha, for a conversation on applying Buddhist teachings to show up with bravery and skill in the face of climate disruption. One Earth Sangha’s mission “is to support humanity in a transformative response to ecological crises based on the insights and practices of the Buddhist tradition.” The conversation explores working with the emotional toll of the climate crisis, understanding how humanity arrived at this juncture through a Buddhist lens, and how we can arouse fierce compassion in the years ahead.

Gabriel Dayley: In your work, you’ve spoken often about the importance of “normalizing our emotional responses” to the climate crisis. Could you say more about what you mean by that and why it’s important?

Kristin Barker: In Buddhism, there is an invitation to pause and begin with our own experience, and to investigate closely what’s happening in our mind and body. This opens us to the potential for wisdom and skillful action, that is, for insight into our present circumstances and for what we can do that will actually be helpful.

At a basic level, we have to recognize the significant emotional challenge presented by the many ecological crises that we’re facing—climate, and also species extinction, ocean acidification, desertification, and others. When we encounter what’s happening and where it all might be headed, it’s not just fear—what we now refer to as “eco-anxiety”—that can arise, but grief, anger, and even despair. While we are all in this terribly difficult situation, it’s hard to share the distress we feel in our hearts; for fear of becoming overwhelmed or making others uncomfortable. Perhaps we’re not sure how to work with these feelings. As a result, we are suffering in silence.

In addition to the emotional impact of knowing the climate crisis is underway, two additional circumstances complicate our experience even further. First, most of us in the Global North enjoy immediate benefits from the harmful system that has created the climate crisis. And let’s face it, we often crave those benefits, right? We like to shop. It feels good when the Amazon package arrives at our doorstep.

The Dharma speaks insightfully to the immense power of craving for pleasure, and how it hijacks our well-being. We can observe this in the world through the ways in which pursuing immediate pleasure subverts our long-term wholeness, damages our sense of meaning and belonging, and decreases our ability to handle difficult situations. And of course, our pursuit of short-term gains is destroying the earth. On top of the overwhelming nature of the crisis, the knowledge that we are participating in, contributing to this destruction provides another reason simply to turn away.

Second, the forces of denial and misinformation about the climate crisis—even when we know better—create confusion and frustration that create a drag on the call for systemic change. The lack of recognition on a significant scale and the absence of effective response can weaken our resolve because we’re not just tackling the scientific reality; we also face widespread complacency and powerful forces seeking to maintain the status quo.

Avoiding the complex emotions around climate disruption has contributed to the incomplete, insufficient, and delayed attention to the crisis in front of us.

The result of these three significant forces—the impulse to turn away from information that is emotionally overwhelming, the desire (for many of us) to maintain a certain lifestyle, and the forceful attempts to minimize, deny and obfuscate our collective impact on the Earth’s living systems—is a situation that grows steadily and painfully worse.

Gabriel: These three forces sound like expressions of what Buddhism describes as the three poisons: passion, aggression, and ignorance.

Kristin: Exactly. And even those who are acting to protect nature are vulnerable to these tendencies. The classic approach to environmental issues has been to say, “People don’t know what’s happening. They don’t recognize the significance of the issue. They don’t understand the physical dangers or moral transgressions that are part of the issue. So let’s educate them, even scare them, so that they get it. Then they’ll act.”

That’s been the approach. And there’s something to that, right? People need to understand the basic facts of what’s happening; otherwise indeed, we won’t act. However, an information-deficit model misses the need to attend to the emotional impact that accompanies such terrifying news. Without welcoming the feelings and attending with compassion, we’re not dealing with the issue, we’re reacting to our own minds.

So, yes, the strategy of, “get the information out there, shake people out of their complacency, get them to see that this is an emergency,” does nothing to address our tangled inner experience.

Gabriel: When we don’t deal directly with the natural emotional reactivity to something so catastrophic, the process of turning away that you describe often seems to involve two extremes of dismissing the issue—one overly optimistic and one doomsday. Either we can “fix” or “save” the climate, which we often hear from Democratic politicians, or we’re doomed to near-term extinction—it will all be over in ten years.

Kristin: Avoiding the complex emotions around climate disruption has contributed to the incomplete, insufficient, and delayed attention to the crisis in front of us. And that has led to these kinds of superficial responses: either, “It’s too late; we’re doomed; it’s all over,” or, “It’s all going to be great; we can fix this; we can save the planet and get back to normal.”

We have to see the way in which the “we can fix this” attitude is actually projecting our own emotional incapacity onto others. This attitude says, “I’m not confident either one of us can face how much is at stake, how unknown this all is, and how hard this might get. So, I’m going to try to avoid all that by saying we have all the solutions that we need, let’s get to work and everything will be fine.”

But the science doesn’t support “we can fix this.” Ecological degradation is inevitable, and it’s going to be painful and costly.1See, for example, the findings of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. While there is still a narrow window of opportunity to prevent the worst of climate change, many harmful effects are inevitable and already impacting us. We’re looking at huge destabilization to societies around the globe, no matter what happens from here. The “we can fix this” attitude simply isn’t honest. But “we can fix this” and “we’re doomed” are not our only choices.

I think it’s important to recognize that these reactions also reflect the fight/flight/freeze response, rooted in our evolutionary biology, when faced with an impending threat or trauma. We can see the flight response in our distractions. We turn to Netflix, our phones, or shopping. The crisis is overwhelming to the system, so we take flight, psychologically. We can see the freeze response in the view, “It’s too late; we’re done for.” It’s a kind of submission. At times freezing is adaptive; if you’re cornered by a predator, staying really still might be a way out. In the case of climate crisis, though, it is a form of giving up—on ourselves, on other people, on society. The fight response is to create an enemy to attack or blame. Like the other responses, this too can be helpful in certain situations. But it’s ultimately not sustainable.

One lesson from research on trauma is that we need to bring ourselves into a window of tolerance.2Daniel J. Siegel, The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are, Third Edition (New York: The Guilford Press, 2020). We need to down-regulate our own systems and co-regulate with each other. If I’m traumatized, part of my response might be to try to traumatize you with how freaked out I am. Whatever my trauma response is, I have this unconscious incentive to recruit you into it so that I have some company in that response. Then I can at least feel the security that we’re all freezing, taking flight, or fighting together, or we’re all just going to party like it’s 1999. I can feel some temporary soothing from that, but it won’t last.

Many of the world’s contemplative traditions have discovered the radical idea of turning towards and connecting with what is difficult in order to down-regulate. This is a magnificent opportunity that makes it possible to say, “it’s unpleasant and uncomfortable, but I can be with what is arising.” As I experience you being with the difficulty, I can start to be with it too. Something signals to me on a somatic level that it is possible for me to be with it. That allows me to begin to calm down. I see you and think, “Gabe is doing okay, and he seems really in touch with this. He’s got some lightness about it. He’s taking it seriously, but he doesn’t seem completely overwhelmed. He’s okay.” That’s the possibility. Unexpectedly, awesomely, I too can handle this. This is being with reality as it is. Neither dooming nor fixing, but stopping and being with what’s here. What’s more, the ability to resonate with our experience is the starting point for action that is truly responsive.

This is being with reality as it is. Neither dooming nor fixing, but stopping and being with what’s here.

Gabriel: You’ve mentioned in your teaching that the buddhadharma also offers a unique perspective on how we got here. Thus far, we’ve been talking about where we are now, and I’m curious to turn to what brought us here, both in the historical sense and in terms of some kind of primordial, collective consciousness. Could you speak about what Buddha’s teachings on duality offer for understanding the origins of climate disruption?

Kristin: Investigation from a Buddhist perspective does offer a unique lens for understanding the origins of the climate crisis. The buddhadharma says that what appears to us as a separate, independent self is actually a fabrication of our mind. That is to say, our self exists in the way that a car exists; what makes a car is a collection of thousands of parts organized in a particular arrangement. If we search carefully, we won’t find any inherent car-ness. If we examine closely through meditation, contemplation, and analysis, Buddhism teaches that we won’t find a solid self “in here” nor a solid world “out there.” Reality is fluid and ever-changing—dependently arising. This is commonly referred to as interdependence. When we believe in, reify, and defend our sense of self, and what we view as the external world, then we solidify reality. We create subject-object duality.

Building on this conceptual mistake—this mis-taking of reality as solid self and other, subject and object—we begin to objectify what we perceive as other. That is, we further reduce what we first mistook as a separate object of our senses into a function, either for me or against me. A tree becomes board feet for harvest. A mountain becomes a repository of coal. When we flatten and objectify that which is subjective, dynamic, multi-dimensional, and ultimately unfathomable, we enable use and abuse. We enable harm. We can do this with trees and mountains as well as individual humans and entire peoples, all according to the function we assign.

What happens when these perceptions accumulate at a collective level, layer upon layer, generation after generation? When they become the stuff of culture and policy? Eventually, some of us amass the power and resources to exploit the phenomenal world on a massive scale. What we are seeing now is the cumulative result of reducing the mysterious, flowing nature of reality down to objects suited to our desires.

Gabriel: To restate this logical development you’re describing, the basic dualism of self and other, or subject and object, that Buddhism identifies turns into objectification, which then facilitates use, abuse, and exploitation. From there, we get acts of violence and violent systems.

Kristin: In the extreme, we get enslavement, war, genocide, the emptying out of our forests, of our oceans, and a global temperature that puts every life and all of life at risk.

Gabriel: Is there an antidote?

Kristin: The first step is to recognize that this is happening. The second step is to re-enchant our relationship with the world, each other, and with ourselves. We have to reclaim a sense of dignity and autonomy and unfathomability that comes before objectification, before solidification.

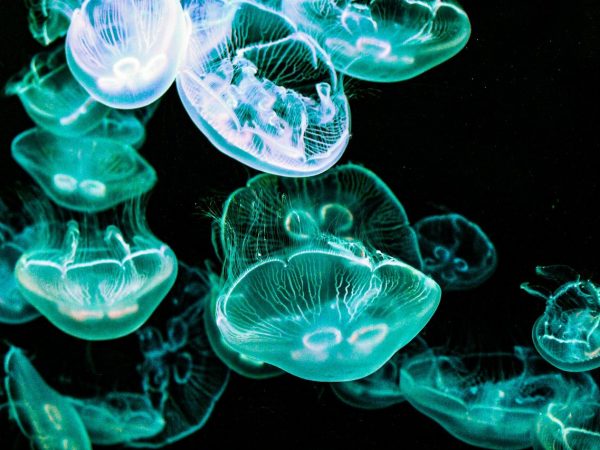

That’s why being in nature can be so helpful to us. The beings we see in nature—the rocks, the creatures, the trees—have a self-existing quality. They’re not just functions for a separate me over here. When we regard these beings as dynamic, unknowable, mysterious, something in us can start to relax. We might start to see ourselves as dynamic, unknowable, and mysterious, too. We come home to a deeper place where we can intuitively sense our belonging in an interdependent web of life. This is part of what it can mean to “re-enchant” our relationships.

Gabriel: Intersubjectivity between subjects, rather than one subject objectifying a perceived other.

Kristin: Yes, intersubjectivity is a beautiful way of putting it. There’s a possibility of reciprocity, and also of restraint. Natural restraint occurs in genuine relationship not because somebody is there to scold me, but because I don’t want to use, abuse, or exploit; I want to participate in an intersubjective relationship. There is a possibility of robust, deep commitment in that type of relationship. My effort to participate in such a relationship becomes meaningful.

In my own life, I find I do things that I know that contribute to climate change or in some way degrade nature. It’s nearly impossible to avoid. How will I respond to such moments? By disassociating, with denial or defensive justification, guilt? What about responding with consciousness, with honoring, with reciprocity? I can minimize harm but when I cause harm, I can consciously honor the taking, perhaps by giving something meaningful and specific in return. So in a moment of taking something from the Earth, driving or buying something that has a negative impact, I might say, “Okay, I am here and I acknowledge harm. I’m going to honor this taking from nature and commit to staying connected, both in my intentions and actions.” With this approach, my aim isn’t innocence or harmlessness, neither of which is possible. But I will minimize harm and honor the harm that I cause. So in this intersubjective relationship, consciousness can lead to both restraint and restoration.

Gabriel: I love how you used the notion of enchantment earlier. For me, enchantment brings to life the notions of reciprocity, relationship, and intersubjectivity. There’s something about re-enchanting that is both a cause and effect of honoring and participating with what appears as “other,” rather than objectifying.

Kristin: Exactly. It’s a way of looking that can bring a great sense of well-being—to the body, to the heart, to the mind—and even mystery.

Just touching the immediacy of the miracle of existence can inspire and sustain us. No matter what happens, we’re part of something incredibly mysterious.

Gabriel: Last question: Responding to the climate crisis is going to require massive systemic transformation if we’re going to make some sort of meaningful impact, whatever that might be. This level of change will require an element of tenacity on our part, in some sense of the word. We can’t just meditate our way into system’s transformation. In your work at One Earth Sangha, you’ve used the phrase “embody fierce compassion.” In your experience, what does that look like in practice? What does it look like to act fiercely while being completely grounded in compassion?

Kristin: Fierce compassion pierces through complacency and the other adaptations of distraction and avoidance. It’s fierce because it breaks the trance of numbness that can be so seductive. Fierce compassion can shake us out of our conditioning to objectify the world. We can deeply consult with ourselves and decide what our lives are going to be about. Then we can ask: what would it look like to embody that? How can our activities contribute to healing the planet or to massive systems transformation, when, of course, there will be frequent setbacks and the outcome isn’t guaranteed?

I can recognize that this crisis has been building for a long, long time, so I can bring lots of compassion. There will be times when I will need to attend to my grief for all the beauty that I see disintegrating before me, or my fear of what else might be lost. I can include all of my emotional responses, as we’ve discussed, and then I can choose an orientation that has a “no regrets” quality to it. I can work repeatedly to contribute to healing, no matter the outcome.

Personally, this orientation is my North Star. I know I have a direction and a dynamic relationship that re-enchants. The compassionate aspect of that relationship acts like warm, nourishing food, and it calls me into more and more devotion. And the fierce aspect pushes me, challenges me, and grounds my efforts. Together, they call me forward into the work.

And then the terrain is the terrain. Like, maybe Congress does nothing. Or maybe another climate denier is elected president. Okay. That might happen. That’s the terrain. I still am devoted. I’m still in relationship with the enchanted world and with that North Star. I will not be stopped no matter what happens. I’m determined to continue to attend to my inner experience, to make sure that I’m regulated, to embody these values as best as I can, and to show up where needed. To contribute in that way is intrinsically meaningful, intrinsically valuable, and not abstract.

We offer, and then we have to let go. Our offering won’t fix everything. It might be really important, or not important at all. How do I even judge that? Let’s get real. We don’t actually know how to evaluate the importance of our efforts. It’s all so mysterious. So, the possibility is to be a grown up, to be mature, to keep inviting connection, wisdom, and skillful action. I think joy comes naturally in that orientation. It moves itself forward. It comes with the territory through that re-enchanting relationship, by reclaiming the sacredness of this amazing world we live in and are part of—planet Earth.

It’s right here, in front of our eyes. It is our eyes, as well as our whole body, this heart, this wonderful mind. Just touching the immediacy of the miracle of existence can inspire and sustain us. No matter what happens, we’re part of something incredibly mysterious. Embodying fierce compassion means fully embracing that mystery, and then showing up for what we love, regardless of the outcome.

The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture & Politics is pleased to offer a 20% discount on all annual subscriptions to the One Earth Sangha community. Subscribe here. Use code ARROWOES in checkout.

References

- 1See, for example, the findings of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. While there is still a narrow window of opportunity to prevent the worst of climate change, many harmful effects are inevitable and already impacting us.

- 2Daniel J. Siegel, The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are, Third Edition (New York: The Guilford Press, 2020).