As a child, I grew up with strong feelings

Deep feelings of who I am and what is important in life

I felt one with the world

Living and caring was one

As I became older, culture took over

The stories I heard began to color my life

I went to school

I learned that adults and experts know—not children

I learned that knowledge is external—not internal

Kicked out of the world of wonders and wisdom

I started filling up my brain with knowledge to find a new place in the world

I went through academia

Learned that the truth is complicated

Learned to express myself in complicated ways

Over time, I started to not understand myself anymore

Hiding myself under layers and layers of “othering” to feel protected

At one point, my heart and body became rebellious

My voice refused to repeat others’ stories

My thoughts refused to ignore my feelings

Feelings of partiality, imperfection… of separation

I lost my voice

It’s when I saw the separation in the world

Consumerism, injustice, climate change

It’s me. It’s us. It’s one story

Searching for a new voice is scary

It makes me shiver

And there is a strong headwind out there

But if you understand my silence, you may understand my words

Delving into stillness, you may hear my call

After many years of working in the field of sustainability, I became more and more aware that we are neglecting one important part of the story: our minds, our inner lives, and our inner capacities. How could we have come to this point?

Today’s society is characterized by increasingly complex sustainability challenges, notably climate change and its impacts on biodiversity, food, energy, water, and human health. We urgently need to find better ways to sustainably address climate change. Without additional efforts and measures, there will be catastrophic, irreversible impacts globally. It’s clear that—despite the high profile of sustainability as a concept, and the goals and targets that have been set since the 1980s—the dominant approaches have not catalyzed the necessary change.

Our professional and technological capabilities have been increasing exponentially, but our ability to use them wisely has not. We are building vast, complex civilizations, but that very complexity is in danger of overwhelming us, creating huge and unintended consequences for the planet and all those that inhabit it.

Our minds influence not only our personal, but also our collective story, and they are key to creating a more sustainable future.

One important reason for the current situation is that the vast majority of sustainability scholarship, education, and practice has, so far, only focused on the external world: ecosystems, socio-economic structures, and technology. Much of this work originates from modern societies’ mechanistic paradigm and the associated biophysical discourse, which frames climate change as an external, technical problem. This view drives the nature of our actions.

In search of solutions, I naively set out to explore sustainability from not only an external, but also an internal lens. I dared to ask if and why our mind, and innate capacities, such as mindfulness and compassion, could play a role. I wanted to establish a platform for related research, education, and networking.

The first responses were blunt: this would be a career-ending move. Only later did I understand that these responses lay at the very foundation of the question I was asking. Nonetheless, I found comfort in advice to not expect applause if I rattle the system.

Climate Change as Relationship Crisis

I threw myself out there, into the humility of Not Knowing. What do our minds have to do with the climate crisis?

According to my explorations, quite a lot. Our minds influence not only our personal, but also our collective story, and they are key to creating a more sustainable future.

In short, my work shows that the mind is: 1) a victim of increasing climate impacts, 2) a barrier to adequate climate action, and 3) a key driver, or root cause, of the climate crisis, as it determines how we relate to ourselves, others, and nature. The net result is a vicious cycle of deteriorating individual, collective, and planetary well-being.

Effective climate action thus demands that we understand the vicious cycle of mind and climate change and comprehend it as a crisis of relationships. This allows us to actively consider the role of the mind in stemming this existential threat.

The Mind as a Victim of Climate Change

Our minds are a victim of escalating climate impacts, leading to a vast increase in climate anxiety across society. One of the first things I generally hear when talking to politicians working in sustainability is the number of people who are feeling anxiety, or fear, as a result of the ecological collapse, and the projections that we’re currently looking at. Many observe that there has been a considerable increase in eco-anxiety, climate grief, and associated overwhelm in today’s society, particularly among younger generations.

Many people perceive that the most devastating climate change impacts relate to mental health and stress: constant feelings of uncertainty and unpredictability, fears about personal safety, traumatic experiences, and losing a sense of identity, meaning, and hope. This results in long-term societal implications, such as increasing drug abuse, interpersonal aggression, violence, crime, polarization, and extremism.

Today, the world economy has become the ‘end,’ and nature and humans have become the ‘means,’ the resources for the economy.

Negative mental impacts can also result from the way people (non-)engage with climate change. Many feel that the issue is too big. They feel powerless. They can’t sleep. This can, in turn, lead to denial or guilt about not doing enough, even among those who engage, until they burn out.

Finally, there are more indirect mental health impacts of the underlying social paradigms that drive climate change. In fact, depression and anxiety have much to do with the current way of life in modern societies, and how it fails to meet our mental health needs. I elaborate on this aspect later in more detail.

The Mind as a Barrier for Adequate Climate Action

The mind is not only a victim of climate change. It is also a barrier to climate action, creating obstacles to necessary change and action-taking. We are often our own worst enemy when it comes to making change happen.

Relevant processes emerge from our habits of mind, including cognitive bias, default “autopilot” mode, and threat responses. Cognitive bias often results from our mind’s attempt to simplify information processing, and to maintain an energy-saving autopilot mode, thus affecting the climate-related decisions and actions that we take. In-group bias (or us-versus-them thinking) is a concrete example. We tend to treat those we deem as outgroups as if they are incidental, in our way. We lack compassion for those we place in outgroups, losing the ability to care about them. We do this not just towards human beings but also towards other species.

In addition, cognitive biases and distortions make changing habits challenging. Polarized thinking (polarization effect, confirmation bias), short-term thinking (hyperbolic discounting bias), and a tendency to blame or rely on others and not take responsibility for action (bystander effect), all contribute to a lack of agency and care—leading to adverse reactions, including blaming others, feeling powerless against the magnitude of the problem, or denying the problem.

Our nervous system’s fight-flight-freeze response reinforces these effects. It’s our mind’s natural reaction to perceived threats, and can be induced by individual, societal, and environmental factors. When we are in a fight-flight-freeze mindset (e.g., high sympathetic nervous system arousal), we are less empathetic, it can make us more prone to extremist views, and more prone to pronounced in-group bias and us-and-them dynamics. All of this ultimately reduces the political space for collective action on shared problems—above all, climate change.

The issue of denial also relates to other mental experiences. The climate crisis is the ultimate existential crisis. People don’t like to be anxious, and the avoidance of anxiety leads to denial. We want to look away, and sadly in this denial we continue business as usual, which not only reinforces the problem, but makes the problem irreversible.

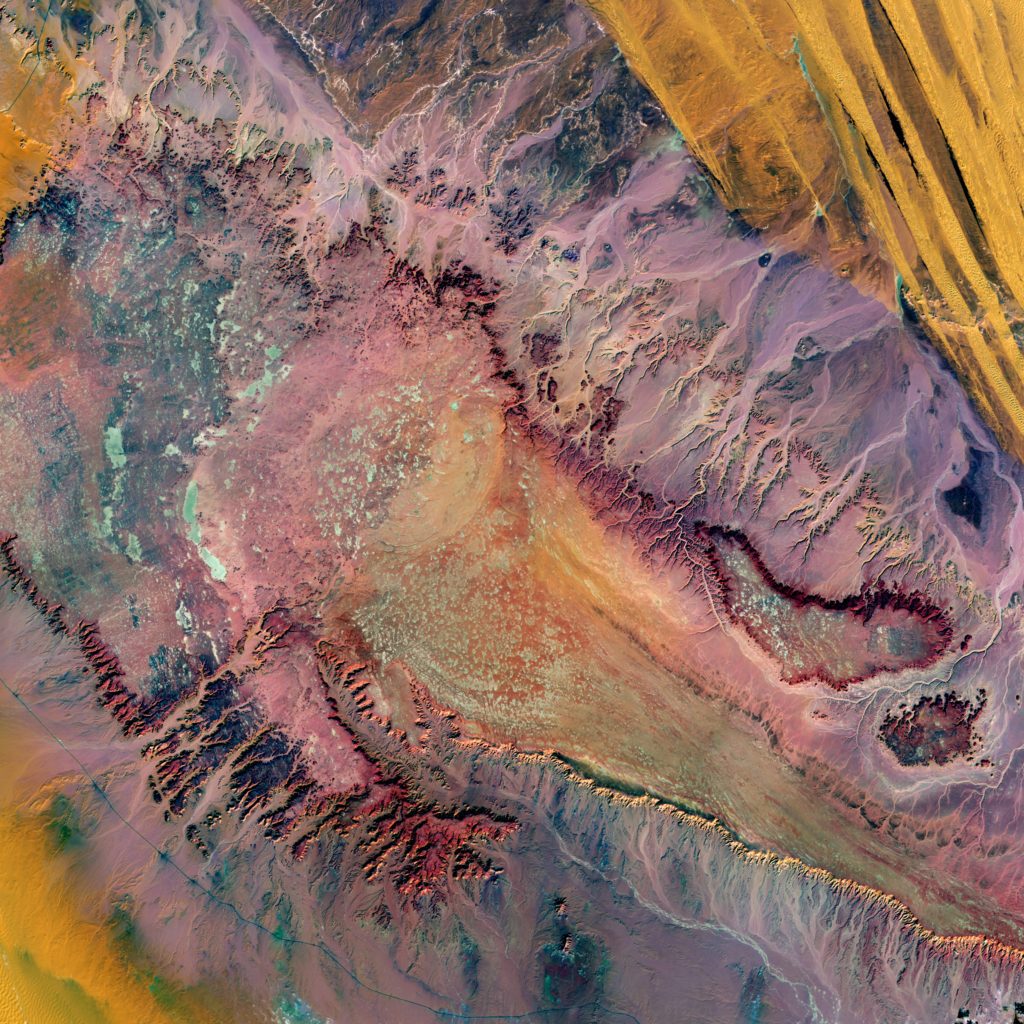

The Mind as a Root Cause of Climate Change

Importantly, the mind is also a key driver, or root cause, of the climate crisis; it lies at the heart of the catastrophic changes we’ve enabled. Today, we increasingly understand that climate change and other sustainability challenges are internal, relationship crises. They result from modern societies’ story of separation. This story assumes that we are all separate from each other, that some humans are superior to other humans, and that human beings are both separate and superior to the rest of the natural world. Our society is rooted in this social paradigm of separation, which plays out in our institutional and political structures. In its most extreme form, it manifests as war, racism, classism, sexism, and exploitation, which relate to issues such as economic or territorial gains, or nationalism.

In a world designed for attentional hijack, mindfulness can help us regain power over the content of our minds.

Social paradigms are a vital part of society because they present cultural information that is passed from generation to generation. This information guides our behavior and expectations. In all areas of life—be it politics, research, or practice—social paradigms influence how problems are defined and addressed, including what is considered realistic, legitimate, and effective. Paradigms impact every level of existence: from the micro at the private level; to the meso and macro at the public level; to the mundo at the global level.

In the modern world, we follow what can be called the mechanistic paradigm. The mechanistic paradigm, which is considered endemic to Western civilization, is based on a fundamentally dualist and atomistic view of life that values individualism and independence above all. Systems are reduced to their constituent parts and analyzed in terms of mechanical interactions. Nature is understood to be an object—a resource—for people to exploit. The capacity to shape the world through technology underpins notions of progress, creating a culture of individualism and industriousness.

The story of separation can be vividly seen in the human-nature divide. Treating the environment as a resource that should be used for the benefit of humankind has ultimately led to its abuse and destruction. Today, the world economy has become the ‘end,’ and nature and humans have become the ‘means,’ the resources for the economy. Believing ourselves to be separate and superior has severe consequences for sustainability. Such thinking supports the idea that we can use limitless natural resources to feed material prosperity, and an unquestioned principle of consumption.

Climate change can thus be understood as an outward manifestation of our exploitative minds, which are, in turn, rooted in a disconnect with ourselves (thoughts, emotions, bodies), others, and nature. Our minds shape, and are shaped by, the dominant social paradigms—economic growth and associated consumerism, materialism, competition, and individualism. The dominant model of economic development has no regard for the impact of its activity on nature and living beings, treating them largely as factors of production.

This shows the interconnection of our individual and collective minds and the systems we live in. It also shows that climate change is a symptom of an inner crisis—a relationship crisis—which is intrinsically connected to other societal challenges such as social injustice and political conflict.

The awareness that our mind is at the heart of the climate crisis is relatively low compared to the other aspects (mind as a victim and barrier). This stems, in part, from the fact that our institutions, communities, and networks, and the way we think about these issues, are predicated on an immutable wall between inner and outer.

It is the manifestation of generations of exploitative mental habits that have got us to this point. This is also what made it challenging for me, personally, when I embarked on bringing these two worlds together.

The Mind and Climate Change: A Vicious Cycle

The relationship between mind and climate change is not linear, but complex and entangled. It forms feedback loops that degrade personal and planetary well-being. As much as our mind is driving climate change, climate change is driving negative mental health, fear, and denial, which in turn exacerbate our unsustainable responses at the individual and collective levels.

In its simplest form, this vicious cycle manifests in the following way: The state of the climate impacts our mental health. As a consequence, reflecting the modern growth paradigm, we may go shopping to make us feel better, with direct implications for unsustainable consumption and climate change.

Mindfulness … makes it possible to turn towards distress rather than shutting down, and helps develop the resilience necessary to cope in situations of profound difficulty.

But there are many other facets of this vicious cycle. Climate change-related uncertainty creates anxiety, which we commonly deal with through avoidance that only further increases anxiety and unsustainable coping mechanisms. This anxiety creates a feedback loop that becomes self-reinforcing. In addition, stress and fight-flight-freeze responses to perceived threats reduce empathy and compassion and foster in-group bias and polarization, impeding social cohesion and the collective action needed to address climate change, while fostering unsustainable coping and habits that spur it. The latter is reinforced by long-term stress, leading to reduced self-reflection and creativity. Furthermore, the social paradigms and associated mindsets that are at the root of climate change undermine well-being and foster fears and habits of mind that, in turn, keep those paradigms and mindsets alive. For example, the worldviews of materialism and individualism can create socialized fears based on internalized cultural messages of separation, which can increase anxiety, trauma, depression, cognitive biases, and foster inequitable systems.

Breaking the Cycle

Understanding the intersection between mind and climate change shows that sustainability crises are inherently about how we relate to ourselves, others, and the environment. Changing the way we engage with each of these relationships can help bend our story towards a more sustainable path. This applies not just to individuals, but to all groups and organizations, including governmental and private institutions.

Regrettably, in today’s world, the relationship between mind and climate change is not addressed in mainstream climate policy and policymaking approaches, which, consequently, fail. Instead, they operate within the same collective mindset that created the climate crisis in the first place, thereby perpetuating the vicious cycle.

Humans possess the capacity for deep conscious connection with ourselves, with others, and with nature. But in our current institutional and political landscape, the qualities that serve these relationships are often deprioritized, underdeveloped, and neglected.

Tracing the roots of the climate crisis through a culturally entrenched story of separateness, we can see the potential of mindfulness and compassion, as they can foster fundamental aspects of connection, and thus revert from a vicious to a virtuous cycle of mind and climate change. While more research is needed, there is increasing scientific evidence for this. In a world designed for attentional hijack, mindfulness can help us regain power over the content of our minds. It makes it possible to turn towards distress rather than shutting down, and helps develop the resilience necessary to cope in situations of profound difficulty. It can help us relate to experience just as it is—remaining connected to unfamiliar or challenging information and shifting perspective to hold a greater range of possible understanding. It also helps to cultivate respect for bodily sensation as an arena of knowledge, which broadens the scope of understanding available to us in relating to and addressing our collective challenges.

But connection with the realities of the climate crisis necessitates not only the management of negative impacts. It also requires supporting positive emotions of social connection, human-nature connection, agency, care, hope, and courage that are critical in collective response to the climate crisis. Mindfulness and compassion practices can nourish related capacities.

Mindfulness and compassion influence the inner lens through which we see the world and our identity within it. They do not merely soothe the inner symptoms of individuals beset by crisis but can support us to engage together to transform unsustainable societal structures. They help us stay in touch with our inner lives and what matters to us most, and realign intention with what others and the world needs. In doing so, they can also help us to step out of undesirable behavior patterns, supporting us to act consciously and creatively in the face of increasing sustainability crises.

Even so, mindfulness and compassion training can serve to reinforce the story of separation, if they are designed as an individual practice that benefits resilience in a modern capitalist world. It is essential to change this narrative. We need to decolonize our minds. We must examine how we have internalized deep cultural messages of separation, superiority, and instrumentalization, and develop alternative approaches rooted in a sense of interconnectedness.

Our influence is broader than we realize … and intrinsically linked to collective and systems change.

Thought patterns and mental structures are not personal: we internalize the values, norms, and messages present in our culture. If we examine our habitual thinking, we can begin to see how we have internalized many of these patterns and assumptions. We can have profound impacts when we let go of mental habits, decolonize our minds, and begin to question how the paradigm of separation is maintained.

You Matter – Everyone Matters

How we think and act in the world matters a great deal. Social network analysis shows that what we do not only affects our friends, but also our friends’ friends’ friends. It even affects people we do not know. The chances that an individual will vote increases if that individual’s friends’ friends’ friends vote, and vice versa. Our influence is broader than we realize, and complexity theory, quantum social sciences, and inner-outer transformation models show that this influence is deeply complex and far-reaching, and intrinsically linked to collective and systems change.

Social network analysis and climate mainstreaming theory also provide insights into how we can best create the conditions for a new story to emerge, showing how we can spread our ideas and understanding within groups and organizations. For instance, ideas circulate and are shared most effectively in groups where a few people know each other, and where there is a continuous influx of new members, bringing new ideas and new connections. These kinds of groups are a powerful platform for ideas to spread.

In addition, mainstreaming the consideration of the mind and inner capacities in all sector work must be approached in the same way as we have addressed mainstreaming other issues (such as climate policy integration or gender mainstreaming), that is: through the systematic revision of organizations’ vision statements, communication and project management tools, working structures, policies, regulations, human and financial resource allocation, and collaboration. It goes far beyond merely offering capacity programs.

Conclusions

Evidence increasingly shows that climate change and other sustainability challenges are, in fact, internal relationship crises, and that the potential of our minds, mindfulness, and compassion in stemming the climate crisis comes from their potential to foster fundamental aspects of connection.

Whether we seek to understand the source of sustainability challenges like climate change; to shift the paradigms, systems, and behaviors that drive it; or to nurture capacities that we will need as stewards of an uncertain future; mindfulness and compassion can form an essential foundation. Delving into stillness, we might discover that the pathways to sustained individual, collective, and planetary well-being are intrinsically interlinked.

Delving into stillness, we might discover that the pathways to sustained individual, collective, and planetary well-being are intrinsically interlinked.

From an ethical standpoint, it is important to highlight that an increased consideration of the mind in climate work is not about saying we need to change people’s beliefs, values, and worldviews. This would turn people into objects to be changed rather than seeing them as change agents. The former risks co-opting the concept of sustainability and transformation to preserve business-as-usual through a ‘fix-it’ and ‘fix-others’ mentality that reinforces current, unsustainable paradigms. It is this kind of thinking that has led to modern societies’ focus on technical solutions and behavioral changes, while ignoring systemic factors and the underlying causes of today’s sustainability crises.

Instead, we need to support learning environments and practices that help us discover our internalized cultural patterns of being, thinking, and acting, and increase our sense of purpose and interconnection. This can help us to let go of habits that are an expression of the narrative of separation, and understand well-being and sustainability as qualities we can nurture. Yet this alone is not enough.

We also need to systematically mainstream the consideration of the mind in existing systems and structures of our current political and institutional landscape, thus creating the conditions for a new, more sustainable story to emerge.

We have to rattle the system and resist the persistent either/or thinking in our modern culture and approaches to climate change, because:

The true system, the real system, is our present construction of systematic thought itself, rationality itself, and if a factory is torn down but the rationality which produced it is left standing, then that rationality will simply produce another factory. If a revolution destroys a systematic government, but the systematic patterns of thought that produced that government are left intact, then those patterns will repeat themselves in the succeeding government. There’s so much talk about the system. And so little understanding. 1Pirsig, R. (1974) Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Mariner Books. [Freely available online]

Actions that challenge the status quo and help us to break out of our internalized patterns and structures are thus crucial to move from a vicious cycle of mind and climate change to a virtuous cycle of personal, collective, and planetary well-being and flourishing.

This essay is based on the following publications and initiatives:

Bristow, J., Bell, R., Wamsler, C. (2022) Reconnection – Meeting the climate crisis inside-out. Policy report, The Mindfulness Initiative & LUCSUS [PDF].

Wamsler, C., Bristow, J. (2022) At the intersection of mind and climate change: Integrating inner dimensions of climate change into policymaking and practice, Climatic Change 173(7). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03398-9

Wamsler, C., Osberg, G., Osika, W., Hendersson, H., Mundaca, L. (2021) Linking internal and external transformation for sustainability and climate action: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Global Environmental Change, 71:102373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102373

Wamsler, C. (2018) Mind the gap: The role of mindfulness in adapting to increasing risk and climate change. Sustainability Science, 13(4):1121-1135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0524-3

Wamsler, C., Brossmann, J., Hendersson, H., Kristjansdottir, R., McDonald, C. and Scarampi, P. (2018) Mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, and teaching, Sustainability Science, 13(1):143-162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0428-2

The Contemplative Sustainable Futures Program.

Several Medium articles.

This essay first appeared in Insights: Journey into the Heart of Contemplative Science and is reproduced with permission from the Mind & Life Institute.

References

- 1Pirsig, R. (1974) Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Mariner Books. [Freely available online]