Late this past summer I spent a welcome holiday in Shropshire, a land of crags, scarps, and valleys. The geology in this county is, apparently, more diverse than anywhere else of a comparable size in the world: 700 million years of earth history. These lands have given rise to rich mythology; the Long Mynd being compared to a dragon’s spine, the volcano-like Wrekin hill said to be created by a Welsh giant who didn’t like the people of nearby Shrewsbury.

Dukkha has been the flavour of so much of life since March. It’s even multi-layered, like the igneous on top of the red sandstone shaping those Shropshire Hills.

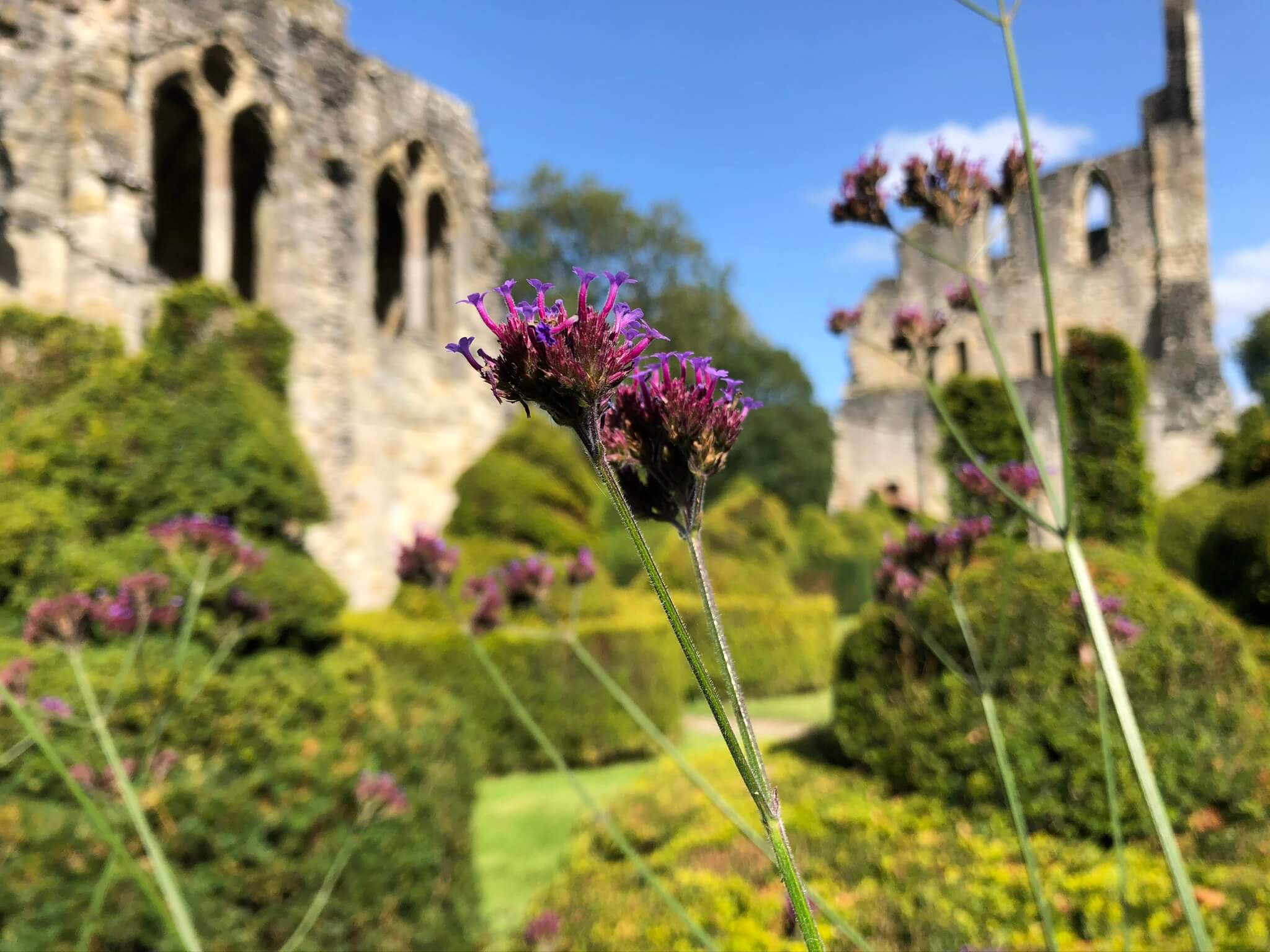

It is a liminal county in that it bridges the man-made border between England and Wales, much disputed over the centuries, as evidenced in the ruins of 32 castles dotted around Offa’s Dyke. Tranquil in the present-day, yet with a quiet tumultuousness of the Church Stretton and Pontesford-Linley fault lines beneath my feet and with tangible reminders of recently warring humans, it was a blissful place to spend a week. The Shropshire Hills aren’t the Rocky Mountains, nor the Alps, but, up close, the inclines are steep and the elements can be full of themselves – the night sky is bright and twinkling, ideal for star-gazing, now fairly rare in the UK.

It was a relief to have a week off, the first since Christmas. I felt extra fortunate to roam this ancient, mythical place with its ambiguous edges and borders, the land somehow defying human categorisation. In a time when life has changed so quickly, become so categorised, along with its clinical words (‘social distancing’, ‘shielding’, ‘self-isolating’, ‘lockdown’), the relief of following my feet felt profound. Coming from a locked down city, my shoulders dropped as I looked around and realised I was, for once, vastly outnumbered by elder deciduous trees and miles of shrubby hedgerow rather than humans.

The week before holidays I’d been reflecting afresh on the three lakshanas, or ‘marks of existence’, one of my favourite Dharma teachings. Sitting and walking on the ancient rocks, those beloved teachings came to life, somehow made visible. Being perched on Shropshire rocks, which used to form the bottom of the ocean bordering present-day South America, reminds me of the first lakshana: anicca, the truth of impermanence, that nothing—absolutely nothing—is fixed or stable. Whether the changes are the bending and stretching of rock happening over millennia, or the four days it took to furlough all my colleagues in my family’s business at the beginning of lockdown, when I felt the shock of going from being part of a viable work community to sitting alone in a Marie-Celeste-like office. Thanks, anicca.

Then I pondered anatta, the second lakshana—the truth that because everything in the universe changes, so too do humans. Who is it, sitting here, typing, anyway? Who was it wondering at that mythical landscape without borders, in the last rays of the late summer sun? Who is she? I realise I have become a bit ‘boxed in’, a bit automaton at times, amplified perhaps by relating to far flung friends, family, clients via the square screen of my laptop. I was further boxing myself in following covid-19 measures, maybe too religiously, even occasionally forgetting to take a daily walk or touching the earth at our community garden because of a hard-to-pin-down fear of facing people, things—myself. In fairness, a shocking family separation in the early days of the pandemic meant that I have been supporting more, feeling protective—a go-to default in my psychic make-up. Go-betweener and protector, they are useful functions, but—note to self—dismantle rather than fortify the castles within, not unlike the ones I explored on those once contested borders.

The preoccupation with covid-19 reporting means that other news is lost. Rising temperatures in the Arctic have shrunk the ice covering the polar ocean to its second-lowest extent in four decades.

And finally, the third lakshana of dukkha, the truth that life is unsatisfactory—and made more unsatisfactory when I forget the first two lakshanas, acting as though I’m here forever and I’m fixed, definite and reliable. Oops. Dukkha has been the flavour of so much of life since March. It’s even multi-layered, like the igneous on top of the red sandstone shaping those Shropshire Hills. I find myself sometimes judgmentally tutting to myself, sometimes in weeping despair, wondering how on earth we will address the climate emergency. Really take in, to our heart of hearts, the devastation of the sixth extinction crisis so love and grief can continue to lead to action, at a time when we can’t resist stock-piling pasta and toilet roll. It’s not the whole story. In other moments I am bowled over by the ordinary acts of kindness and the strengthening of community in our street.

Dukkha has been highlighted during the pandemic. I remember the days during the ‘first wave’, enjoying the peace of our small garden with so little traffic on the roads and so much birdsong, before the peace was broken by a passing ambulance—we live equidistant from two emergency rooms. The dukkha of systematic inequality is highlighted in who is most detrimentally affected by COVID-19. Following government advice to ‘stay home and save lives’, more of us than ever were online and witnessed the murder of George Floyd—his untimely death touching those who mightn’t have otherwise been touched. Two weeks later here in Bristol the statue of Edward Colston—a wealthy slave trader—was, at long last, mobbed and chucked in the river in #BlackLivesMatter protests, reflecting the potency of our digitally connected and interconnected world.

The spirit of those ancient Shropshire hills, those starry nights and the early autumn mist covering the valley’s floors, stay with me as I carry on ‘unboxing’, trying to stay open to everything that is changing. Where do we go as we un-lockdown, in this strange twilight of infection rates climbing, and the quiet dread of waiting for the death rates to climb, too? The preoccupation with covid-19 reporting means that other news is lost. Rising temperatures in the Arctic have shrunk the ice covering the polar ocean to its second-lowest extent in four decades. In a very not-in-the-moment way, I find myself drifting ahead, a year, three years, 10 years, 50 years from now. As we learn to live longer-term alongside covid-19—keen to multiply itself, as are we—what do I/we learn about how we relate to ourselves and others? Will the sudden life changes make me more flexible, more adaptable, or more fearful of surrendering me-making? Thinking of the Arctic, of George Floyd, so many others, how will we/I remember the importance of the lives of all that lives, human and other-than-human and more-than-human life, beyond the fallacy of me and mine, the illusion of separation and permanence? What am I learning about Dharma practice? How do I keep on engaging, keep on stepping down from my meditation cushion with each new breath?

As I re-engage with life in the four walls of a busy city, I find myself spontaneously bringing the elements to mind as I gather to sit. I’m not doing a full-blown version of the traditional Tibetan practice of recollecting the six elements as I have in the past, yet I find it helpful to bring each of the elements to mind: earth, water, fire, air, space, consciousness. I sense each one—its nature and textures—within and far beyond me, whether that’s imagining the solidity of the earthy ridge of Wenlock Edge, back in the Shropshire Hills, and then sensing the strength of my earthy bones, contrasting with their flesh covering. This earth, and water, and fire, and air, and space, and consciousness, it is not me, it is not mine. Recalling and reflecting on the elements I uncover a simple peace and a boundless love. Peace in the poignant knowledge of the fleetingness of life in this skin, and noticing that even 700 million year old rocks are still moving and shaping.

One Response

Thank you Emma, your reflections really spoke to me today. Acknowledging the eons of planetary change, the humans and natural forces that have shaped our present day landscape, is so grounding and reverential…it brings gratitude from all angles.

The Tibetan practice of recollecting the six elements is new to me, so i am going to head off down that rabbit hole now…of particular interest as i am also investigating the Ayurvedic notion of the elements that make up our bodies and behaviours…there is no getting away from these building blocks of all life!