The steady flow of minerals from Tibet’s sacred mountains to global markets is haunted by the ghost of Canadian mining companies.

In the Chinese-occupied nation, Canadian companies were among the first to gain access to the copper, gold, lead and zinc under its peaks—making Canada, for a time, a major foreign investor in Tibet.

Over the last decade and half, they built roads, constructed hydro dams, laid railways, and hollowed out mountains.

But today, all but one of the original dozen Canadian corporations that made their presence felt have sold off their projects.

Their exodus, often in the wake of community conflicts, opened the door to Chinese-owned companies. With the sale of their projects and technology transfer to the Chinese government, Canadian companies served as a surrogate helping Beijing create an industry they could not themselves have birthed.

With the sale of their projects and

technology transfer to the Chinese

government, Canadian companies served

as a surrogate helping Beijing create

an industry they could not themselves

have birthed.

Now China is cashing in.

“Canadian mining companies were burned,” said Tsering Shakya, a historian of modern Tibet at the University of British Columbia. According to Shakya, China knows how to entice capital, but once it was convenient to do so, it shook off foreign control.

In the process, Tibet’s people have paid the highest price.

Protests against mining have been one part of a wider resistance movement to Chinese rule. Since 2009, that resistance has made itself felt through 169 acts of self-immolation, by monks, workers, nomads, and other ordinary Tibetans.

Tapping into hundreds of millions of tons of mineral resources is central to China’s long-term plans for Tibet. And while Canadian mining companies did not start the Chinese dispossession of Tibet, their technical knowledge and capital has helped hasten its pace and scale.

Prying open Tibet

In Tibetan culture, mountains contain gods and spirits that should not be disturbed. But that has done little to deter western or Chinese mining developments.

“‘There’s a lot of interest in Tibet from miners,” a mining claim broker told Reuters in 2008. “It’s one of the few virgin territories left in China.”

Early attempts at mining in Tibet by Chinese companies—notorious for their use of Tibetan prison labor—aimed to meet local economic needs. But these companies, owned by Chinese state officials, did not have the ability to fully exploit the rich veins of minerals.

For the industry to advance, it needed rail access and power grids, and improved technology.

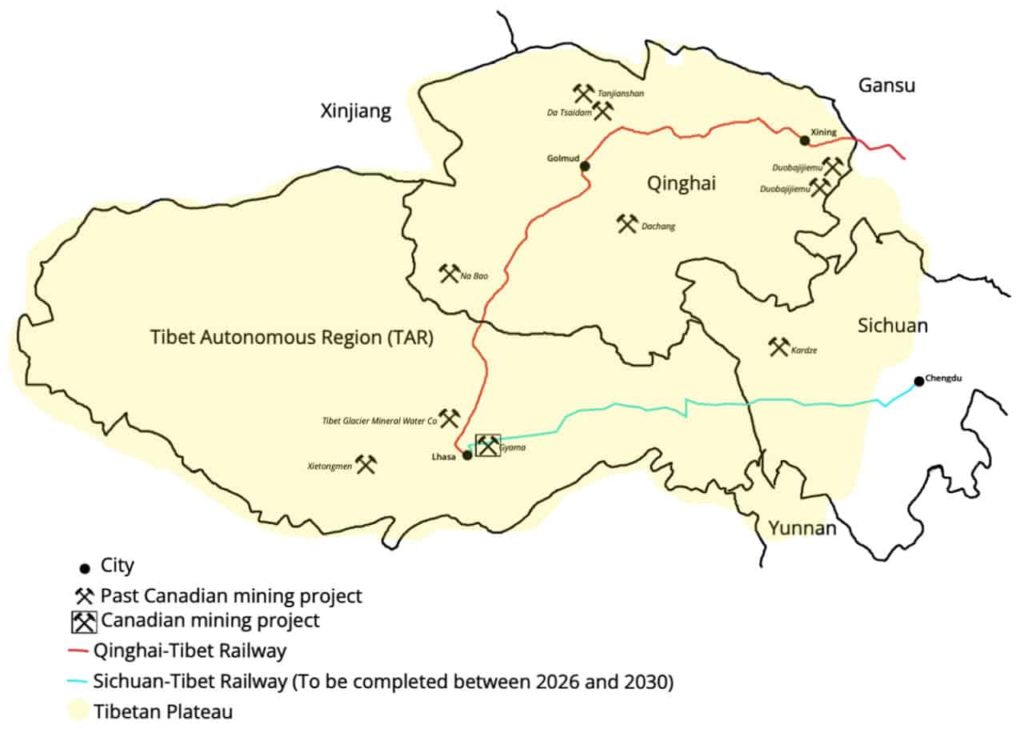

Canadian exploration companies arrived in Tibet in the early 2000s, marking the beginning of a mining boom. It was Canadian “minnows”—smaller mining companies, as distinguished from “majors”—that provided know-how, with engineering firms from Toronto and Montreal providing key hydroelectric technology.

Canadian involvement was “crucial in transitioning China from small-scale, state-controlled extraction to world-scale, faster and more intensive extraction,” Gabriel Laffitte, an independent researcher that studies Chinese policy on the Tibetan plateau, told The Breach.

Extraction prior was “labour-intensive rather than capital-intensive and tech-intensive,” explained Lafitte.

Tibetans are largely in unison when it comes to resistance to mining and ecological harm.

“The Chinese literally scraped the surface, seldom having the capital to go underground,” he said. The process effectively ruined many deposits that, according to Lafitte, could have been mined in a planned, integrated fashion, over a much longer period.

It was Canadian minnows, specialized in drilling and mapping out ore deposits for efficient extraction, that showed how to go after more than one type of ore, reducing wasted rock.

Mines couldn’t operate in Tibet at the next level without a hand from top Canadian engineering firms, and the technologies developed by other Canadian companies.

SNC Lavalin helped build the hydroelectric dams that power many remote mining and refining operations, while telecommunications firms like Nortel chipped in with wireless infrastructure.

Bombardier provided high-altitude railcars for the Qinghai-Tibet railway, which reached the administrative capital of Tibet, Lhasa, in 2006.

The same technology is being used for the $50-billion Sichuan-Tibet rail line. Once completed, the massive project will massively reduce the travel time between provincial capitals Chengdu and Lhasa, making Tibet more accessible than ever to Chinese mineral supply chains.

When the new railway goes online in 2030, many expect a new explosion in mining for lithium, a key component for batteries used by electric vehicles.

Canadian companies, Chinese coercion

Tibetan resistance to the Chinese rule has varied—with the Tibetan government-in-exile, the diaspora in India, and US-funded groups abroad all adopting different strategies—and their demands have ranged from calling for language rights to restored access to pastureland, from increased religious freedom to the return of the Dalai Lama, and from separation from China to partial autonomy within it.

But Tibetans are largely in unison when it comes to resistance to mining and ecological harm.

Throughout the years of Canadian mining, their operations drew protests, with reports of nearly two dozen large-scale protests between 2009 to 2014—to which Chinese state forces have regularly responded with violence.

Tibetans held public demonstrations, staged sit-ins, blockaded mines, and even burned themselves to death.

In 2009, locals protested the theft of water by the Huatailong mine, owned by Vancouver based China International Gold Resources. After the protests, Chinese riot police vehicles patrolled the area, with several villagers being arrested and held for up to a year in prison. That mine remains the sole operation run by a Canadian company.

Protests against mining have continued even after ownership began to change hands to the Chinese.

Throughout the years of Canadian mining, their operations drew protests … to which Chinese state forces have regularly responded with violence.

Continental Minerals, a Canadian subsidiary of global Vancouver mining group Hunter-Dickinson, had been exploring a copper and gold site 240 km south of Lhasa. Two months after its sale to Chinese state-owned enterprises in 2010, hundreds of locals gathered to interrupt its operations.

The protestors stopped further work from being carried out at the site, occupying it for a full month, but were removed by armed Chinese police, with several receiving prison sentences.

Since widespread riots in 2008 in the lead up to and in the aftermath of the Olympics being hosted in China, the Chinese security state has heightened its presence in Tibet with increased police, highway checkpoints, and surveillance of political activities.

With most avenues to dissent being blocked, self-immolation became a prevailing mode of protest.

In 2012, Tsering Dhondup, a 35 year old nomad and farmer who was a father of three, self-immolated at the site of a mine in Amchok, Sangchu county. Six days later, 18 year old Kunchok Tsering did the same.

Canada cashes out, China cashes in

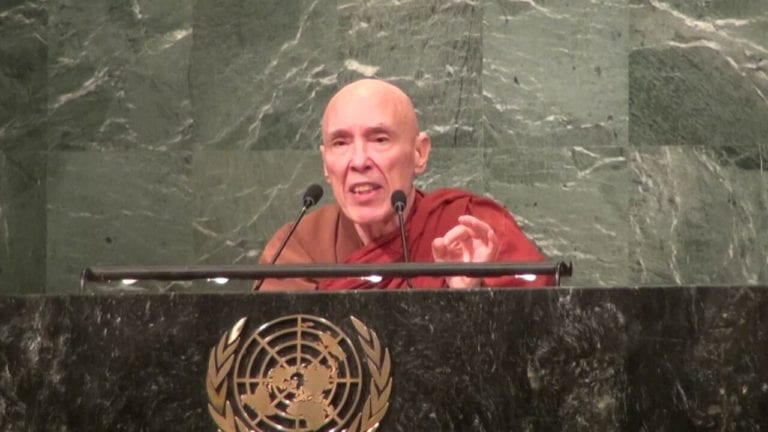

In an interview with The Breach, Ron Thiessen, CEO of Hunter-Dickinson, sketched out the transition away from Canadian-dominated industry in Tibet.

As Chinese state-owned companies began competing for places on his board and eventual ownership of his mine, Thiessen says that a representative from the company who eventually bought it compared the Canadian company to a “rich husband” and the competing Chinese companies to an “original wife” and a “new concubine.”

According to Thiessen, China’s Minister of Land and Resources had expressed initial enthusiasm for foreign companies, because state-owned enterprises were harder to control.

“State-Owned-Enterprises often ignore directives,” said Thiessen. Canada’s minnows, on the other hand, established efficient new operations.

But within a few years, new permits began stalling and Thiessen turned to making a sale. He expressed disappointment that he was never able to study the full potential of the company’s exploration rights.

But Laffitte notes that minnows still made a handsome profit on their own terms.

Continental’s mine sold for $432 million, at the time it was the largest asset sale in Hunter Dickinson’s history.

In 2016, Vancouver-based Eldorado Gold Corp sold a mine in Tibet, along with two other mines in China, for $600 million, well over their market valuation.

UBC professor Shakya says it’s important to consider China’s mineral wealth development in a wider context.

“Activists talk about Tibet being rich in mineral resources and that being why China wanted to develop infrastructure,” said Shakya. “China does have a policy of resource independence, but mineral wealth does not solely explain why China is developing such costly infrastructure”

Rather, he says, the development of infrastructure in Tibet is part of Chinese integration of Tibet. Seen this way, the physical integration by way of roads, rail, and air travel, has brought Tibet into China’s physical logistics network.

And none of it would have been possible without the participation of Canadian mining and engineering firms.

“In the past, Chinese leaders would travel from Beijing to Calcutta to get to Tibet’s Lhasa,” said Shakya. “Now the route is much more direct.”

This article was originally published by The Breach. It is reprinted here with permission.