Longtime environmental scholar and writer Stephanie Kaza’s latest book Green Buddhism is a rich resource for Buddhists trying to address the environmental crisis, indeed for anyone interested in the intersection of Buddhism and environmentalism. The book brings together 21 essays spanning 25 years of Kaza’s remarkable career combining Buddhist practice with activism and scholarship: from learning meditation and Buddhist creativity with Chogyam Trungpa, Allen Ginsberg, and Philip Glass at Naropa to Zen practice at the Santa Cruz and Green Gulch Zen Centers; organizing work with the Buddhist Peace Fellowship; and serving as education director of the UC Berkeley Botanic Garden and faculty member of the Environmental Program at the University of Vermont. Throughout, she has studied with a panoply of influential Buddhist teachers—Kobun Chino Otogawa, Thích Nhất Hạnh, Jack Kornfield, Norman Fischer, Joanna Macy, Robert Aitken, Rita Gross, Blanche Hartman, among others.

“It seems like an indulgence to take the time to cultivate mindfulness when so much is being lost. But this is the tension – to find a considered way of acting not based on reaction.”

The book begins with a section titled Intimate Relations and includes Kaza’s exploration of conditioned mind versus attentive mind and direct experience, and the “desire to fully meet others as complete beings” without the conditioning of self. Here, she masterfully conveys some of Buddhism and ecology’s most sublime thoughts, drawing on 12th century Zen master Honghzi’s poetic description of the “field of bright spirit” to describe the “unified field of energetic flux out of which all forms arise.”

Envisioning Green Buddhism

In the second section of the book, Envisioning Green Buddhism, Kaza profiles leading green Buddhist thinkers John Daido Loori and Joanna Macy and offers her vision of the “green practice path and possibilities for deepening green Buddhist practices in community.” In one chapter she discusses the importance of mindfulness in environmental activism: “It seems like an indulgence to take the time to cultivate mindfulness when so much is being lost. But this is the tension – to find a considered way of acting not based on reaction.” It is an important message to remember for anyone involved in a climate march or other mass environmental action, which often involves shouting and tense emotions.

Another chapter focuses on applying mindfulness to consumerism, as an examination of consumerism is at the heart of any serious environmental practice.

If our spiritual goal is to reduce harm in the world, we must ask such hard questions as: What do I actually need? What is my fair share? How do my choices impact others?….The point is to contemplate these hard questions with full attention and see where they lead you…

They lead Kaza to suggest launching a Buddhist consumer-activism movement, with Buddhist centers “modeling the reduction of consumption, promoting a lifestyle based on simplicity and restraint.”

Acting with Compassion

In part 3 of the book, Acting with Compassion, Kaza looks at the “interdependent concerns of green Buddhism, ecology, and feminism” and identifies three contributions Buddhist teachings can make to the climate conversation: exposing dualistic thinking; developing a Buddhist climate ethic; and building capacity for resilience.

“The environmentalist can be perpetually anxious and out of touch with sustaining sources of joy. In the face of unending challenges this is not a recipe for stability or equanimity.”

Dualistic thinking makes it easier for people in the West to ignore the problems of the climate have-nots in poor countries such as Bangladesh. Buddhists can help break down such thinking with continued reflection on the interdependence of self and other, and the core practice of self-reflection as part of action. Buddhism’s nondualistic view of reality also encourages acting from an inclusive standpoint, not the us-versus-them stance that’s common in environmental battles, based on the Western emphasis on individualism. Kaza writes, “It is the inflated idea of the self as one’s central identity that blocks collaboration.”

Nonharming is the central tenet of a Buddhist climate ethic. In the simple and eloquent words of Cambodian Buddhist teacher Ghasananda: “If we protect the world, we protect ourselves. If we harm the world, we harm ourselves. We are in the same boat. Therefore, we must take care of the boat.” After all, Kaza writes, the nonharming that Buddhism teaches applies to humans, places and the beings within the places.

Indra’s Net

Kaza addresses the very real fear many of us feel that our individual efforts are tiny and futile in the face of the overwhelming problems of the climate crisis. Our individual efforts do matter, and our group efforts matter even more, she says. “Green Buddhist practices are a part of this ethical effort to build a more mindful, stable, sustainable, and peaceful society,” Kaza writes. “This is certainly a tall order, but every action in this direction counts, and all of it helps stem the frightening tide of planetary destruction.”

Dualistic thinking makes it easier for people in the West to ignore the problems of the climate have-nots.

In regard to resilience, while Green Buddhism is not overtly an activist’s handbook, Kaza encourages us to look at our own attitudes and practices as activists. In the chapter “Practicing with Greed,” she writes of the need to examine greed, not to banish it, and shows how investigating it can be fruitful. She talks about the “greed” of some on the environmental path for more time, more knowledge, more citizen engagement, more status and more power to “take all the actions we see as necessary to save the ailing planet.” These are wise actions in service of a wholesome aspiration. But, Kaza writes, “Caught in a cycle of greed for time, the environmentalist can be perpetually anxious and out of touch with sustaining sources of joy (such as fresh strawberries). In the face of unending challenges this is not a recipe for stability or equanimity.” Thus, again, the value of bringing mindfulness and non-attachment to climate action.

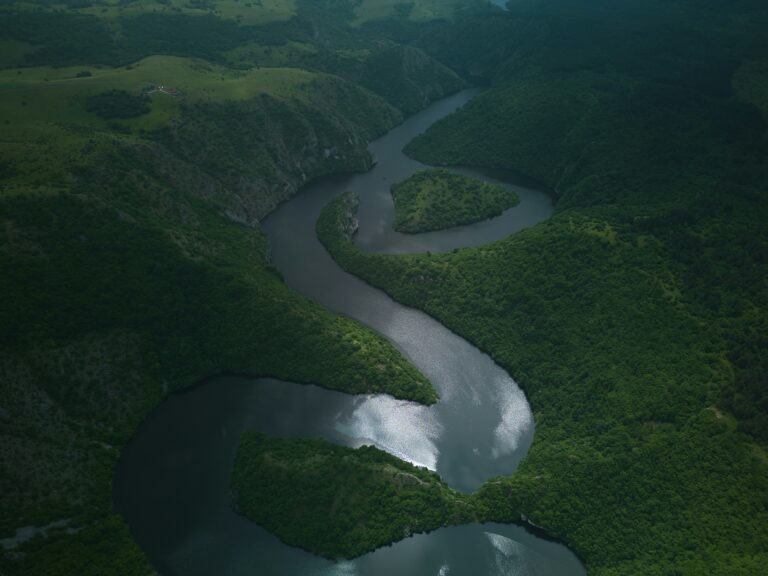

Because these writings are collected from Kaza’s work over many years, some themes – the importance of nondualistic thinking and of interdependence – come up again and again, reminders of their importance. If there is one unifying theme in the book, it may be that of interconnectedness. Kaza explores the vivid metaphor for interdependence of Indra’s net, which

consists of an infinite number of crisscrossing nets, with a jewel at every point of intersection. Each jewel has an infinite number of facets that reflect every other jewel in the net…. There is nothing outside the net and nothing that does not reverberate its presence throughout the net. The image [conveys] the interdependent nature of reality, infinitely linked in relationship and infinitely co-creating every being.

In a section on relational ethics, Kaza writes:

The aspiring bodhisattva encourages the practice of compassion as a means of establishing a profound sense of interrelatedness. This is what allows us to feel the connections with disturbed ecosystems and threatened species, distressing as they may be. Sensitivity and moral concern can extend to plants, animals, forests, clouds, stones, and sacred places. Buddhist relational ethics are based on knowing that one cannot act without affecting other living beings, that it is impossible to live outside the web of interconnectedness.