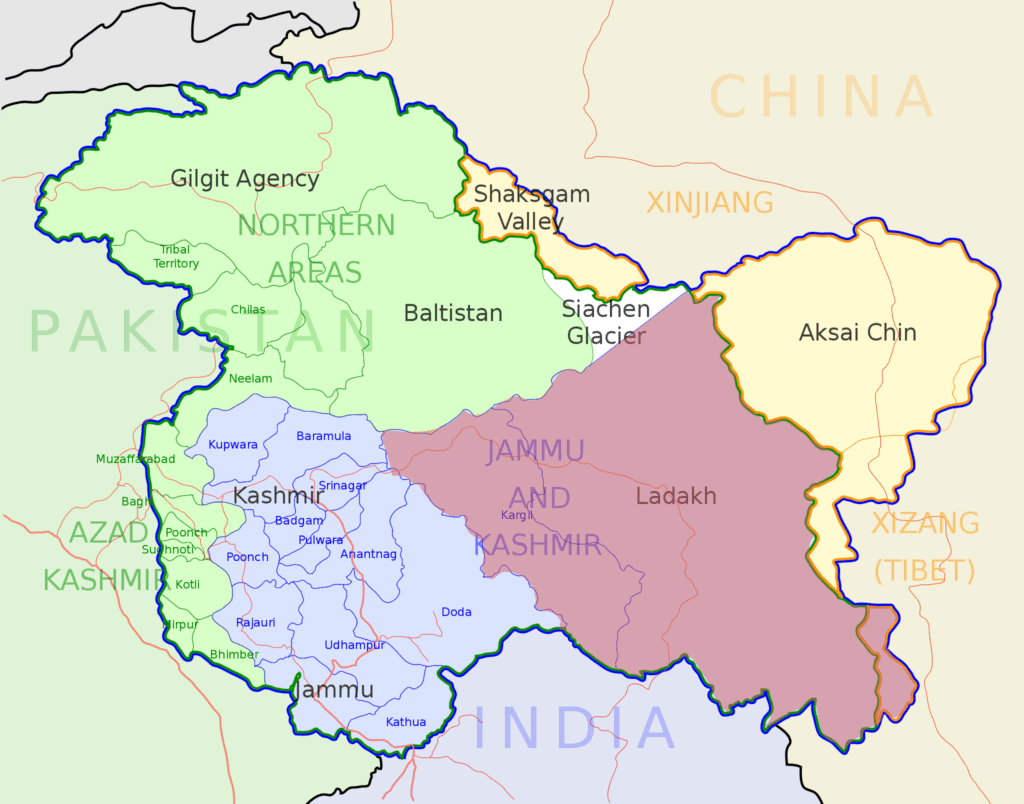

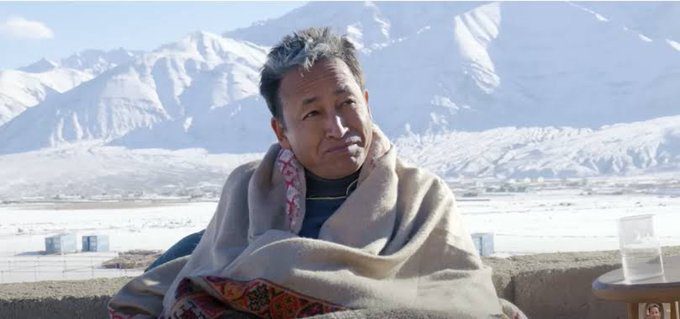

In India’s northern territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, a movement of religious leaders and citizens demanding statehood and greater control of the environment is growing. Residents there, led in part by 56-year-old Buddhist engineer and innovator Sonam Wangchuk, are demanding democratic rights for their region, which has been subject to strife since India’s independence in 1947.

Wangchuk held a five-day hunger strike on 26 January, in a remote desert in Ladakh. In doing so, he drew together Buddhists and Muslims in the region who had been divided for more than 60 years. This division began, in part, in 1947 during the partition of India into India and Pakistan. At that time, Buddhist-majority Ladakh was made part of the larger Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir. Subsequent unrest between Pakistan and India, as well as posturing in the region by China, led to ongoing distrust between the two religious communities.

Our protest isn’t just political … It is for safeguarding our lands, culture, local languages and environment.

In 2019, the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, led by Narendra Modi, moved to revoke Jammu and Kashmir’s special status as a state. In its place, they created two union territories: the territory of Jammu and Kashmir and the territory of Ladakh. At first, Buddhists in Ladakh celebrated the change, hoping that it would lead to greater autonomy. However, actions by India’s government soon caused concern among the residents of Ladakh.

Chering Dorge, former BJP president in Ladakh, told reporters in 2020 that almost immediately, control over local affairs was stripped from the locally elected council. He also expressed concern that state “land may be transferred to industrialists or the army without the consent of the council.” 1Al Jazeera, Ladakh Buddhists who hailed India’s Kashmir move not so sure now

Amid the concerns, protests began across the region as early as 2019, but Sonam Wangchuk has acted to bring the disparate factions together into a unified concern for local control and protection of the environment.

“Our protest isn’t just political,” noted Sajjad Kargili, a social activist from Ladakh’s Muslim-majority Kargil region. “It is for safeguarding our lands, culture, local languages and environment.” 2Religion News Service, In remote Himalayan desert, Buddhists, Muslims, Christians unite to protect land, heritage

Leading the protest movement is a coalition of religious leaders known as the Leh Apex Body and Kargil Democratic Alliance—both of which are made of a mix of social, political, and religious leaders.

According to Feroz Khan, a leader in the Kargil Democratic Alliance, “Faith leaders are trusted more than political parties” in the region. 3Ibid.

These groups rarely have input into the projects that could deeply affect them.

Central to the concerns of local residents are planned large developments and industrial projects, including seven hydropower dams and a large solar energy plant slated for an environmentally sensitive area.

Social activist and member of the Leh Apex Body, Jigmat Paljor, said: “We are not against development, but these projects should not be at the cost of livestock and the livelihoods of nomadic people.” 4Ibid.

These concerns are based on worries about the overwhelmingly rural and tribal make-up of Ladakh’s populations. These groups rarely have input into the projects that could deeply affect them.

Wangchuk’s hunger-strike helped to unite people across Ladakh’s small towns and villages. Buddhists in these rural areas coordinated symbolic retreats to show solidarity during periods of of his hunger-strike.

“On the last day of his fast, Buddhist monks led prayers at the Chokhang Vihara Temple where over 500 devotees had congregated,” said the vice president of the Ladakh Buddhist Association, Chering Dorjay Lakrook. “All the Buddhist monks were supporting Wangchuk’s protest.” 5Ibid.

In February, political and religious leaders from Ladakh held a demonstration in New Delhi, hoping to gain support from India’s government. However, the government’s response was minimal, according to Sheikh Bashir Shakir of the Imam Khomeini Memorial Trust, a socio-religious organization in Kargil.

“The delaying tactics of the government has emboldened us,” said Shakir. “Our humanism and inclusive approach will hopefully inspire other nonviolent struggles across the world.” 6Ibid.

This article was originally published on Buddhistdoor Global. It is reprinted here with permission.

References

- 1

- 2Religion News Service, In remote Himalayan desert, Buddhists, Muslims, Christians unite to protect land, heritage

- 3Ibid.

- 4Ibid.

- 5Ibid.

- 6Ibid.