As more Buddhist teachers begin to embrace ecoDharma as part of their mission, so too are increasing numbers of environmental activists embracing aspects of the Buddhadharma, such as mindfulness, as part of their skill sets. Sometimes, as in the case of Tim Ream, there’s a sweet spot where Buddhist practice and environmental activism bring new approaches to both realms.

I recently chatted with Tim about his work.

Tim is a teacher at the San Francisco Zen Center and his practice extends back decades. He has also offered ecoDharma workshops through One Earth Sangha and the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. But his journey to ecoDharma began decades before that. You can learn more about his early work from the 1999 anti-logging documentary Pickaxe, linked on his website. As an environmental activist, Tim worked as a lawyer on such causes as the “Keep It in the Ground” campaign, and lawsuits in the western United States, to prevent leasing of public lands for fossil fuel extraction, an anti-fracking initiative in New Mexico, wildlife protection lawsuits in Oregon, and a stint with the US Environmental Protection Agency.

… the path of fighting was eating me up in an unsustainable way.

Ultimately, however, he came to feel that his efforts at the EPA were severely hampered by the protracted and uncertain process of litigation by stakeholders, including environmentalists, industry, and sometimes both, not to mention the fact that the EPA’s mandate is ultimately dictated by Congress. As he describes it:

I admire folks who can stay in the legal fight for the Earth across decades. The same goes for frontline activists. They are doing critical work and our world would be much, much darker without them. But fight they do, and practically non-stop. By the time I went to law school, I’d already been fighting for many years. It’s tough to always be fighting and to be surrounded by professional fighters. That was the time of my life I strayed furthest from Zen practice and it became clear that the path of fighting was eating me up in an unsustainable way.

Delving deeper into Buddhist teachings of interdependence, Tim came to believe that there is:

. . . only one universal prescription—people need to relearn to love the Earth. That usually first means loving a tiny part of it: a nearby forest, or a river, or a coastline, or old oaks, or wolves, or yellow warblers. And then ever deepening that love. People only defend what they love and nobody really can say they love the preindustrial climate. They love places, and plants, and animals. Practice can open hearts to loving Earth, especially when teachers point in that direction. And people who deeply love the Earth will always be the best Earth defenders.

Impetus for change in the world of environmental activism often comes from below. “That is very hard to do in many Dharma centers. Sanghas can be quite hierarchical and even authoritarian. Bigger ones present layers of bureaucracy. Power is often held by a few and those few are often older and more conservative.” His prescription:

Activism is needed within the Dharma center to shine light on ecological shortcomings, but guess how well that goes over, especially when the pressure comes from young newcomers. Still, students need to keep talking about what is important to them. If their cries continue to go unheard, maybe it is time for a new teacher.

This is not an easy path. Acknowledging that Buddhism as transmitted in the West over the past decades has focused too much on personal transformation, and understanding how that came to be, Tim hopes we can go beyond that now. He’s optimistic about the congruency between stable Buddhist practice and addressing the suffering of the world outside our practice centers.

I expect the Dharma that will be taught in 30 years [will be] a lot different from what was taught 30 years ago. Just in my 30 years at one or two practice centers, I can see a deepening of maturity in the teachings and the practice. A more solid foundation can breed more creativity. I believe the leaders of our centers these days will keep finding more eco in their Dharma.

Tackling the complementary challenge of alleviating burnout in eco-activists, Tim helped to create a workshop that might be of great interest to many folks working in Earth-activist roles and related work. It is a reworking of a course offered by the Search Inside Yourself Leadership Institute, but targeted for Earth-activist types. The premise is that the most important quality lacking among environmental leaders today is compassion, that the way to build more compassion is through increased emotional intelligence, and the critical building block of emotional intelligence is mindfulness. The course is very practical and non-religious—it’s about how to build a mindfulness practice right in a work setting and is great for both individuals and teams. There are live and online versions.

Over the next year, he’ll also be co-leading a fully funded and fully legal psilocybin therapy retreat for Earth-activists. I’m seeing increasing work in the field of climate psychotherapy, and perhaps this will prove to be a valuable addition to the genre. He tells me he’ll also be doing some contract work for a variety of environmental organizations.

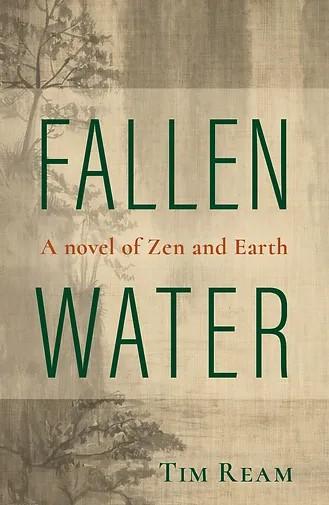

However, getting back to the matter of nurturing people’s love for the Earth, Tim’s most recent work has been writing an ecoDharma novel, Fallen Water, set in a rural California Zen center. It’s billed as taking place at the intersection of Zen practice and Earth-activism. Published in March 2024, it is awesome. You can find out more about the book on his website, and from the Buddhist Fiction blog, where there’s a five-star review—by me, full disclosure.

Students need to keep talking about what is important to them. If their cries continue to go unheard, maybe it is time for a new teacher.

When I asked Tim about why he wrote the novel, we talked again about how learning to love the Earth is about cultivating compassion. The classic “turning about in the mind” of Zen enlightenment cannot be inculcated through scientific evidence or intellectual means but it can be inspired by narratives. As we know, fiction and nonfiction reach us through entirely different cognitive pathways. Fiction incorporates the dimension of empathy. Recalling his first introduction to Zen years ago, through the anecdotes in Paul Reps’ book Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, he remembered wanting to be like those Zen Ancestors. Presenting ecoDharma in a novel reaches an entirely different audience from those who would typically be reading a book about Zen, a book about environmental activism, or a legal brief about a policy position. Like Paul Reps’ book, it’s about people. That’s a good thing!

If you want to understand what the future of ecoDharma might look like in North America, Tim Ream offers a glimpse of where this emerging Dharma door might lead.

This article was originally published on Buddhistdoor Global. It is reprinted here with permission. John Negru’s Ecodharma series can be found here.

Tim Ream is a long-time Earth activist and Soto Zen practitioner. He received lay ordination from Tenshin Reb Anderson in 1994 and has engaged since in repeated, intensive residential practice, mostly at Tassajara Zen Mountain Center and Green Gulch Farm. Tim is an organizer, campaigner, writer, and environmental attorney. His activism ranges from direct action and civil disobedience like tree-sitting and road blockading to successful lawsuits to protect wolves and other species. He is the author of Fallen Water: A novel of Zen and Earth.