This is an excerpt of an article originally published in the Fall 2021 Issue of The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture & Politics. The full essay is linked below.

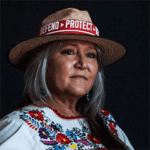

With the chaos that emerges as people attempt to cope with the effects of climate change and the deep inequalities produced by capitalism, structural opportunities and constraints will call for cooperation and collaboration among diverse groups of people.1Peter M. Blau, Structural Contexts of Opportunities, (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994). It is likely that people might increasingly find themselves in contact with people who are from cross-cutting social circles. This means that individuals are members of many different groups, based upon our identities and other traits, and these circles overlap somewhat. Individuals are also members of groups that lie in concentric circles. Thus, each of us shares traits with many individuals, while simultaneously there are many ways in which we are different. Diverse group affiliations and the opportunities for the creation of cross-cutting social circles “provide individuals with multiple social support and thereby free them, at least partly, from oppressive domination by society and its agents as well as by one primary group and its predominant pressures.”2Blau, Structural Contexts of Opportunities, 23. Thus, Winona LaDuke, an Ojibwe writer and activist, is able to describe wind power generation in the Great Plains, utilizing wind power from the local community, financial support from East Coast tribes, and turbines exported from Europe.3Winona LaDuke, Recovering the Sacred: The Power of Naming and Claiming, (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2005). This work to expand wind power is accomplished by a group that is heterogenous across language, class, nation, and race, but shares the goal of carbon neutral power generation and the rejection of the fossil fuel industry and its political power.

While there remain points of conflict between the Indigenous and Settler communities, there are also points of interest that draw people together for the good of their shared environment.

There are other examples of collaborations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to protect the lands and environment. Zoltán Grossman’s work examines collaborative work to save fish, remove dams, respond to fossil fuel extraction projects, stop military land use that leaves behind unexploded ordnance, and seeks to protect communities from the byproducts of mining.4Zoltán Grossman, Unlikely Alliances: Native Nations and White Communities Join to Defend Rural Lands, (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2017). While there remain points of conflict between the Indigenous and Settler communities, there are also points of interest that draw people together for the good of their shared environment.5Grossman, Unlikely Alliances. Grossman identifies instances of cross-cutting social circles, where people share enough in common in spite of their differences, and they are able to build upon those common interests. He notes that when local and state governments sought to stop the Yakama Nation’s work to restore the watershed, the work of landowners then led to federal support. Individuals’ membership or lack of membership in the Yakama tribe did not stop their working together, because they shared other identities and interests.6Grossman, Unlikely Alliances, 117.

Similarly, seeking to clean the toxic chemicals from Onondaga Lake, the Onondaga Nation worked with non-Native allies from the Neighbors of the Onondaga Nation.7Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, 322. Together these groups sought to restore land rights to the Onondaga Nation and specifically required a full cleanup of Onondaga Lake as a part of the conditions of this restoration.8Ibid. Unfortunately, the federal court dismissed the Onondaga’s legal case, but the collaborative work to restore land rights and the health of the Onondaga lake remains an important illustration of how people from cross-cutting social circles can share goals and work together to achieve them.

Because cross-cutting social groups are diverse, the people within the groups are not beholden to one way of thinking; rather, each individual is navigating complex social identities—each person must balance the pressures from the different constituencies to which they belong.9 Blau, Structural Contexts of Opportunities. In this way, disputes are mitigated—each person is working to navigate a balance for themselves and, incidentally, for the group as well.10 Ibid. People belonging to multiple groups with differing opinions and views across the groups are able to see the gray areas and seek to come to consensus in the gray. When we have contact with others unlike ourselves, we adhere less to one particular set of values or beliefs, as we are all pulled in multiple directions by the different groups to which we belong. When we live among people who are different from ourselves, Blau sees us being more likely to approach difference by looking for nuance and understanding, rather than stoking antagonism.11 Ibid.

Indigenous people have a deep understanding of cross-cutting social circles that span human social life as well as the natural world. For example, the norms around marriage and kinship practiced by the Cowlitz people prior to European contact mandated cross-cutting social circles in marital relations. Under strict incest taboos, endogamous marriage was mandated and meant that even distant cousins could not marry.12Iyall, Mike. 2019. Personal communication with the author. As a result, Cowlitz people of the interior prairies of what is today Washington State sought to marry people who lived on the coast of the ocean or even across the Cascade mountains.13Verne F. Ray, Handbook of Cowlitz Indians, (Seattle, WA: Northwest Copy Company,

1966). Endogamous marriage was the norm, and because exogamous relations were very broadly defined, endogamous relationships flourished. The incest taboo creates an enforced system of cross-cutting social circles. Because people were frequently multi-lingual,14Ray, Handbook of Cowlitz Indians. there were fewer social and cultural barriers that we might today confront with marriages of equivalent social and political distance. That this practice was institutionalized shows the value of creating connections across groups, and the importance of having ties across communities.

People belonging to multiple groups with differing opinions and views across the groups are able to see the gray areas and seek to come to consensus in the gray.

In this new world, where capitalism is unchecked and the climate is unpredictable, our intersecting differences create an opportunity for people to discover what they share and work collaboratively to preserve their communities and the wellbeing of all—across class, race, nation, gender, age, and more. With new technologies, our cross-cutting social circles can now be both local and global. In this way we can connect with people around the world to promote new lifeways that are carbon neutral, as Greta Thunberg seeks to do by creating a global movement of children demanding climate action. The choice to strike to gain attention was inspired by the actions of young people from Parkland, Florida who went on strike to protest gun violence.15Jonathan Watts, “Interview: Greta Thunberg, schoolgirl climate change warrior: ‘Some people can let things go. I can’t’,” The Guardian, (accessed March 23, 2019). While all participants in this “school strike for climate” are children, they represent different countries, economic classes, genders, and races, and they speak different languages—but they share a frustration with the inaction of adults and decision-makers on climate action. They work collaboratively both locally and globally to coordinate strikes.

As we do the work to rebuild communities, we all benefit from establishing social spaces that cut across boundaries of class, nationality, neighborhood, culture, and more. Societies that are integrated and interdependent are more likely to conceive of creative solutions to climate change precisely because of their differences in approach and thinking. Valuing creativity, community, inclusion, diversity, and equity, these communities will be better situated to respond to unexpected changes and create desirable outcomes. With technology, our communities can span the globe. Alternatively, we can set aside our technology and deepen our relationships with the people and environment where we live.

Bryan Stanley Turner proposes a model for working collaboratively with diverse groups of individuals via Critical Recognition Theory.16Bryan Stanley Turner, Vulnerability and Human Rights, (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006). In Critical Recognition Theory, people share ideas as equals, hearing each other without judgement, recognizing and respecting others at the same time that they do not take their own positions too seriously.17Ibid. Within our communities, as we build understanding and relationships across our differences, we are also building skills and confidence in working collaboratively. Communities that are interdependent and integrated are better equipped to empower their members to think creatively and confidently, allowing them to propose and enact real changes.

This is an excerpt of an article originally published in the Fall 2021 Issue of The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture & Politics. Continue reading here.

References

- 1Peter M. Blau, Structural Contexts of Opportunities, (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

- 2Blau, Structural Contexts of Opportunities, 23.

- 3Winona LaDuke, Recovering the Sacred: The Power of Naming and Claiming, (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2005).

- 4Zoltán Grossman, Unlikely Alliances: Native Nations and White Communities Join to Defend Rural Lands, (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2017).

- 5Grossman, Unlikely Alliances.

- 6Grossman, Unlikely Alliances, 117.

- 7Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, 322.

- 8Ibid.

- 9Blau, Structural Contexts of Opportunities.

- 10Ibid.

- 11Ibid.

- 12Iyall, Mike. 2019. Personal communication with the author.

- 13Verne F. Ray, Handbook of Cowlitz Indians, (Seattle, WA: Northwest Copy Company,

1966). - 14Ray, Handbook of Cowlitz Indians.

- 15Jonathan Watts, “Interview: Greta Thunberg, schoolgirl climate change warrior: ‘Some people can let things go. I can’t’,” The Guardian, (accessed March 23, 2019).

- 16Bryan Stanley Turner, Vulnerability and Human Rights, (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006).

- 17Ibid.