Highlights

What happens to the land is happening to the person and so that is why Indigenous People so often put their bodies on the line against fossil fuels, mining, all kinds of terrible things that are happening. All of us non-indigenous people, we are born on this Earth. If she’s not healthy, we’re not healthy, so how is it that we don’t put our bodies on the line, how is it that we feel this distance, because ultimately our identity is inseparable. There is not a single element in our body that does not come from the Earth.

If what we feel is that our first obligation is to all the other species, is to protect all the other species, it is to make sure that other species are not harmed, to make sure that the Earth is protected, it means that automatically everything we create is going to be in service of that, it’s going to be in service of a way of living that is sustainable, where we are not harming other things for us to thrive.

A lot of the way I’ve seen Buddhism being transferred in the West is very mercenary, it’s very acquisitive. This capitalist idea that I was talking about where you’re not going to leave anything for anyone else, that has manifested in the way that often Buddhism is spread, which is like, I need to gather everything, I need all of it. But I think there is a way you can practice where you’re true to your own roots and your own identity while really appreciating a different tradition and seeing the best in that tradition and matching their best without denigrating them or without adopting everything and taking it away. So I think for us who are Buddhists in the global South we have the choice, we don’t have to do it that way, we can do it so that we are doing it in solidarity versus consuming.

You don’t have to have access to Nature in this way that we like to imagine, the great Amazon, the Congo Forest, kayaking in the ocean. We don’t need all of these amazing ways, wonderful if you can have it, but like just go within, think about where that oxygen ends for you. How are you not spiritually connected with the Earth? The water we need to survive, the clothes we’re wearing, any amount of product, shoes, house, everything has been given by the Earth. I think first of all we really have to ask ourselves what we mean by Nature when we think about these questions because a lot of the time we have this very idealized idea of nature, it’s Wilderness, and there is a jaguar and it’s far away. We have these ideas and actually Nature is us, we are a species the Earth created that came to be because of all of these conditions on this one planet.

Our commitment to gaining Enlightenment for the sake of all beings is so strong that we’re willing to sacrifice, we’re willing to do our 100,000 prostrations and have bleeding knees because of this Bond, this obligation we feel and we do it so joyfully. I think this is something the environmental movement can learn from religion, that there is a way to sacrifice when it becomes Joy, when we are filled with a kind of an exalted emotion, to do that thing to protect the Earth. If we were to frame it in this way I think there would be something really powerful in our movements, like we’re doing it from a place of joy to protect all life on Earth as opposed to we’re sacrificing our comfort to protect our life on Earth. I think it completely changes how we view things and what we are willing to do.

All of us are addicted to our comfort so we have to find something else that pulls us out of that attachment to comfort. Creating a call to action when you talk about ecodharma, doing it by really emphasizing Dharma principles that are around doing the hard thing with a lot of happiness for the right reason, I think that energy can be very powerful. That is not a teaching that you will find in the scripture. That is actually in the embodiment of how you’re practicing. That is something that each one of you has experienced where you’re filled with bliss no matter how uncomfortable you are. You’re meditating and there are ants in the room and they’re bothering you and you’re still meditating, or mosquitoes are biting you and you’re able to have compassion for a mosquito in that moment. Whatever that discomfort that changed into happiness in your practice, that is not a teaching that is in the scriptures, that is something you’ve experienced. I think that experiential Awakening is what the environmental movement needs and I think that to me is the essence of what ecodharma can bring and do that is different.

I think working with the sacred feminine to talk about our relationship with the Earth could be very powerful regardless of gender because when we are talking about what that experience is like and what that means it really means letting go of ego, without anger and without even rejection. What is there when we let ego go? Everyone else is there, everyone that we ignored is there, every person that is as special as us is there. I think that means that we get to put the context of our human species within all the two million species that are out there. So we can let go even of our species ego and have this deeper dialogue around the diversity that exists, the fact that there is not a species that exists without purpose on this planet.

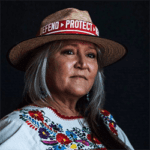

This interview was primarily aimed at Dharmadatta’s Latin American community and you can also watch this in Spanish on faceBuda, their Spanish-language YouTube channel here.