The human mind has a strange habit of pretending to itself that the misfortunes that befall others will never befall ourselves. At first glance this is counter-intuitive, for it seems that the instinct for self-preservation should put us on high alert to danger and thereby prepare us to respond. Yet whenever we hear that others have fallen victim to street crimes, burglaries, fatal auto accidents, and terminal illness, a screen drops over our minds that prevents us from acknowledging that the same thing might happen to us. We don’t explicitly deny to ourselves that we are liable to calamity. It’s just that the mind spontaneously filters out information disruptive to our sense of normalcy. To get by in the world, it seems, we can’t allow disturbing news to upset our conviction that events will always move along their accustomed tracks.

Yet if we reflect, we can immediately see that in the time of a fingersnap some unpredictable incident—the sudden death of a loved one, the loss of a job, a disabling injury, a symptom of cancer—may turn our comfortable picture of the world upside down. Just the thinnest veneer of normalcy keeps our lives in balance, and it takes only a flick of fortune’s switch for that veneer to be stripped away, exposing us to the painful bite of reality. To maintain our composure in the face of the unexpected, it’s necessary for us to abandon false comforts and acknowledge our vulnerability, not merely in thought, but with a conviction reaching down to our guts. It is only in this way that we can fortify our minds to withstand sudden shocks and act with wisdom and equanimity.

The same imperatives that apply to our personal dealings with life’s uncertainties can be extended to our response to climate change. The two run along parallel tracks. One conveys us through the upheavals in our private lives with a mind unshaken by sickness, loss and death. The other should convey us through the grim portents of the future and enable us to avert worst-case scenarios. In both spheres, the personal and the collective, we need the courage to see through our illusory sense of security, discern the lurking danger and set about making the transformations needed to reverse the underlying dynamics of disaster.

Though both desire and fear are intended to ward off insecurity and reinforce our everyday picture of the world, ironically they actually achieve the opposite.

In the case of climate disruption, this entails transforming those national policies and global systems that are most responsible for altering our planet’s climate. Such transformations are long overdue. For the past two decades, climate scientists have been telling us that escalating carbon emissions are driving the climate ever closer to dangerous tipping points. Nevertheless, though we hover precariously at the edge of an abyss, we fail to respond with anything close to the haste and scope that the situation demands. Instead, world leaders try to pass the buck for emission cuts to other nations while securing privileges for themselves. On the streets, particularly in the United States, people often react to news of climate change with indifference, a sense of helplessness,or vehement denial. Such reactions are not entirely surprising, considering the volume of disinformation that has appeared in print and over TV, radio and the internet. Members of Congress, with straight faces, have even voted to reject the reality of climate change, doing so at the same time that droughts, floods and wildfires ravage their own states.

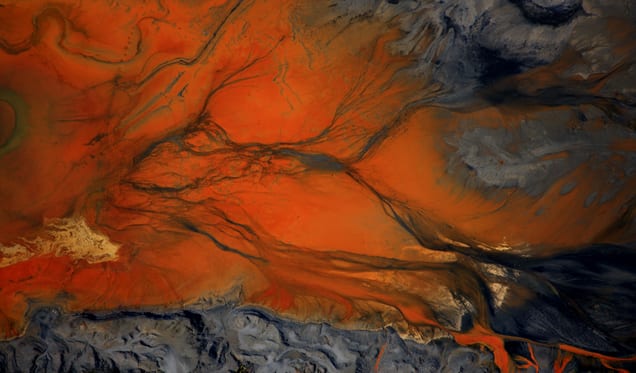

What lies behind this indifference and denial? How do we explain it? When we look at this phenomenon closely, we can see that it is sustained by two primal drives. One is desire or craving, which in this case is the fundamental desire for security, a wish that events will follow their familiar patterns. The other is fear, an instinctive dread of disruption. Beneath our outward self-assurance lies a volatile whirlpool of anxiety, a suppressed concern that things will swerve off-course and confront us with challenges we aren’t equipped to meet. When this anxiety is provoked, it erupts in outbursts of angry denial and denunciation of those who speak plain truth, the arch-enemy of self-deception.

Though both desire and fear are intended to ward off insecurity and reinforce our everyday picture of the world, ironically they actually achieve the opposite. By issuing in denial and indifference, they heighten the insecurity and make us all the more vulnerable to the very disruption that we dread. To stand up to real danger and face it squarely, with wisdom and courage, we must transform desire and fear from causes of mental paralysis into spurs to effective action. This comes about when we marshal their combined forces into a quest for genuine well-being and security. But to transform desire and fear into allies, we sometimes need a rude awakening, an experience that shatters our illusion of normalcy and calls us to the task of wise reflection.

What we need is to feel the sense of urgency collectively, on a mass scale. We must feel it horizontally, as a global community embracing all nations and peoples and life forms on earth, and we must feel it vertically, as directed toward countless generations as yet unborn.

In the texts of early Buddhism, the awakening from complacency is depicted as occurring when we recognize our inescapable vulnerability to loss, illness and death. This radical purging of illusions dispels our unexamined conviction that our physical security is perpetually guaranteed. The tectonic plates beneath our sense of normalcy undergo a seismic shift and can never be restored. In Pali, the language of early Buddhism, the natural response to this shift is called samvega, a word best rendered as “a sense of urgency.” The sense of urgency draws upon desire and fear, but instead of pushing us to run amuck, it instills in us a compelling conviction that we have to do something about our situation, that we have to embark in a new direction profoundly different from everything we’ve tried before.

The Buddha compares the arising of the sense of urgency to a horse’s response to its master’s goad:

Here, an excellent thoroughbred horse acquires a sense of urgency as soon as it sees the shadow of the goad, thinking: ‘What task will my trainer set for me today? What can I do to satisfy him?’ So too, an excellent thoroughbred person hears: ‘In such and such a village or town some woman or man has fallen ill or has died.’ He acquires a sense of urgency and strives carefully. Resolute, he realizes the supreme truth and, having pierced it through with wisdom, he sees it. (Anguttara Nikaya 4:113)

The text goes on to speak of other horses less keen on training, who acquire their samvega, their sense of urgency, only when they feel the goad strike against their skin, their flesh, and their bones. These represent those disciples who, respectively, acquire a sense of urgency when they actually see another person ill or dead, or lose a close relative or friend, or undergo a severe illness themselves.

To deal effectively with the climate crisis, we need to experience a sense of urgency as intense as that which inspires the personal quest for enlightenment. Nevertheless, to mobilize us, this experience must go beyond the sphere of the private and personal. For far too long we’ve been indulging in denial and delay, and the more carbon emissions increase, the harder it will be to emerge intact. What we need is to feel the sense of urgency collectively, on a mass scale. We must feel it horizontally, as a global community embracing all nations and peoples and life forms on earth, and we must feel it vertically, as directed toward countless generations as yet unborn.

Samvega as a response to climate change should become particularly acute when we take into account two facts that grimly stare down at us, casting chilling shadows. The first is the sheer magnitude of what is at stake. Too much is at risk for us to proceed on the hypothesis that climate change might be a false alarm. If we fail to take the momentous steps required of us, we risk losing nothing less than the Earth as we have known it, along with the human civilization that has evolved on its surface over thousands of years. We risk making huge tracts of the planet virtually uninhabitable. We risk condemning small island-nations to rising seas and more violent typhoons. We risk turning verdant land abundant with crops—our grain belts and rice bowls—into barren deserts. We risk mass extinctions, famines, droughts and floods, unpredictable epidemics and large-scale deaths. And we risk kindling more ethnic, religious and cross-border strife, thereby creating more climate refugees, more mass migrations, and more destructive eruptions of terrorism.

While fear over climate disruption often spurs denial and ends in panic or mental paralysis, it may equally well give rise to samvega, a sense of urgency leading to wise decisions to avert the crisis. Everything depends on how we metabolize our fear.

The second factor that should provoke the sense of urgency and raise it exponentially is the recognition that the window of opportunity is closing. We may be about to lose our chance to avert the worst. Since the late 1980s we’ve been told that climate change is a fact; that higher carbon emissions are raising global mean temperatures; that the oceans are undergoing acidification and sea levels are rising; that glaciers are melting and weather patterns are changing; that even the world’s food supply is in jeopardy. Yet world leaders have dithered and procrastinated. They’ve attended conferences and read reports, but at best they’ve taken only tiny steps, token measures that are far from adequate to deal with a problem this severe.

Thus, as the years have slipped by, the amount of carbon in the atmosphere has already passed the 400 parts per million mark and is heading toward 500 ppm. By the end of this century, global temperature is predicted to rise by 4 or even 6 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. We have only 20 or 30 years left to reduce carbon emissions by 80 percent. If we fail to do so, a drastic increase in global temperature will be inevitable, resulting in even more calamities and perhaps the wholesale devastation of human civilization.

Acknowledging imminent climate chaos may initially give rise to fear, but this reaction is not necessarily undesirable. While fear over climate disruption often spurs denial and ends in panic or mental paralysis, it may equally well give rise to samvega, a sense of urgency leading to wise decisions to avert the crisis. Everything depends on how we metabolize our fear. The sense of urgency is, in a way, the wholesome metabolism of fear, transforming our initial disorientation into an intelligent grasp of our situation. Transformed fear thereby becomes the incentive for a genuine solution, opening up a new field of possibilities that can only emerge when we’re moved from the inside out.

When the horse feels the goad striking its back, it knows what it must do: run fast in the direction to which its trainer leads it. When earnest disciples are stirred to a sense of urgency by the encounter with loss and death, they also know what they must do: strive diligently along the path of training and realize the supreme truth. Similarly, when we are stirred to a sense of urgency by destructive climate events, we also know what we must do: reduce carbon emissions as rapidly as possible.

We may be as yet uncertain about the mechanics of emission reductions, but we do understand a few things we must do fast and decisively to avoid wide-scale catastrophe. We must end subsidies to fossil fuel corporations. We must make the polluters pay. We must switch to sources of clean and renewable energy. We must dethrone big money from control over our political system and vote only for candidates who affirm the findings of climate science. We must replace the industrial model of agriculture with a model that gives priority to small-scale producers, end wasteful consumption and learn to live with greater simplicity.

From a broad perspective, we must also envision a new social paradigm that restores true democracy at the national level and establishes a global commonwealth committed to promoting equity for all peoples everywhere. Our collective sense of urgency must be infused with a compassionate concern for all life forms imperiled by the crisis and by a commitment to justice for those who bear the brunt of calamity out of all proportion to their role in causing it.

We are now in a position similar to the thoroughbred horses in the Buddha’s simile. The shadow of the goad was cast 25 years ago, when climate scientists first warned us about the threat of climate change. Since their warnings went unheeded, over the past decade we have felt the touch of the goad against our skin, in the form of more frequent heat waves, droughts, floods, violent hurricanes and wildfires. But still action is being postponed. Perhaps we have not yet felt the impact of the goad against our flesh or against our bones, but if we don’t start moving, the goad will strike. We must act quickly and effectively while we still have a fighting chance. There is no more time for delay.

Join our free, online conversation with Bikkhu Bodhi on November 2 as part of our “Mindfulness and Climate Action” series. Get the full schedule and register here.